More than anything else, Robert Bloch’s career is a testament to perseverance. His autobiography, along with the numerous mini-bios and write-ups about him that populate the internet, are testaments to the fact that writers are workers, no exception. And a lesser worker than Bloch would’ve been put off from the film industry long before Great Britain’s Amicus Productions came calling in the mid-1960s.

Back before his figurative jump across the Pond, Bloch had been involved in some sub-par stinkers. His first two film experiences, The Couch and The Cabinet of Caligari (a remake of the German silent classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), had earned him mostly white hairs. The writing process for both films had been dreadful, with Bloch on the receiving end of directorial and studio demands that tried to either squeeze him out of the writing credit or discard his script altogether. Years later, when addressing these films along with a 1966 botch called The Deadly Bees, Bloch admitted that: “I shudder every time this item [The Deadly Bees] is mentioned or shown.”

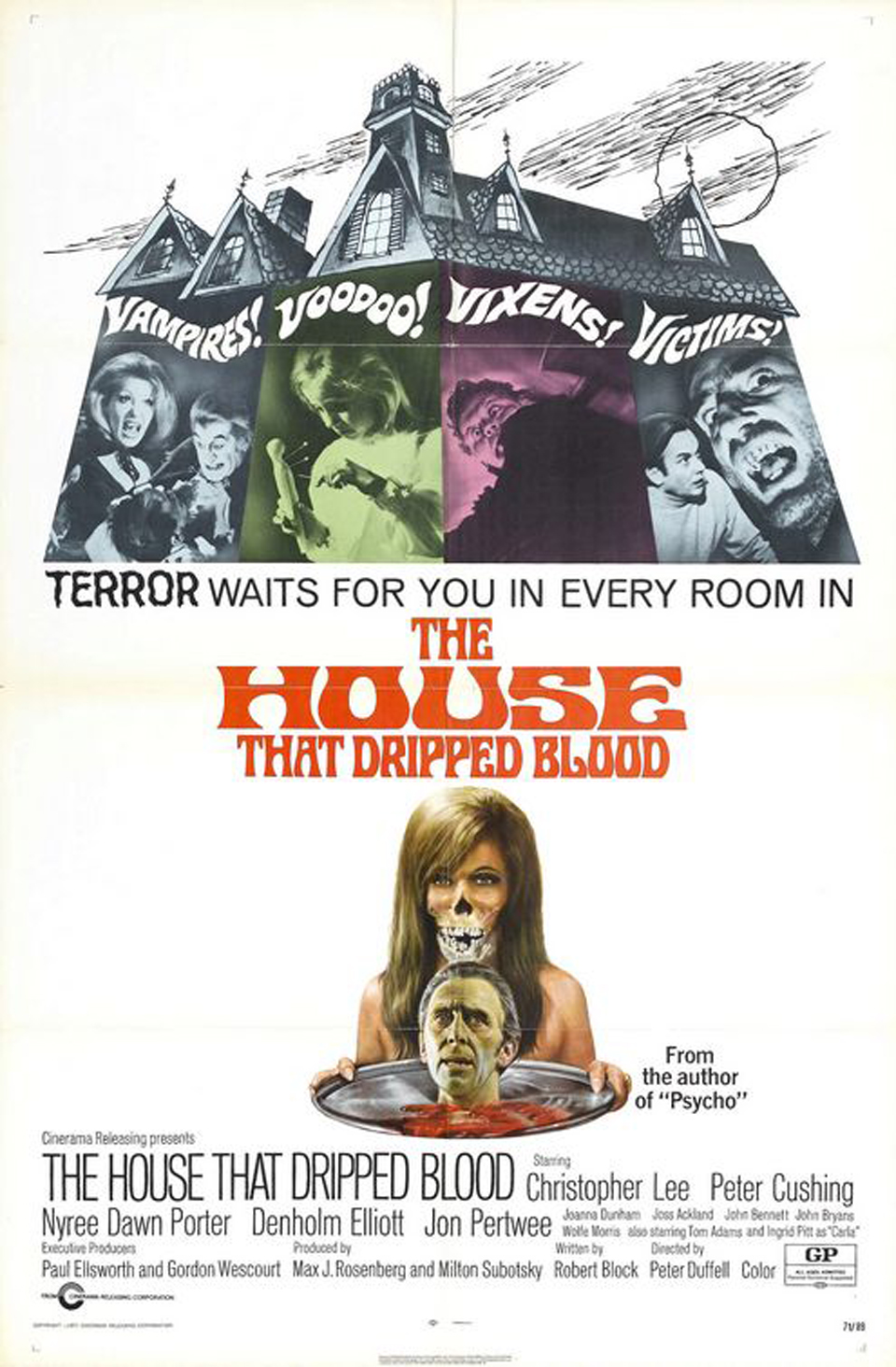

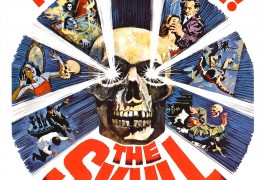

Thankfully for Bloch, television work kept him busy, plus two films from 1964—Strait-Jacket and The Night Walker—proved to be decent examples of Bloch’s unique genius for taut psychological tales. Then, one year later, Bloch’s name was associated with two horror film icons that had earlier helped to revitalize and even revolutionize the genre in the late 1950s with a series of updates on the classic American monster movies from the 1930s. These two men were the actors Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, and along with the director Freddie Francis, they made The Skull for Amicus, a direct competitor with Hammer, their other place of employment, in 1965. The Skull would prove to be the first in a series of Bloch-themed films made by Amicus, most of which Bloch wrote himself. For a brief period, these films helped to establish not only Bloch as one of the primary purveyors of high-quality horror, but they also offered the world a new breed of horror film – the horror anthology.

- The Skull

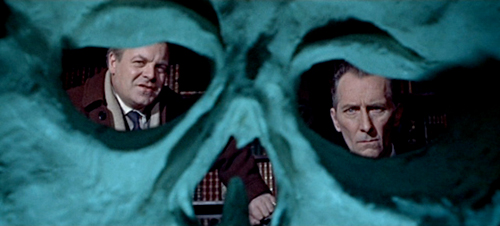

