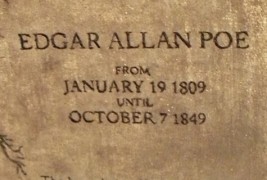

Even in Baltimore, as history-drenched a city as you’ll find in the United States, Edgar Allan Poe stands out as a favored son. He was by birth a Bostonian, and lived for a time in both Virginia and New York, but Baltimore has claimed him. In school, Halloween meant an inevitable reading of “The Raven” or “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Every January 19th, the news reported on the mysterious, black-clad figure who offered a graveside birthday toast to Poe with cognac and roses. And when Baltimore finally got another football team, they named it the Ravens.

I read Tales of Mystery and Terror when I was in sixth grade. My parents bought me a Penguin Classics paperback edition of it for my twelfth birthday. I remember a lot of winter mornings on the school bus reading that book. Winter in Maryland is the perfect season for Poe. For one thing, it’s not really winter, but an even bleaker, muddier fall. Riding across bridges, I could look down into gorges filled with bare trees and dried rivers. Old railroad tracks stood crumbling and covered in dead ivy. The sky was a shade of gray so intense it hurt your eyes to look at. For me, horror country isn’t New England hills or Southern bayous, but those deep Maryland canyons filled with bare trees.

Sadly, Ravenous Monster wasn’t around for Poe’s bicentennial, but we are here, fortuitously, for his two hundred and second birthday. It wasn’t until I heard that it’s been two-hundred and two years since Edgar Allan Poe was born that I realized it’s been at least a decade since I read anything by him. For a Marylander, that’s a bit contemptible. For a horror writer, that’s downright shameful.

The Penguin Classics paperback my parents bought me disappeared in one of our many moves, but a few years ago my sister bought me a nice, leather-bound edition of The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe with faux gold-leaf pages and a ribbon bookmark. One dark midnight, with two hundred and two years of Poe looming over me, I took a very dark trip down the raven-haunted woods of memory lane.

I. “The Tell-Tale Heart”

I was planning on skipping “The Tell-Tale Heart,” but it was my introduction to Poe—by way of a Great Classics Illustrated book read to me by a babysitter named Lori. The story was abridged, but Lori was an art student, and she delivered the “Why will you call me mad?” line with all the gothic drama it deserves. I was totally sold. I hadn’t even liked scary stories before, but I was drawn in by that sick little tale about guilt, murder, and Madness with a capital “M.”

In eighth grade, while tutoring some inner-city Baltimore kids on the anatomy of the human heart, I managed to convince their teacher to let me read “The Tell-Tale Heart” to the class. I didn’t do it as well as Lori, but we got cookies afterward, because it was Christmas time. In retrospect, “The Tell-Tale Heart” seems like a weird Christmas story, but in a way I think it fits the season pretty well. Even now, I get a certain nostalgic feeling when I read it.

II. “MS Found in a Bottle”

Most of Poe’s stories are pretty straightforward, even the highly symbolic ones like “The Masque of the Red Death,” but “MS Found in a Bottle” is almost labyrinthine. A nameless man finds himself trapped on a massive ship heading further and further southward, surrounded by a crew of old men who totally ignore his existence. As a middle schooler, I assumed the narrator was trapped on a ghost ship. I thought that was pretty cool.

I read “MS Found in a Bottle” right around the time I first heard the rock opera Tommy, by the Who. I thought it would be awesome to have a rock opera based off Poe, with a couple other old-school horror and science fiction writers thrown in for good measure. It would be called Nightmare, and would have featured Captain Nemo, Dr. Moreau and the Raven all trapped aboard the ship from “MS Found in a Bottle,” menaced by Cthulhu. The only thing stopping me was a total lack of musical talent.

I still don’t have any musical talent, and I don’t think “MS Found in a Bottle” is about a ghost ship. In truth, I still don’t know what it’s about. We never know why reaching the South Pole obsesses the elderly sailors. Poe implies that the ship may actually be growing, alive somehow after centuries of floating on the ocean, but how this came to be we never know. The story is more Borgesian than Gothic, but I still love it for its surreality. And I still hope somebody someday will use it in a rock opera involving Cthulhu.

III. “The Conqueror Worm”

Over winter break of freshman year in high school, I was supposed to memorize a poem to recite for Humanities class. I completely forgot until the last night of vacation. In a panic, I stumbled around trying to find something to commit to memory so I wouldn’t fail the assignment. I knew it couldn’t be just any poem, either. I needed something cool, something I would at least enjoy having to read for the rest of the night. My Mom suggested Pablo Neruda or Shakespeare. Both fine authors, but—

Poe stepped in. I chose “The Conqueror Worm,” and in a spate of last-minute desperation, I managed to memorize it so thoroughly that even now, ten years later, I can quote large passages of it. I guess it’s fitting that a poem about the shortness of human life still carries for me a tincture of total desperation.

IV. “The Black Cat”

The thing that horrified me most about “The Black Cat” wasn’t the supernatural vengeance theme of the story, but the terrible things the narrator does out of “PERVERSENESS.” Knowing it’s wrong, he mutilates and kills his cat and wife. At twelve or thirteen, that was still enough to keep me awake at night. But at that age, a lot of things kept me awake at night.

I had a persistent realization how easy it would be for me to walk down to the kitchen, grab a knife and kill my parents in their sleep, or blind my dog with a razor, or degenerate into a depraved rapist. A lot of horrible things seemed easy to do, and maybe even hard to stop yourself from doing, once a kind of moral inertia took over. There would be no motive but “PERVERSENESS,” and those thoughts used to keep me awake a good number of nights.

I was ultimately diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and by then I had learned that I wasn’t a murderous, dog-blinding rapist. Now I live with my own black cat, Lavinia Whateley. She came to sit on my chest as I read Poe’s story. Listening to her purr, I remembered some of my old terror. It’s just as easy to snap a cat’s neck as pet it. I stroked Lavinia a bit more gently, and wondered at the terrors that compelled Poe to write this frightening, powerful, and heart-wrenching story.

V. “The Masque of the Red Death”

Sophomore year of college, I took a course on death in literature. The professor, dressed in tie-dye scarves and long skirts, was very invested in an idea she called “the work of mourning.” She would ball her fist into a talon to show that this was something you really had drag out of yourself. We read a lot of books in that course, some very good, most merely trendy. Notably, we ignored horror, and so ignored the one genre that repeatedly and unabashedly confronts death.

“The Masque of the Red Death” culminates in one of the most unflinching summations of human mortality ever written: “And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.” There’s no room for the work of mourning, because all those who would mourn are dead.

And there’s the rub. Edgar Allan Poe is a classic author, but he doesn’t perch so easily among the Emersons and Whitmans. I would call him a black sheep, but in reality I think he’s more like a raven among a flock of doves. Poe may not have turned into a transparent eyeball or sounded his barbaric yawp across the rooftops of the world, but virtually everyone recognizes “The Raven’s” melancholy “‘Nevermore!’” or the dull, muffled beat of a heart under floorboards.

That heart still beats. Like Prince Prospero’s black clock in “Masque”, Poe reverberates down two hundred years of literature, making us look up in a wonder still tainted by fear.