My wife hates H.P. Lovecraft. Ponder that for a second. That’s like Lyndon Johnson and Ho Chi Minh finding they had enough other stuff in common to put aside that whole Vietnam War thing and spend their lives together in mutual passion.[1] Truth is, I can understand why a lot of people aren’t Lovecraft fans; just like callous exploitation by the French government wasn’t the best introduction Vietnam could have gotten to capitalism, Lovecraft wrote a lot of (oft-anthologized) stories that aren’t going to convert the Cthulhu skeptic in your life. It’s too late for LBJ and Uncle Ho, but I’m going to make a last ditch attempt to steer my wife towards “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.”

“The Shadow Over Innsmouth” appeared in hardcover in Lovecraft’s lifetime—the only one of his works he lived to see published outside the pulps. The story of a decaying Massachusetts coastal town duped into breeding with a monstrous undersea race (the Deep Ones) who promises their children immortality, “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” is by far one of Lovecraft’s best, the product of a maturing author with an increasingly nuanced view of his trademark cosmic horror. In addition to the usual batrachian abominations, “Innsmouth” features a healthy dose of body horror, unnatural sexuality, suspense, and, contrastingly, the suggestion that unearthly terror can double as unearthly beauty.

The influence of “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” is vast, ranging from films (Stuart Gordon’s Dagon) to video games (Headfirst Productions’s incredible Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth) to music (Metallica’s 1986 song “The Thing That Should Not Be” features the memorably Innsmouthian lyric, “Hybrid children watch the sea/Pray for Father roaming free.”) It’s hard not to see the Deep Ones’ unholy shadow in 1954’s The Creature from the Black Lagoon, featuring another ancient fish-like monster with a strange and unexplained interest in the only female member of an expedition to South America.[2] Opening his story with a hushed-up government raid on Innsmouth, Lovecraft prefigured much of our current paranormal conspiracy lore over a decade before Roswell. In true Mythos fashion, “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” has netted a number of sequels and spin-offs, and a good range of them appear in Titan Books’s reprint of the 1994 anthology, Shadows Over Innsmouth.

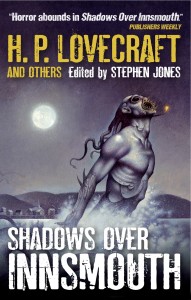

Edited by veteran anthologist Stephen Jones, Shadows Over Innsmouth features seventeen takes on the mysterious seaside town. Beginning with Lovecraft’s original novella and featuring contributions from some of the biggest names in the genre, Shadows, like all anthologies, has its peaks and valleys, but I’m happy to say the peaks are in the majority.

The first non-Lovecraft entry in Shadows Over Innsmouth is the late Basil Copper’s “Beyond the Reef,” which details the investigation into a murder at nearby Miskatonic University, and the discovery of tunnels beneath the school that lead to Innsmouth. Copper’s story makes for a good, brisk read, but he jettisons the Deep Ones in favor of snake-like aliens that possess and mutate unwitting humans. In another context, this setup would probably work on its own merits, but it lacks the elements of monstrous heredity and perverse sexuality that gave Lovecraft’s story such a punch.

David Langford’s “Deepnet,” in which Innsmouth becomes a Cthulhoid answer to Silicon Valley, suffers much the same flaw: a good idea that doesn’t fit the setting. While the concept of radiation from computers causing mutations and depravity is a neat one, the hints that the hybrid citizens of Innsmouth have been conscripted into programming is difficult to take seriously.

Kim Newman contributes two stories to the anthology, one under his own name and the other under his pseudonym, Jack Yeovil. Yeovil’s story, “The Big Fish,” is a wonderful noir take on Innsmouth involving a murdered mobster, his rival, and a bulgy-eyed femme fatale involved in an unsavory cult. Set shortly after Pearl Harbor in a thinly-disguised version of Raymond Chandler’s Bay City, “The Big Fish” nails the period atmosphere and voice perfectly with a seamless mixture of eldritch and hard-boiled. Newman’s “A Quarter to Three” is a vignette in which a pregnant girl awaits her “amphibian” of a boyfriend in a late-night seafood restaurant. While not as satisfying as “The Big Fish,” it makes for a whimsical little sketch and a welcome intermission from the grimness of the other stories.

Guy N. Smith’s “Return to Innsmouth,” unfortunately, is little more than a six-page retread of Lovecraft’s original story with a confusing ending. Smith’s style works well enough, but “Return,” like Adrian Cole’s “The Crossing” and Michael Marshall Smith’s “To See the Sea,” falls back too much on the Innsmouth formula of menacing townsfolk and secret ancestry. Of the three, “To See the Sea” pulls it off best, with a young couple going to the resort town where the wife’s mother was shipwrecked and nearly killed decades ago during a storm. Michael Marshall Smith is a capable writer, but I still found myself wishing he had chosen to tell the story of the shipwreck rather than the couple.

