It started in second grade, when my parents rented me the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce Hound of the Baskervilles. I liked it, but I don’t remember much now except that Rathbone’s Holmes was a consummate English gentleman and Bruce’s Watson was an idiot.[1] I liked Granada Television’s The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (aired Stateside on PBS’s Mystery), starring Jeremy Brett as Holmes and David Burke/Edward Hardwicke as Watson, far better. From the eerie violin intro panning over the streets of Victorian London, The Adventures let you know this wasn’t a world where everything was topping and righty-ho except the occasional greedy relative and his phosphorescent dog. This smoky, messy, violent place required far more than the occasional hygienic application of logic to redeem. And unlike the blandly heroic Rathbone, Brett conveyed the eccentricity, obsession, and perhaps flat-out madness Doyle depicts so vividly in Holmes.[2] I’m certain that this gritty world/insane hero combination laid the path to my later fascinations with Martin Scorsese and H.P. Lovecraft.[3]

I think the reason Sherlock Holmes remains such an iconic character rests on more than just his memorable deductive skill; he’s also fascinatingly weird. We don’t know a lot about Holmes. What was his upbringing like? Who were his parents? What is the source of his nigh-maniacal obsession with solving problems? We can’t answer a lot of these questions about, say, James Bond, but whereas we expect such incompleteness from a boringly perfect Cold War functionary like Bond,[4] what we don’t know about Holmes makes his psychic terra incognita even more fascinating. I’ve seen theories that Holmes is a high-functioning sociopath, a Jew desperately trying to win the approval of an anti-Semitic society, or, of course, gay. Kingsley Amis, in his essay, “My Favorite Sleuths: A Highly Personal Dossier on Fiction’s Most Famous Detectives,”[5] rather defensively states that, “Holmes is no fag.” I’m not convinced. I’m equally skeptical that a frustrated, sublimated, homosexuality rules Holmes’s interior life. But I do think that were I a gay man, I might find something to identify with in his secrecy, his attachment to Watson and his seeming need to keep all others distant. Sherlock Holmes endures, perhaps, because his negative spaces look so much like our own.

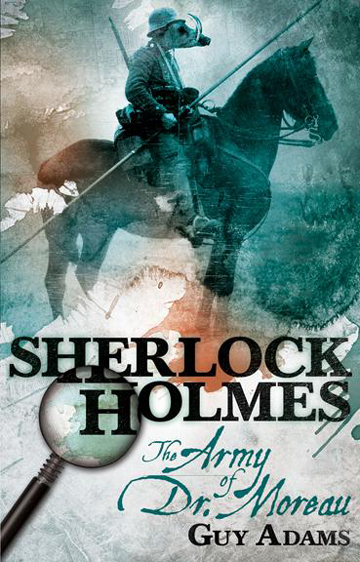

Guy Adams’s Sherlock Holmes: The Army of Dr. Moreau, published by Titan Books, taps into a long tradition of pitting the great detective and his assistant against equally iconic literary and historical villains. This began in Doyle’s lifetime, when the reading public implored him to send Holmes against Jack the Ripper. While Doyle never took the bait, various authors and directors have matched Holmes against not only the Ripper but Dracula, the Nazis, the Cthulhu Mythos,[6] and a rogue’s gallery of other monsters. Adams at last brings H.G. Wells’s Dr. Moreau, by far my favorite mad scientist, into the mix. The detective and the doctor find themselves investigating a series of brutal killings somewhere between murders and animal attacks, all at the behest of brother Mycroft Holmes and his government-affiliated Diogenes Club. The Club, as we learn, has had some uncomfortable past associations with a certain vivisection enthusiast, and Mycroft suspects he may not have died in the South Pacific after all.

I haven’t read Adams’s previous Holmes pastiche, Sherlock Holmes: The Breath of God, so I can’t say if The Army of Moreau rates better or worse by comparison. The dialogue, tone of narration, and the setup are dead-on.[7] Adams’s Holmes and Watson are the same Holmes and Watson I loved watching on Mystery as a kid and love reading about in Doyle’s stories now. Even some apparent anachronisms, like a reference to “terrorists,” are in fact no such thing (the term dates to the French Revolution, if you can believe). In both historical and literary research, Adams has done his work, and his respect for all the material, whether from Wells or Doyle, is obvious. My biggest difficulty with The Army of Dr. Moreau doesn’t hinge on any of these harder-to-nail factors. My real problem is with the plot.