Including The Skull in an article ostensibly about Robert Bloch’s screenplays is a bit of a deceit. You see, Bloch did not in fact write the screenplay for the film. That honor belonged to Milton Subotsky, the American-born producer who, along with fellow expat and native New Yorker Max J. Rosenberg, founded Amicus Productions. Once filming began though, the script was drastically rewritten by Francis. Bloch’s involvement with the film began and ended with his 1945 short story “The Skull of the Marquis de Sade,” which had originally been published in Weird Tales. In trying to compete with Hammer, whose success Subotsky and Rosenberg were trying to emulate, Amicus wanted desperately to somehow tie their brand in with that of the man who had written Psycho. This is probably the major reason why The Skull was chosen as Amicus’s second horror picture overall, and according to most critics and regular folks who’ve seen film, Subotsky and Rosenberg hit a run home, or at least a triple with their sophomore effort.

Although more scattered and lot less sardonic than Bloch’s original story, The Skull nevertheless successfully manages to pull off the tale of poor Christopher Maitland (played by Cushing) and his unfortunate purchase of the skull of the infamous Marquis de Sade. In history, de Sade was a debauched French aristocrat and a libertine who believed in complete, unadulterated freedom. What this translated to was orgies, filth recorded for posterity, pornography masquerading as philosophy, and generally poor hygiene. The apotheosis of de Sade’s literary assault on good manners was his 1785 novel The 120 Days of Sodom, which sat unpublished until the relatively more open-minded 20th century (1905 to be exact). A tale about four wealthy ne’er-do-wells who agree to experience sexual gratification at the cost of torture and kidnapping, 120 Days of Sodom has been banned by numerous governments and served as the groundwork for what has been called the most controversial film of all time—Pier Paolo Pasolini’s anti-Fascist art film Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom.

Obviously, a man responsible for such work would not go without notice. Eventually, de Sade was arrested by Napoleon and for the remainder of his life he languished in prison, then later an asylum after his family had him declared insane. After death, de Sade’s skull was unearthed by phrenologists who wanted to see if the man who lent his name to the word “sadism” left behind evidence of his madness in the very structure that housed his diseased brain. The Skull begins at this exact moment, with Pierre (played by Maurice Good) taking the famous noggin back to his home laboratory. Pierre soon becomes engrossed in the work, even to the point where he shrugs off the sexual advances of a handsome young lover (played by April Olrich). Not to be deterred, the woman takes up watch on Pierre’s bed in order to ensnare her lover before the night is over.

