The enviably towering apartments and fierce Vidal Sassoon stylings aside, it is quite harsh and sad to realize that throughout half of Roman Polanski’s 1968 horror and suspense classic, Rosemary’s Baby, we are watching a lonely Midwesterner gestate and produce the inhuman spawn of the Devil Himself. Based on Ira Levin’s 1967 shocking, best-selling novel of the same name, Rosemary’s Baby leads us to half-expect its star Mia Farrow to ascend to a place on the New York City catwalks by the end—and not through the tunnel of hysteria and derangement which precedes her shrewd, solitary detective work on those who profess to care for her the most.

With a husband who enjoys conceiving Lucifer, Jr. “in a necrophilia sort of way” (while Rosemary is passed out) and batty older neighbors who insidiously administer the desserts and shakes to feed the demon baby, one is not sure whether to categorize the film as pathetic, absurd or wholly plausible, even in modern times. While playing dress-up and piano jazz in her sprawling and lonely Central Park West apartment gem, Rosemary is bullied into a spine-chilling truth: Her husband has bartered their unborn child to the Satan-worshipping neighbors’ local international coven, in exchange for instant fame and glory as a major American actor.

The 1967 novel performs a masterful authorial trick: Its blah language, staccato storytelling and pedestrian narrative seduce readers into believing nothing really is going on. Truly, nothing is. Upon arrival into an elusive apartment at the fictitious Bramford, Guy and Rosemary Woodhouse nest as hopeful honeymooners on the verge of all the children, success, wealth and stability they can dream of. Polanski’s direction of a young John Cassavetes leaves no doubts as to how this scenario will unfold with such a doting and patient wife, who takes more joy in hanging curtains than hanging out with the girls; Guy Woodhouse is a prick. While the film leaves her entire large family (5 siblings and 16 nieces and nephews) absent, with very little explanation, the novel reveals that the very Catholic Rosemary has fallen for a Protestant/Jew that her family does not approve of. The increasingly paranoid Rosemary imagines her punishments of Hail Marys and family scorn should she cry out to the gang back home, but it is not known why her sad reality of having witches as neighbors is not well worth the shame.

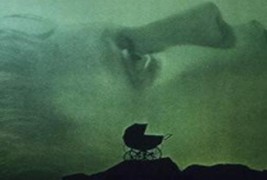

What is known is that the baby would have been registered at Bergdorf-Goodman, Barney’s or Tiffany’s. The cinematic feast for the eyes gives no indication that the expertly detailed railroad apartments, glowing white furnishings and carpet, and gingham housedresses or silk “baby night” pants suits are the modern swathings of the Devil’s conception. However, the glamour and vogue carry the masterpiece’s slow-plot and lullaby tone like art gallery pieces for the leisurely to spend their fair share of time on. Filmed in the 1960’s and starring one of the era’s most popular gamine beauties, the generation of Hair and Blaxploitation may have relished the sacrilegious punch lines, pot-smoking revival of the couple’s young friends, and visions of bestiality that mark the transformation of Guy into an inhuman incubus who rapes Rosemary. Postmodern audiences desensitized to gore, impalements and bloodbaths may miss the point. Rosemary regresses into a malnourished, shadowy ghost who chews on raw meat and is the human pod for a clawed little beast that the cameras refuse to even show us…yum, yum. Very few could avoid succumbing to the type of chills which linger and permeate long after the credits roll.

Rosemary and Guy leave behind one friend in their former building, a writer named Hutch (Maurice Evans). Hutch expresses concerns about witchcraft scandals in the Bramford. Of course, who believes in that anymore? Rosemary and Guy wave off Hutch’s concerns, and prepare to come out as “New York High Society” in the classy building. The couple moves into their new bare apartment, enjoy takeout, start to make love and notice that they can hear faint murmurings through the wall at the end of the apartment. Most would have never unpacked, they’d have moved. Yet, Rosemary’s Midwestern naiveté and trust mutes this as just her latest adventure.

The complicated, ensuing plot entails Rosemary briefly meeting a young woman in the dank basement laundry room—a former drug addict who waxes poetic about the elderly couple who has taken her in. Through this young woman, Terrie, Rosemary is introduced to the movie’s herbal weed: Tannus Root – which will be fed to her to provide sustenance for the demonic child and it will also identify her satanic victimizers via horribly malodorous crumbles steeped inside a hideous medallion.

A couple of days later, as Rosemary and Guy return home from a show they find Terrie crumpled on the sidewalk of the Bramford. The introduction of one of horror’s most magnificently-portrayed and underrated stars occurs with an upward pan of the camera to the nonchalant faces of Minnie and Roman Castavet (Ruth Gordan and Sidney Blackmer). They identify themselves as the neighbors who saved Terrie from destitution, substantiating claims she was troubled. They clarify that they are the adjoining neighbors to the Woodhouses.

The Castavets’ insidious encroachments start with a persistent dinner invitation. Gordon won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her brash foiling to Blackmer’s gentle, grandfatherly aura; given how he brags on his travels and she fusses over every bite that the couple eats, one would think that these senior citizens had not seen or talked to anyone for decades. The Castavets’ grand effort evokes a sad ethos as the couple returns from dinner laughing at them.