The idea of Moreau as a former contractor for the Diogenes Club (who commissioned an elixir that prompts rapid evolution in its subjects, potentially enabling soldiers to adapt immediately to hostile environments) is inspired. But the book’s most glaring disappointment is **SPOILER!** that Dr. Moreau never actually appears in the novel. The villain is far less compelling than Wells’s sinister doctor, and the climax is rushed and more than a little muddled. This is unfortunate, because it’s obvious that Adams is talented enough to write a taut confrontation between these two literary landmarks. I suspect the switch was done to preserve suspense, but part of the fun of mash-ups like this is the fact that we know Holmes and Moreau will meet, and brilliant deduction will be matched against cold and ruthless scientific intelligence. **SPOILERS END!**

This problem runs through Army. Professor Challenger (another Doyle character, most famously from The Lost World) is one of the Club’s other agents, but Adams gives him little page-time with Holmes. Though less well-known (you don’t hear people say, “No shit, Challenger,” after all), he’s a wonderfully quirky character in his own right: a loudmouthed expert on zoology who, like Holmes, balances galling obnoxiousness with inarguable genius. Maddeningly, Adams gets Challenger’s voice as surely as he gets Holmes and Watson, but shies away from making full use of this great setup.

I don’t think Adams is a lazy writer. His research and attention to voice and detail argue the opposite. It’s equally obvious to me that he respects the mythoi he’s writing in and wants above all to honor the worlds of Doyle and Wells. However, his novel reminds me a little bit of a neatly-arranged but unused toy chest. Sure, Holmes and Moreau are famous literary characters, but we’re playing with action figures here, not polishing Ming vases. I wish Adams had tried something a bit crazier with The Army of Dr. Moreau. Holmes and Watson faced a beast man before, the monkey hormone-infused Professor Presbury in “The Adventure of the Creeping Man.” Could there be a connection? Leaving Doyle’s canon, literature from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century bequeathed us a whole trove of animal characters. The idea of a humanoid White Fang or Black Beauty siding with Holmes against their maker sounds like literary blasphemy—but wouldn’t it be kind of fun?

I won’t say Guy Adams has done a bad job. On the hard parts—things like voice and atmosphere that fans tend to complain least helpfully about—he succeeds abundantly. I just don’t get the sense he enjoyed writing it, which in a book with such a neat premise is a shame. Much as I wish I could hold up two freshly sewed-on thumbs and howl my admiration, I can’t unabashedly recommend Sherlock Holmes: The Army of Dr. Moreau; its pacing is a bit too messy and its promise too unrealized. But my feeling is that a writer who does all the hard work as well as Adams is a writer who won’t take long to get the rest of it right as well. Keep your eye on him, but hope to God he doesn’t go to medical school.

[1] This characterization of Watson derives exclusively from the Rathbone and Bruce movies, and strikes me as a bit unfair. Doyle makes clear that Watson is a capable doctor and an intelligent man; he just looks stupid next to Holmes because everybody looks stupid next to Holmes.

[2] As a child of the “Just Say No!” era, I was horrified to find that my hero was a cocaine and opium addict. How could Holmes have fallen for one of those sleazy ‘80’s pushers? After all, I had seen enough cartoons to know that only stupid and weak people became drug addicts. Nancy Reagan neglected to inform me that in Holmes’s time and place, both substances were 100% legal. Interestingly, Doyle has Holmes use drugs to stave off the boredom and intellectual restlessness he feels when he has no cases to solve, indicating that a nineteenth century author understood the mechanisms that can drive people to self-medication and addiction better than a whole cadre of late twentieth century demagogues.

[3] For the record, I thought Guy Ritchie did an amazing job with his first Sherlock Holmes movie. The second. . .disappointed.

[4] Daniel Craig is by far the most interesting Bond in my opinion.

[5] This interesting examination of detective fiction appeared in the December 1966 Playboy and is a laudable defense of genre fiction (in this case, detective stories) by an establishment writer and critic. Amis has scant regard for the American hardboiled tradition, but we would expect as much of an Oxford culturatus, wouldn’t we?

[6] Frogwares released a fantastic puzzle/adventure game a few years ago for the PC entitled Sherlock Holmes: The Awakened featuring Holmes and Watson investigating a series of murders committed by a cult worshipping Cthulhu. Frogwares mixed Lovecraft with Doyle in exactly the right measures. Though The Awakened leaned heavily on the Nigel Bruce “Dumbass Watson” formula, the game was otherwise incredible.

[7] Adams is also an actor who has portrayed Holmes on two occasions.

2 thoughts on “Sherlock Holmes: The Army of Dr. Moreau Book Review”

Comments are closed.

Ever read Hounds of the Durbervilles by Kim Newman? Great fun read for a Holmesian.

No, but thanks for the recommendation, Nik! Newman’s done some great stuff in the Victorian mashup vein. “Anno Dracula” comes to mind most forcefully, although sadly Holmes is only mentioned by name, having been confined in a concentration camp with other dangerous political subversives like Bram Stoker. I hear Newman has another book that’s a typical Holmesian adventure of deduction, but starring Moriarity and Moran instead of Holmes and Watson.