Unfortunately for her, when Pierre attempts to boil the flesh away from the skull, he is met with a presumably grisly off-camera death.

Cut to modern-day London. Maitland, an expert on the occult and a collector of rare artifacts, is in a bidding war with Sir Matthew Phillips (played by Lee). The items that the two sweat over the most are a set of grotesque stone figures from the 17th century, all of which represent the chief demons of Hell. Sir Matthew ultimately wins the four figures with a steel concentration that borders on the unnatural. When Maitland asks why he wanted the figures so badly, Sir Matthew can only reply: “I don’t know. I really don’t know.”

After his defeat at the auction block, Maitland returns to his shady fence/buyer Anthony Marco (played excellently by Patrick Wymark), a snuff-sniffing roustabout who lives in a greasy flat full of antique items that may or may not be stolen. Having whetted Maitland’s appetite with a volume bound in human skin, Marco asks Maitland if he’d be interested in a much more expensive item—the skull of the Marquis de Sade. During Marco’s attempted sale, he relates how the skull has a history of forcing people to commit heinous crimes, and even more startling is Marco’s willingness to haggle on the price.

Marco has a reason for such a ludicrously unusual business decision: he, or one of his lowlife friends, stole the skull from Sir Matthew. When Maitland tells Sir Matthew about Marco’s offer over a friendly game of billiards, Sir Matthew tells him of the robbery and confesses that he’s glad to be rid of the thing. The skull is possessed by a demon or demons, Sir Matthew tells Maitland. These invisible beings inside of the skull have followers too, and to make matters worse the skull has a will of its own. A very, very strong will that can make even the most cocksure bend before it. Sir Matthew barely escaped with his sanity, and he warns Maitland to avoid the skull at all costs.

Sir Matthew’s story, along with his confession that he purchased the figurines because the skull, which wants them for its blasphemous ceremonies, forced him to, only peaks Maitland’s interest. That night, as Maitland sits reading the book that he bought from Marco, he’s visited by the skull’s agents in a surreal dream that has Maitland being tortured by demonic policemen and a judge who forces him to play Russian roulette. This is the skull’s way of calling out to Maitland, who soon finds himself in Marco’s apartment, with the latter dead as the result of some vicious mauling. After the police and the coroner leave the scene, Maitland returns to the flat in order to steal the skull. While in the process of the theft, Maitland accidentally kills Marco’s nosey landlord by pushing him down several flights of stairs.

After this crime, Maitland takes the skull home and places it in a glass display case in his study. Within hours, Maitland sets up a ceremony with black candles and a pentagram in order to communicate with the detached head. As he watches the skull remove itself from its enclosure and float down towards him, Maitland finally realizes just how evil the skull really is. After it tries to get him to murder his wife, Maitland wraps a crucifix around the glass case’s handles. No dice; the skull breaks out anyway and deals with Maitland.

Despite its clear intentions (i.e., “hey, let’s make a Hammer picture without actually being Hammer Studios”), The Skull is a well-produced and well-shot film with excellent coloring and wonderful cinematography. Freddie Francis, a cinematographer who fell into directing just as Hammer, his original home, was coming into its own in the mid ‘60s, did an exceptional job. The Skull displays a cinematographer’s eye, especially during the great shots when we see the action through de Sade’s boney and empty eyes. Another great shot comes near the end, when the detached head floats around Maitland’s darkened house in search of its newest owner.

Besides great work from Cushing, Wymark, and Francis (Lee’s role is far too minor), the other noticeable achievement in The Skull is its music, which was done by the avant-garde composer Elisabeth Lutyens. Unlike her more unsettling solo pieces, Lutyens compositions on The Skull ring with the familiar bombast of Hammer regular James Bernard, although certain moments are more, shall we say, Schoenbergian than anything Bernard ever produced.

