I can empathize with Gary A. Braunbeck. Much like the impressive hand behind 2005’s Keepers, I too once thought that my students could benefit by writing from the perspective of a fictional character. Specifically, during an assignment that coincided with Halloween, I tasked my eighteen to twenty year-olds with rewriting an already published and celebrated short story from a POV that the original author did not use. And like Braunbeck’s students, mine mostly failed.

In hindsight, I should not have expected any better. After all, many of my former students laughed at the concept of reading for anything other than a soon-to-be-forgotten test, therefore forcing them to read fiction (let alone actually making them write fiction) was an excuse for me to take years off of the latter half of my life. For the most part, their stories contained characters that spoke and acted much like themselves, and even more disturbingly, these characters contained as much depth as a kiddie pool. I had great students, but in order to become a good writer, one must be an even better reader. That is something that is hard to teach.

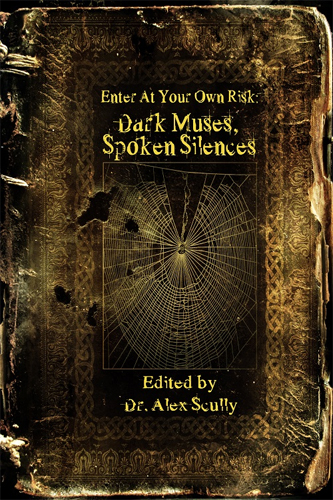

Despite the fact that myself and Braunbeck, who provided the introduction for this collection, had less than stellar experiences with this assignment model, Dr. Alex Scully and Firbolg Publishing still went ahead with the idea of having modern artists reshape and recast four selected classics from the horror genre. These four short stories are Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat,” Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu,” and John Polidori’s “The Vampyre; A Tale.”

While the first three are unlikely to raise a hackle or voices in dissent, Polidori and his tale’s status as a “classic” may be called into question. Undoubtedly, Polidori’s story, which was conceived of and outlined during the very same summer excursion in Switzerland that inspired Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, was the first major English language story to deal with the vampire, a figure of fear that had previously belonged almost exclusively to Continental writers and folklorists. As such, “The Vampyre; A Tale” deserves to be included in Dark Muses, Spoken Silences, even though it is far from a good piece of prose.

And while Dark Muses, Spoken Silences is worth buying for the four horror classics alone, its main thrust and purpose for existence are the ten short stories that were written in response to the Gothic “Big 4.” Some of these stories are excellent entries that do serve to revise and rethink their antecedents, while others only serve to show the painful reality that remakes and sequels are rarely better than the original. In Dark Muses, Spoken Silences, the good and the bad mix and cohabitate with one another.

On the good side of the spectrum, there are stories such as Marcus Kohler’s “The Horseman’s Tale,” Jon Michael Kelley’s “The Silent Highwayman,” and Timothy Hurley’s “Black Cats.” In Kohler’s tale, the headless Hessian speaks for himself, and the story he tells is full of pagan hints and suggestions that the fine old Dutch folks of New York were anything but God-fearing. Unlike his peers in this volume, Kohler, who is not a native English speaker, has a wonderful command of language and pacing, and even though “The Horseman’s Tale” is Kohler’s first published piece in English, it nevertheless adequately captures the cadences of an older, more refined brand of the Anglo-Saxon tongue.

Kohler’s tale also succeeds because, unlike Carole Gill’s “Katrina’s Confession” or T. Fox Dunham’s “Hollow Longing,” “The Horseman’s Tale” is less obviously influenced by Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow. Gill’s story, which turns Katrina Van Tassel into a satanic witch, bares the most obvious similarities with the film from 1999, while Dunham’s piece more obviously suffers from an explicit motivation (turning Brom Bones into a closeted homosexual) that runs counter to creating an interesting narrative.

For the Poe stories, the best one of the bunch is Hurley’s “Black Cats,” which views Poe’s most gruesome story from the point-of-view of Preston Thatcher—an executioner who had a hand in Poe’s mysterious death. It’s odd to see that the best version of “The Black Cat” relies upon a narrator that is not present in the original, but then again the silent supporting characters in “The Black Cat” are too tempting for many post-modern enthusiasts, and as such Blaze McRob’s “The Wife and The Witch” and “Satisfaction Brought Her Back” (which was penned by an anonymous author) give voice to both Pluto, the black cat, and the narrator’s wife. As with “Hollow Longing,” both of these short stories do not do much more than accomplish their stated mission—to write against the stereotypically abusive figure of the nineteenth century male. This figure happens to be Poe himself in McRob’s tale, while Anonymous busies him or herself with performing the logical fallacy of presenting a human’s perspective on animal life from the vantage point of an animal’s perspective.

The best that can be said of the poorer imitations of Poe and Irving is that they elicit strong reactions. This is not the case with either Mike Chin’s “Considering the Dead” or Gregory L. Norris’ “The Whisper of Cthulhu.” While neither story is either badly formed or half-heartedly delivered, both “Considering the Dead” and “The Whisper of Cthulhu” recreate the less praiseworthy aspects of Lovecraft’s fiction—his meandering, his convoluted diction, and his focus upon the surface level psychologies of flat, two-dimensional characters. Still, despite these poor choices, both Chin and Norris prove that the whole Cthulhu concept is too cool to truly ruin, and so their short stories are saved by the full framework of Lovecraft’s masterpiece.

The final story in Dark Muses, Spoken Silences is its best. After the melodramatic and verbose “The Tygre,” Jon Michael Kelley’s “The Silent Highwayman” comes roaring in to the final position, and its steampunk-esque toying with history actually works in its favor. In Kelley’s story, Ruthven, Polidori’s Byronic vampire, converses with Charles Dickens and Charles Darwin, and, on top of that, he directly engages with, and even takes part in, the rampant filth and disease of the London sanitation system of the 19th century. On the one hand, Kelley’s Ruthven harkens back to F.W. Murnau’s disease-spreading wraith, and as part of that Kelley alludes to the London cholera outbreak of 1854. On the other hand, Kelley’s vampire is a commentary on our death fetishes, especially our collective interests in the more prurient aspects of the “Big Sleep.”

Well, it’s safe to say that Dark Muses, Spoken Silences is better than your average English 101 composition. Not only is it a swell new entry in Firbolg’s Enter at Your Own Risk series, but it furnishes its readers with some new talent to follow. And while there are certainly lackluster passages in this tome, for the most part, the three exceptional tales more than make up for the riff-raff. Overall, this was a pleasurable read, and I am sure most horror fans will agree with this very simplistic statement. Please, pick up a copy of Dark Muses, Spoken Silences, but do enter at your own risk (sorry – couldn’t help saying that).

Enter at Your Own Risk: Dark Muses, Spoken Silences is currently available in paperback and as an eBook.