It used to be a schoolyard fable that Scooby-Doo began with a stoned conference. The creators, who were too busy smoking weed, did not notice a large dog entering the conference room. After a while, the weed, which must have been laced with LSD or some other hallucinogenic, started to take over and the gathered men all began hearing the dog talk to them. Rather than kill à la David Berkowitz, the men decided to make a television show out of their strange experience.

This is of course one of the more ridiculous origin myths in the history of oral storytelling. The only reason for its existence has to do with the perceived recreational choices of both Shaggy and Scooby-Doo. After all, like stoners, the two eat constantly and they even dine on food they find in supposedly haunted houses. Conversely, Shaggy’s ability to talk to Scooby-Doo, a large Great Dane, also denotes the possibility that the hirsute youth is not unused to toking it up.

The fact remains though that the Scooby-Doo franchise was not born out of the drug culture of the late 1960s. In fact quite the opposite is true. In 1968, the year before Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! debuted, the parent-run Action for Children’s Television (ACT), which was based out of Newton, Massachusetts, began their attack on Hanna-Barbera, the production company that would eventually create Scooby-Doo.

But before the mystery adventure show could get off the ground, Hanna-Barbera had the unenviable task of canceling most of their popular cartoons. In particular, ACT demanded that the production company cut out their action-oriented cartoons such as Space Ghost, Johnny Quest, and The Herculoids. ACT found these shows to be too violent for children, and as result, Hanna-Barbera not only cancelled these programs by 1969, but even invited parental watch groups to serve as advisors for future programs.

Nowadays, such complaints look downright silly. Even in our increasingly over-protective environment (especially regarding children), the action-adventure cartoons of Hanna-Barbera seem entirely harmless. But nevertheless the ACT boycott, as well as the pressure campaigns conducted by other groups, forced Hanna-Barbera to look for programming alternatives.

It was in this climate that Scooby-Doo was born. After the CBS producer Fred Silverman created a smash hit with the animated Saturday morning program The Archie Show, he contacted both William Hanna and Joseph Barbera with the idea of creating another Saturday morning cartoon based around the idea of a crime-solving group of teenage musicians. Specifically, according to authors Laurence Marcus and Stephen R. Hulce, Silverman envisioned a show that was a cross between the I Love a Mystery radio serials from the 1940s and the live-action sitcom The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. The latter show proved to be incredibly important in the development of the Scooby-Doo franchise, for Bob Denver’s portrayal of the beatnik hipster Maynard G. Krebs was an easy prototype for Norville “Shaggy” Rogers (who was primarily voiced by radio personality Casey Kasem).

These influences, along with the comic strip Marmaduke and Hanna-Barbera’s trademark style, helped propel Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! and its many successors into superstardom. The franchise is everywhere in popular culture, from everyday catchphrases to real-life Mystery Machines that occupy highways and driveways worldwide. More than that, even though the show premiered all the way back in 1969, it’s still going strong today, and one of its most recent incarnations (Scooby-Doo! Mystery Incorporated) received much in the way of critical acclaim and viewer appreciation.

It’s safe to say that many viewers think of Scooby-Doo as a self-contained entity—a circular universe of sorts. In this matrix, the franchise is the creator and executor of its genre—the horror-mystery which always proves to be human in origin (with a few exceptions). This idea is of course incorrect, and it’s important to understand some of the older roots of Scooby-Doo.

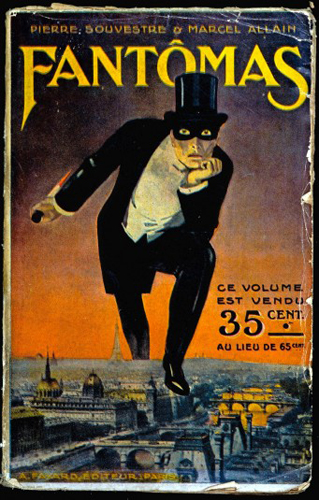

Like a lot of things in popular culture, the roots of Scooby-Doo can be traced back to the pulp magazines of the early twentieth century. Before World War I, European writers expressed a keen interest in the idea of crime and master criminals. Borrowing from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Moriarty (the arch nemesis of Sherlock Holmes) and the pseudoscientific claims of early criminology, these pulp writers created larger-than-life villains who seemed to possess supernatural powers. Famously, the French writing team of Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre created the masked criminal Fantômas in 1911. In just three years (1911-1914), Fantômas appeared in a staggering thirty-two novels and five film serials directed by Louis Feuillade. In each product, Fantômas, a master of disguise who can easily evade capture in either a fake identity or his trademark black mask and outfit, outwits the French police with an unearthly ability to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time. In fact, the first novel in the series opens with this very idea:

“Fantômas.” / “What did you say?” / “I said: Fantômas.” / “And what does that mean?” / Nothing…Everything!” / “But what is it?” / No one…And yet, yes, it is someone!” / “And what does that someone do?” / “Spreads terror!”

Fantômas really does live up to this introduction, and from murder to terrorism, Fantômas is one of literature’s most evil creations. Oddly enough, this pulp character had a profound impact on the French Surrealists, who were a collective of Left Bank intellectuals who had grown dissatisfied with bourgeois culture. In particular, the Surrealists sought to highlight the nihilism inherent in modern life, and as a result they found a hero in Fantômas—a criminal who does what he does in the name of senseless violence.