- Anthologies from Hell, Part One: The Torture Garden

The Skull did well enough upon release that Bloch soon found a job writing scripts for Amicus, who were starting to pick up momentum just as Hammer was losing some steam. But, as with his last time out in the picture business, Bloch got off to an inauspicious start with the British company. His first original screenplay for Amicus was for The Psychopath, which was also directed by Francis and released in 1966. A very hard to find film these days, The Psychopath is one-part a British knockoff of the West German krimi films (which were either loosely based on or simply influenced by the British crime writer Edgar Wallace) and one-part early giallo without either the Italian love of explicit sex or violence. The Psychopath deals with a serial killer from a German family with a dark secret. The killer, who seems modeled somewhat after the then very recent Jack the Stripper slayings (which still remain unsolved), has as his calling card a set of dolls, which he leaves behind at every crime scene. An early serial killer film that shows the influence of Mario Bava, The Psychopath is mostly notable because of its tagline: “Mother, may I go out to kill?” In 1982, the New Jersey punk band The Misfits would later rework this into a song called “Mommy, Can I Go Out & Kill Tonight?”

While The Psychopath ultimately did well in Europe, Bloch’s next screenplay—the horribly-titled The Deadly Bees—did well with nobody. Once featured in an episode of Mystery Science Theater, The Deadly Bees should have been a much better film. Bases on a mystery novel by H.F. (Gerald) Heard called A Taste for Honey, The Deadly Bees saw Bloch once again cast in the role of overlooked and trivialized author.

The Deadly Bees began to fall apart even before filming. According to Bloch’s own autobiography, his script had been explicitly written for Christopher Lee and Boris Karloff, who had played the detective character Mr. Mycroft in an earlier adaptation of the novel for television. Amicus decided that the two were too expensive, plus scheduling conflicts rendered them unavailable anyway.

The next stab came from Francis, who once again signed on to direct a Bloch script. Francis, along with a writer named Anthony Marriott, decided to rewrite Bloch’s script to the point of extinction. What Francis filmed bore little resemblance to Bloch’s original screenplay, from the exclusion of the Mycroft character (a deletion that the studio demanded) to the complete muddying of the novel’s storyline. What emerged after tight schedules and enormous salaries forced the project and its script to fall on the shoulders of Francis is the cinematic equivalent of weeks-old borscht. Filled with uninspired performances, a hooky plot, and thoroughly unlikeable people, The Deadly Bees went, in the words of Bloch himself, “unwept, unhonoured [sic], and unstung.” The film does have one bright spot in the form of a very young Ronnie Wood, who can be seen playing with a fictional rock band during one of the film’s early scenes.

After the fiasco of The Deadly Bees, Bloch and Francis were surprisingly paired once again for the 1967 film The Torture Garden. An early example of Subotsky’s beloved “portmanteau” films, The Torture Garden presents an omnibus of four separate stories that are each grounded by a framing narrative. In the framing narrative, five people decide to pay a little extra in order to see truly frightening things at a sideshow attraction. The show’s leader is Dr. Diablo (played by Burgess Meredith), an aptly named hawker who, as the film progresses, seems to act more and more like his sinister monicker. Dr. Diablo promises his brave participants that they will experience inner fear when they look into the “shears of fate,” which are controlled by a fortune telling automaton (played by Clytie Jessop) that is in actuality the Greek goddess Atropos, one of the three Fates. Diablo promises his patrons that what they’ll see is their future, and since The Torture Garden is a horror film, you can bet none of these futures are brighter than pitch. And as it turns out, Dr. Diablo isn’t just interested in moral lessons, either. After each story comes and goes, Diablo reiterates the power of fear and then just asks for the next person up. There is little repenting in The Torture Garden, and one gets the idea that the film actually takes place in Hell and each character is one of the already damned. The ending, which has Meredith looking directly at the audience with horns, a black goatee, and a pit of fire playing underneath him, lends some credence to this interpretation.

All four episodes in The Torture Garden are based on earlier short stories by Bloch, some of which were already quite old by that point. The first one, which is simply entitled “Enoch,” deals with Colin Williams (played by Michael Bryant), a greedy heir who would rather force his dying uncle (played by Maurice Denham), a local miser known for paying for his groceries with gold coins, into an early grave than actually work. When Colin withholds his uncle’s medicine in order to find the location of his secret treasure, the old man kicks the bucket and Colin is left alone and still broke. His luck momentarily changes however when he follows a trap door down to the house’s basement. Underneath the debris is a coffin, which the viewers are led to believe contains the remains of the house’s older tenant – a witch who was reported to have had well-stocked coffers.

