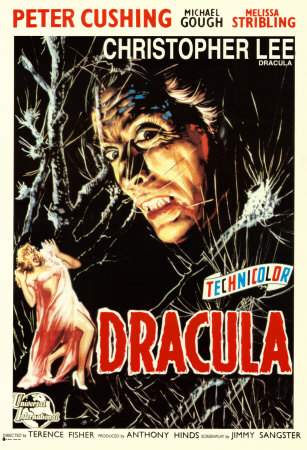

“It’s rather clanging, don’t you think?” The professor was a short, fashionable blonde, who, despite her 40-plus years of age, still talked like a preening Valley Girl. During that day’s class, the target of another one of her half-formed diatribes was Horror of Dracula –Hammer’s lurid take on the Count Dracula story from 1958. Most horror enthusiasts will tell you that Horror of Dracula, which stars Christopher Lee as the Count, Peter Cushing as the crusading Van Helsing, and Terence Fisher as the film’s brilliant director, is an undisputed classic—an opening salvo in Hammer Studio’s war on the dodgy, tired horror films of Hollywood.

This particular professor didn’t see things that way. For her, Horror of Dracula represented a very businesslike approach to horror, with a curt, almost economical Dracula and a Van Helsing who approaches his fight against evil like a scientist approaching a Bunsen burner. On top of it all, what this professor detested the most about Horror of Dracula is its soundtrack. She spent an entire day of class calling James Bernard’s score “abrasive” and “not entirely in synch with the film’s action.” Her repetitive criticisms got a few people in the class on board with her, while her mere presence and force of opinion guaranteed that the apolitical majority would be on her side by default.

I, however, am a contrarian. Ever since renting Tod Browning’s Dracula on VHS from a video store (remember those?) in the mid-‘90s, I have been obsessed with vampires. Naturally, after graduating from Karl Freund’s lush German Expressionism, I moved on towards more sanguine camerawork. After gorging myself on the Universal monster films of the 1930s, I turned to the Hammer films of the 1950s and 1960s. And since vamps were my favorite bumpers in the night, Horror of Dracula was the first Hammer film that I ever saw.

What struck me then about the music was not so much its abrasiveness, but its appropriateness. Fisher’s 1958 flick is the cinematic equivalent of a haymaker, and as such it needed a soundtrack with a punch. Enter James Bernard, a former RAF airman and a known associate of the composer Benjamin Britten. Even though he had been scoring films since the mid-1950s, and even though he was responsible for the music of Hammer’s first breakout monster movie (The Curse of Frankenstein), it took Horror of Dracula to give the world its first full taste of Bernard’s genius.

The film opens with an ominous shot of a stone eagle before spreading out to include the entire outline of a Central European castle. Making things all the more uncomfortable is the music, which includes heavy drums, a gong, and military-sounding horns that are always playing in descending notes. This music is loud and full; it’s a far cry from the more minimal or popular approaches that characterize much of today’s horror films. Softness is also at a premium in Horror of Dracula, thus Lee’s laconic Dracula is contrasted by a soundtrack that exudes all the explosive energy of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

This allusion to high culture is not done in jest or to be provocative; Bernard’s Hammer scores are really that good. The son of a British army officer who was born in India’s volatile north-west frontier (which is in today’s Pakistan), Bernard first showed his musical genius at a tender age whilst dabbling with a child’s piano in his family’s Gloucestershire country house. Music teachers encouraged him, and before long Bernard was deeply immersed in the study of music at Wellington College.

While at Wellington, Bernard met both Britten and Peter Pears, a popular English tenor. According to Bernard’s obituary in The Guardian (dated August 20, 2001), Britten and Pears were at Wellington in order to “discuss the staging of the new opera Peter Grimes [sic] with the designer and schoolmaster Kenneth Green.”[1] Apparently, Britten and Pears were impressed with Bernard’s talents on the piano and trombone, and as a result kept in touch with the young man even as he was performing his national service from 1943 to 1946.

After being demobilized by the RAF, Bernard studied under Imogene Holst, the daughter of Gustav Holst[2], and Herbert Howells, a musician most known for his Anglican Church compositions, at the Royal College of Music. Bernard graduated in 1949 and then promptly met and befriended the writer Paul Dehn. Dehn would become both Bernard’s professional and life partner until his death in 1976. In one of their very first collaborations, Bernard and Dehn wrote the screenplay for 1950’s nuclear age thriller Seven Days to Noon. In 1951, Bernard and Dehn won the Oscar for “Best Story”—a feat that neither would reach again even though Dehn was nominated for “Best Adapted Screenplay” for 1974’s Murder on the Orient Express.

This lack of critical acceptance became the norm for Bernard, who, after working as a copyist and sometime orchestrator for the opera Billy Budd, landed a job as the music coordinator for the Quartermass radio program on the BBC. From there, Bernard caught the attention of Hammer Studios, and by the 1960s, Bernard was often responsible for two scores a year for the company. Among his credits are such titles as Kiss of the Vampire (1963),which is often singled out because of its Rachmaninov-derived piano concerto, The Gorgon (1964), and The Devil Rides Out (1968), which is arguably Hammer’s best all-around film.