While Fantômas had poems and paintings dedicated to him, other pulp villains carved out their own space in the cultural landscape. Another French criminal—Arsène Lupin—cornered the gentleman-thief market along with the British creation A.J. Raffles (created by E.W. Hornung, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law), while antihero vigilantes such as The Shadow, The Phantom Detective, and The Spider paved the way for later comic book superheroes such as Superman and Batman.

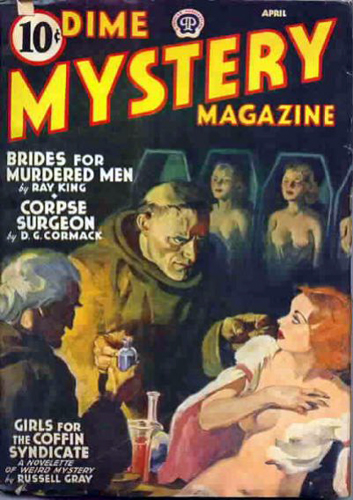

Although these character-driven pulps would go on to have the most lasting impact, they did not represent the entirety or even a large fraction of the pulp magazine market. Alongside these pulps were pulp magazines that specialized in Western tales, war tales, spicy romances (a sort of softcore porn), detective stories, and even weird tales (a type of horror fiction best exemplified by the magazine Weird Tales and authors such as H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, and Robert E. Howard). The weird menace pulps, a sub-genre connected to the horror, weird, and crime pulps, debuted in 1933. In that year, Dime Mystery Magazine started a new trend by publishing stories that presented a mixture of horror, torture, and other bizarre pastimes. Prefiguring the later Italian school of giallo, these weird menace pulps saw their heyday between 1934 and 1937, and in that time they presented a well-defined formula:

Usually, some horrible, devilish, and to some degree, supernatural being was threatening the well-being of all, but in most cases caused a great deal of torture and sadistic attacks on women. The pulp covers usually captured the essence of the torture and showed girls in various stages of torture and nudity. Our hero, usually after his girlfriend has been taken hostage, must now confront the evil villain. After saving the day, our hero then explains how the devilish villain is only a human and was using the latest in high-tech science to scare the victims so that he may gain in worldly possessions (Vintage Library).

To put it more succinctly, Robert Kenneth Jones, in his excellent book The Shudder Pulps: A History of the Weird Menace Magazines of the 1930s, characterizes these stories as “a form of mystery story in which the villain perpetrated seemingly supernatural deviltries, which were logically explained at the end.” This then is the origin of the Scooby-Doo plot formula, which goes something like this: the Mystery, Inc. gang stumble upon strange goings-on, discover a masked or otherwise concealed monster, find a crime underlying the recent appearance of said monster, and then unmask the monster as a human criminal. Essentially, Scooby-Doo watered down the weird menace pulps, which were often extreme in their depictions of sadism and violence. Also, although the weird menace pulps borrowed heavily from the mystery magazines and novels of the day, actual mysteries took a backseat to torture porn in these tales.

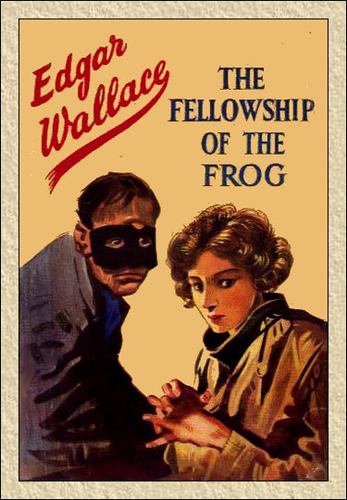

Enter Edgar Wallace—the other major influence on Scooby-Doo. Born an illegitimate child in London in 1875, Wallace began his career as a war correspondent and journalist for the news agency Reuters and the newspaper the Daily Mail. In order to pad his bank account, Wallace took to writing crime novels in 1905. By the 1920s, Wallace was one of the most prolific and popular writers in the world. His books, which are today mostly out-of-print or free online, influenced not only the emerging pulp magazine market but also film, and after World War II, the West German-Danish company Rialto Film used his novels as the basis for their line of krimi films that began in the late ‘50s and ended in the early 1970s.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Wallace primarily wrote crime novels as opposed to detective novels. As such he was the masculine opposite to Agatha Christie’s more female-friendly series of genteel mysteries. As part of this, Wallace’s novels place a premium on action and motion, and usually his criminals lean more towards the master villain line of things. In such novels as The Crimson Circle (1922), The Dark Eyes of London (1924), and The Black Abbot (1926), Wallace uses supernatural motifs and the ambiance of mystery inside of stories about criminals guarding hidden treasure or secret blackmailer rings that disguise themselves as frogs or demonic priests. Straightforward, lean, and always sensational, Wallace’s novels helped to keep alive the master criminal narrative during his short lifetime.

Even though it was born out of necessity, Scooby-Doo is very much a piece of a larger pulp puzzle that stretches all the way back to the Edwardian era. Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! was not the first attempt to turn pulp stories into kid-friendly entertainment, but it is certainly one of the more successful. Legions of adults were first turned on to horror and mystery fiction because of the Scooby-Doo franchise, and without this Saturday morning education it is quite possible that many novels, short stories, and films would have gone unmade or unwatched.

One thought on “The Pulp Roots of Scooby-Doo”

Comments are closed.