D.F. Lewis’s “Down to the Boots” is a beautifully lyrical portrait of an Innsmouth fisherman and his wife. I’m not sure I fully understood it, but its style was captivating enough that I didn’t care.

Ramsey Campbell contributes “The Church in High Street,” which has nothing to do with Innsmouth beyond featuring a town filled with strange occupants worshipping weird things (in other words, standard Lovecraft). That said, it’s a fun romp through underground corridors and forbidden secrets, and what self-respecting Mythos fan doesn’t like that?

David Sutton’s “Innsmouth Gold” has a promisingly creepy set-up: a down-on-his-luck wildlife photographer bets a friend he can find lost treasure in now-abandoned (present-day) Innsmouth. What follows is a tense, atmospheric story cut suddenly short by a rather uninspired monster chase. Sutton’s idea could easily have sustained a novella of its own, and I hope one day he’ll revisit it.

“Daoine Domhain,” by Peter Tremayne, ties the Deep Ones in with Celtic mythology through a secluded island off the Irish coast. The story stands out on its own eerie merits, but the cultural detail Tremayne invests in the piece also makes a nice change of pace from so many tales set in England and Massachusetts.

Brian Mooney’s “The Tomb of Priscus” also does a good job putting the Deep Ones in a historical context through the discovery of a cursed Roman tomb investigated by a priest and his occultist friend. It’s hard to say why Mooney made the narrator a priest, since his clerical vocation doesn’t seem to inform any of his actions (this is a shame—a theological take on Cthulhu could have been an interesting one), and the story ends with an uninspired deus ex machina involving incantations and Elder Signs.[3]

Brian Stableford’s “The Innsmouth Heritage” tackles the question of how Deep One-human genetics would work, making for a mournful and evocative yet oddly plausible story in which, in true Lovecraftian fashion, science can’t explain everything.

I’m not sure you could call Nicholas Royle’s “The Homecoming” a Mythos story, aside from a few stray references. In fact, I don’t think there’s anything supernatural happening in this portrait of a Romanian refugee returning to Bucharest after the death of dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. But Royle’s story is infused with a rich atmosphere of decay, paranoia, and insanity that make it by far one of the scariest stories in Shadows.

Full disclosure: I was ready to hate Brian Lumley’s “The Bell of Dagon.” I don’t like Lumley’s take on the Mythos at all (we’re talking about the guy who gave Cthulhu a benevolent twin named Kthanid),[4] and I find his style annoyingly chipper. I was semi-pleasantly surprised; Lumley’s story of a young man who buys a house on the English coast following the death of its eccentric and reclusive owner is indeed annoyingly chipper. Fortunately, good twin Cthulhoids are nowhere to be found and the tale features a well-done climactic pursuit through the sea caves below the house.

The volume ends with Neil Gaiman’s “Only the End of the World Again,” starring a werewolf P.I. who sets up shop in Innsmouth. The writing is smooth and enjoyable (what else do we expect from Gaiman?) but the lycanthropy element doesn’t work. Thematically it should, since werewolves and Deep Ones are both the result of human-to-beast transformations. Yet in the end, Gaiman’s werewolf (named Lawrence Talbot, of course) feels superfluous, an oddly mundane element amid the over-the-top weirdness of the Mythos. Even sub-par Gaiman is still very good, but “Only the End of the World Again” doesn’t quite stand up to some of the other stories in the anthology.

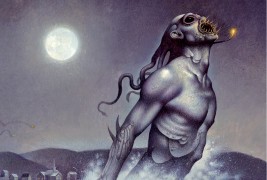

Lastly, three of Shadows’s most talented contributors weren’t writers at all, but artists Dave Carson, Jim Pitts, and Martin McKenna, whose pen & ink illustrations grace the interior. Working in three distinct but equally engaging styles, Carson, Pitts, and McKenna’s eye-popping portraits of the Deep Ones and their blasphemous gods (a gruesome image of “Mother Hydra” at her most fecund stands out as a particular highlight) give Shadows a Necronomicon-ish charm.

One of the best features of Shadows Over Innsmouth is that unlike a lot of Mythos collections which presuppose familiarity with Lovecraft, Jones has constructed the anthology to be a self-contained whole. By including Lovecraft’s original story along with the sequels and spin-offs, we get Innsmouth from all angles, of interest to long-time Mythos fans and new initiates alike. It took decades to normalize relations with Vietnam, but if you have Cthulhu-denying heretics in your life, you could do worse than to introduce them to Shadows Over Innsmouth. Preferably before the unspeakable sacrifice.

[1] Rule 34 strikes again.

[2] When I saw this movie as a kid, I figured the Gill-Man just wanted to eat her. Thanks to my friend Ken Collison for calling a Deep One a Deep One.

[3] What is the Elder Sign? Lovecraft never really says, but later writers have made it into a sort of Cthulhu-repelling crucifix. Many a bad Mythos story ends with Elder Sign-toting protagonists offing a previously-unkillable monster.