Still, despite Bernard’s numerous scores and his many years spent with Hammer, he is most remembered for his contributions to two of Hammer’s most popular creatures—Dr. Frankenstein and Count Dracula. In 1957, Hammer released The Curse of Frankenstein—the film that helped to establish “Hammer Horror” as a recognizable brand. By taking a well-known set of characters from a well-received Gothic novel from an earlier epoch, Hammer played up what was recognizable and added in a little sex and violence just to secure success. James Bernard scored the film, and it was this orchestration, with its foreboding strings and suspenseful brass, that first outlined what can be characterized as the Bernard sound. While not as classy or daring as Bernard Herrmann (who, after all, was more interested in the interior psychosis of demented human characters), Bernard did perfect his own style of bombastic, yet decidedly elegant compositions. And unlike Herrmann, Bernard seemed little interested in jazz, preferring instead the music of the Continent.

Some of this could be labeled as snobbery. In the book James Bernard, Composer to Count Dracula, author David Huckvale links Bernard’s connection with the Hammer version of Dr. Frankenstein (which was usually played by Peter Cushing) with Bernard’s own aristocratic blood. It seems that, according to Huckvale, an Irish aristocrat is the best choice for any attempt to musically capture a Swiss aristocrat.

Blue-blooded preferences aside, Bernard’s score for The Curse of Frankenstein helped to make him, like director Terence Fisher, one of the hands responsible for the many hallmarks of the Hammer Horror era. While Fisher made glossy, grandiose pictures that helped to usher in a brief revival of Gothicism, Bernard crafted gigantic scores that seemed to occupy every aural space available. In the fan-favorite The Plague of the Zombies, Bernard also showed his willingness to experiment, with certain passages highlighting his work with bongos and other non-European percussion instruments.

But even though The Plague of the Zombies, with its Haitian subplot, allowed Bernard to flirt with the then en-vogue sounds of the so-called Third World (Bernard would do this again with 1974’s The Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires), Bernard’s established sound is still the primary element in that score, with building crescendos, a plodding low-end, and an excessively dramatic horn section.

Bernard would constantly revisit these trademark elements throughout his character. Few complained about the deficiencies in Bernard’s work mostly because his work was associated with films that were almost universally deemed as a subpar. And as Bernard went deeper into his career, the type of films that he worked on only continued to plummet. By 2000, the man who had written the brilliant score behind The Horror of Dracula was reduced to penning the music for TV’s Bloodsuckers.

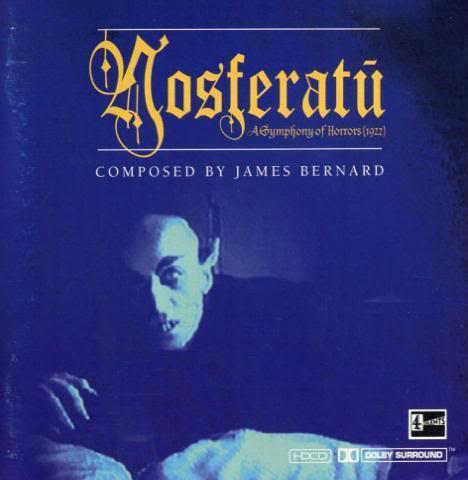

While it would seem permissible to conclude that the story of James Bernard is the story of a well-liked composer who ended his life in a semi-tragic state (mostly forgotten, criminally under-appreciated), this attitude would gloss over not only Bernard’s legacy (which is so thoroughly ingrained in the Hammer Horror mystique that most viewers don’t even realize how iconic Bernard’s music actually is) but it would also do a disservice to Bernard’s greatest work. In 1995, silent film historian Kevin Brownlow, an admirer of James Bernard’s work with Hammer, asked the composer to write a score for his restoration of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu. What Bernard eventually turned in to Brownlow was a masterpiece.

In just over an hour of music, Bernard’s Nosferatu symphony presents a complex journey of emotions and soundscapes. Unlike his work in sound films, Bernard’s Nosferatu, which stands on equal footing with Hans Erdmann mysterious original, is expansive and is allowed to be a project entirely within and of itself. This is the reason why the prestigious City of Prague Philharmonic was chosen to perform the score, and this is the reason why this project was collected together for Bernard’s first ever CD release.

In his rendition of Nosferatu, Bernard used what he had learned during his Hammer days and even expanded upon certain elements such as the use of trumpets, the tuba, the trombone, and the lower register woodwinds. The ultimate result of course was a 1997 restoration film that contained a film score that seemed as good if not better than the one that had debuted during the 1922 premiere. Upon listening now to Bernard’s score for Nosferatu (which is currently available in its entirety on YouTube), it’s hard not to think that this is indeed the original score for Murnau’s film—the two just go together so seamlessly.

Maybe this is because Bernard has come to embody the sound of vampires. His music, with its evocative, shadowy quality, perfectly mirrors the haunting inhumanity of one of the world’s greatest monsters. Plus, in a weird turn, like vampires, Bernard’s music feels somehow more alive and more vibrant than its brighter contemporaries. There is a tangible excitement in every one of Bernard’s scores, and although moviegoers rarely pay attention to the subtle nuances of film music, most if not all would instantly recognize the deficiency in any Hammer scene that is not set to the music of James Bernard.

[1]Gleason, Alexander. “James Bernard: Composer whose scores added chill notes to Quartermass, Frankenstein and Dracula.”

[2] Holst, the great British composer of his generation, is most famous his suite The Planets – a must listen for all readers of this article.

One thought on “The Music of James Bernard: Monster Virtuoso”

Comments are closed.

I cannot believe that no one has commented on this piece. I knew James Bernard pretty well and this assessment, while not being exactly mine, is cogent and informational which serves the memory of James Bernard very well. He always said that he never thought of just phoning it in as some critics have implied at times, and always tried to embody the crux of the story. Always in service of the story!!! Thank you Benjamin Welton for your work!