When Colin opens the lid, a dirty cat leaps out. In its wake is a headless skeleton with greenish blue liquid bubbling from its neck wound. It turns out that the cat is actually Balthazar, a demonic familiar who has a hunger for human heads. Balthazar telepathically tells Colin that he once served his uncle before he was buried away in the coffin. In return for feeding him fresh corpses, Balthazar promises to tell Colin where the gold is hidden.

Colin does eventually find the lucre, but the price proves too high. The body count piles up and Colin finds himself locked away because the police have found what he did to his uncle’s former nurse Parker (played by Catherine Finn). But prison proves no barrier for a cat, and the story ends gruesomely.

The middle section of The Torture Garden is its weakest spot. The two tales – “Terror Over Hollywood” and “Mr. Steinway” – are more or less ruminations on success and the cost that comes with either trying to achieve it or protect it. In “Terror Over Hollywood,” which updates horror’s long fascination with immortality for a more technological age, the aspiring actress Carla Hayes (played by Beverly Adams) first tricks her way into a dinner date with a producer by intentionally burning her roommate’s dress with an iron, then winds up witnessing the murder of the famous Hollywood actor Bruce Benton (played by a suave Robert Hutton). Even though a gangster’s bullet lodged itself very visibly inside of his skull, Benton still manages to show up to work after a short spell with the private surgeon Dr. Heim (played by Bernard Kay). Perturbed by this improbable comeback, Carla’s inquiries soon led to a discovery that proves that those who stay on top for long are anything but human.

In “Mr. Steinway,” a grand piano with the name Euterpe (which is yet another reference to Greek mythology, with Euterpe being one of the Muses most often associated with music) proves protective of the talents of Leo Winston (played by John Standing), a famous concert pianist. Initially tasked with interviewing Leo for her magazine, Dorothy Endicott (played by Barbara Ewing) very quickly falls in love with the handsome musician. Before long the pair are spending most of their time together. Much too much time, Euterpe believes. A seeming cross between a jilted goddess and the spirit of Leo’s dead mother, Euterpe finds a very extreme way of disconnecting the young lovers from one another.

The weakest story of the bunch, “Mr. Steinway” presents a cast full of boring people. From the fey momma’s boy to the overly possessive girlfriend who seems more in love with luxury than anything else, “Mr. Steinway” is in fact a microcosm of what makes The Torture Garden middling. With the exception of the final story, The Torture Garden presents three tales that water down the Bloch originals. Partially an issue of brevity and partially the result of having a carinvalesque framing narrative (which gives everything thing a campy, rather than a scary edge), The Torture Garden is more of a morality play than a fully-developed story. That said, the film’s final moment, which is a short tale called “The Man Who Collected Poe,” is more than worth the wait.

Featuring Jack Palance and Peter Cushing, “The Man Who Collected Poe” is a ghoulish little number that poses the question: what if Edgar Allan Poe were still alive? Palance’s Ronald Wyatt, a wiry, nervous man who seems always in the middle of lighting his pipe, finds out the answer to this question in the Maryland home of Lancelot Canning (Cushing), the world’s foremost collector of all things Poe. After being invited to Canning’s home, Wyatt and Canning spend a drunken evening together which includes the type of Poe memorabilia and artifacts that most universities would kill for. Chief among these finds is an archive of Poe’s unpublished stories, which Canning keeps in his cellar. Amazingly, Wyatt notices that the manuscripts bear the watermarks of contemporary paper companies, an impossibility if Poe had written them before his death in 1849. A door in the cellar, which leads further into Canning’s most secret collection, reveals the truth about the manuscripts.

What makes “The Man Who Collected Poe” so memorable in The Torture Garden is Palance’s performance. Besides Palance’s accent (which slips and slides between American and vaguely English) and Cushing doing a rare on-screen take as a drunk, the thing that sticks with viewers is Palance’s lear, his frozen, artificial smile, and his bouts of uncomfortable laughter. In short, Palance plays the film’s true kook and is much more powerful than either the hammy Meredith or the typically understated Cushing. It’s no wonder then that it’s Wyatt, the patron who tries to make a deal with the devil twice, who leaves the screen with any real fanfare.

To Be Continued….