The tangle of deception starts immediately at this dinner, with Guy and Roman having a sneaky cigar-moment; multiple viewings reveal the anticipation and guilt pressed into Guy’s face. After just getting by in Yamaha commercials and small stints in no-name plays like “Nobody Loves an Albatross,” Guy is suddenly cast to play the lead in one of Broadway’s most eventful new productions. The problem? The original actor suddenly fell blind, and his understudy Guy feigns regret and sympathy while they prepare for his big moment. Newly exalted on the theatric stage, he seduces Rosemary to believe he wants to be a daddy—and soon.

Meanwhile, Rosemary cannot even enjoy a cabaret piano album, good book, or the first day of her period without Minnie or Roman coming by. Even their “baby night” is co-opted by the couple, who insist upon offering dessert as Guy and Rosemary settle into a candlelight dinner, fireplace night to start their baby making. Domineering, overbearing and at times just plain insulting, Guy practically orders Rosemary to eat the “mouse” (as Minnie calls it) with its chalky under-taste with which Rosemary is uncomfortable. Part horror film, cinema noir masterpiece, and psychological thriller, viewers should strongly feel for the patronizing and aggressive infantilizing of Rosemary into others’ wishes and schemes. She ends the night passed out.

From the couple’s pristine and glowing white bedroom to the eerie, dark mahogany Castevet apartment, Rosemary’s Baby is one of the first American films to show a graphic ring of frontally-nude elderly people; audiences had to wait for Speilberg’s Schindler’s List and its cruel depiction of the Holocaust to see it again. Doused with Christopher Komeda’s carnivalesque horn score and William A. Fraker’s lucid cinematography, the seamless and ethereal nightmare (about which Rosemary shouts “This is no dream…this is really happening!”) travels from the Sistine Chapel, to a yacht where Hutch appears calmly, to Yankee Stadium where Pope John VI delivers sacraments for Rosemary’s forced bestiality. There is a vivid humping scene, with Rosemary and Guy’s mandatory exhibitionist intercourse flanked by the elderly coven members’ gross chanting. Initially, Guy swaggers and swoons onto his petite, lithe wife who willingly relents to being restrained to the bed. He slowly transforms into a beast with prickly hairs sprouting, fingernails shooting into claws, and beady yellow eyes peering down.

A young Charles Grodin plays a bit cameo part as Dr. Hill, recommended to Rosemary by her yuppie friends who have used the obstetrician before. Of course, the Castavets have a much better idea for her: Dr. Abe Sapirstein (Ralph Bellamy). The gruff doctor is unwavering about poor Rosemary’s submission to the ideas and drinks of Minnie and Roman, as Guy submerges himself in his big moment. The film offers a valid and premonitory critique of the advent of psychology and psychoanalysis as it relates specifically to women; though she can be nauseating and exaggerated as helpless and devoted, Rosemary is an intelligent and astute woman who can’t even determine what she wants to eat or how much pain she is supposed to take during a pregnancy.

The feminist eruption of the times appear when Rosemary’s brazen and Barbarella-like young girlfriends come by for a party she insists on throwing (with “no one under 65 invited”); Guy gets the door slammed in his face, as they slap Rosemary to her senses and insist she return to Dr. Hill to extinguish her pain with traditional treatment and accept that Guy has been abusing her. As we watch Hutch fall ill after frantically wanting to meet Rosemary to pass off the book “All of Them Witches,” and Rosemary cannot even go downtown without Minnie showing up, viewers know they are in store for revelations no one wants to imagine.

Like Terrie and the stricken-blind actor, Hutch becomes a victim of satanic schemes after visiting Rosemary to express alarm over her appearance. Yet the gift of his death to Rosemary is enlightenment. Through the lone clue of “The name is an anagram” and a Scrabble board, Rosemary sees that Roman Castavet is actually Steven Marcato—son of legendary witch innovator Adrian Marcato. Fully pregnant in a sweltering 1965 July in New York City, Rosemary makes valiant but thwarted efforts to alert Dr. Sapirstein, Dr. Hill and her friend Elise to what she believes will be the eventual capture of her newborn for the use in a coven’s rituals. How sad, gleefully thrilling and cinematically compelling to witness Farrow hobbling through doctors’ offices, phone booths, and cage elevators to escape her husband and her doctor. They chase her down to treat hysteria. Of course, it’s no dream, and it is really happening – she delivers her little “Andy or Jenny” while passing out from tranquilizers, screaming for forgiveness, being held down by senior citizens and tricked into a Prozac-level daze to calm her reactions to the baby’s death.

The rather cheeky and abrupt conclusion of the film leaves much to the imagination about what Rosemary finally confronts in her child’s bassinet, once she figures out how to hide her medications and make it to the other side of an apartment with a butcher knife that will do her no good against the satiated and victorious coven celebrating in the Castavet’s home. The novel’s extended ending dialogue offers a bit more of a peek into what Rosemary plans to do as the mother of the half baby/half beast and underworld angel she had not planned on. But, Polanski leaves us with the lullaby of “La la la la,” as we watch a deranged Rosemary rocking her child’s bassinet as she instinctually gazes into a baby’s face that only a mother (or witches) could love.