Chimera is an ambitious dark sci-fi film written and directed by Maurice Haeems. A directorial debut, the film tackles heady themes and builds a chilling atmosphere of isolation and insanity against a background of bio-technology gone awry.

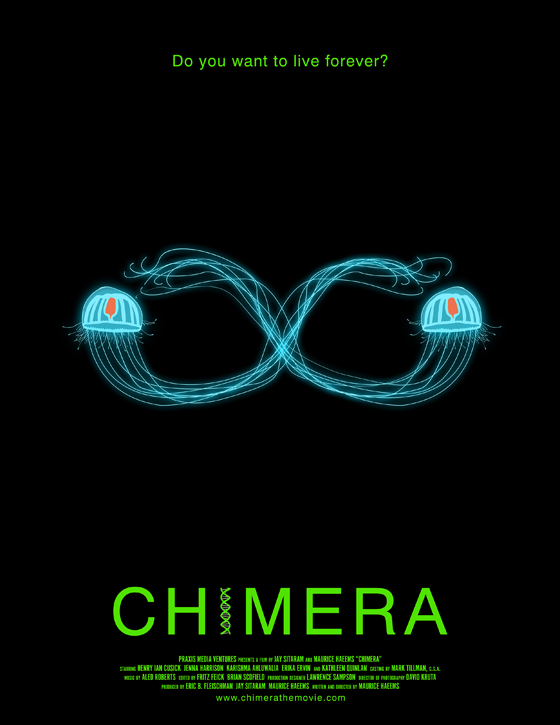

The story follows brilliant-but-troubled scientist Quint (Henry Ian Cusick) as he struggles to cure the rare genetic disorder that killed his wife and will soon kill their two children if he does not develop a cure. To do so, he attempts to unlock the genetic secrets of the effectively immortal Turritopsis jellyfish, synthesizing a unique cellular protein into human DNA and providing the recipient with phenomenal powers of regeneration. If successful, his work would not only cure his children but provide effective immortality, youth and disease resistance to anyone who received it.

Unfortunately for Quint, his research is far from complete enough to reach his goals, and his children are ticking time bombs. There’s also the matter of Masterson (Kathleen Quinlan), a frightening and mysterious rival who wants to turn his work toward her own purposes through any nefarious means necessary.

On a conceptual level, Chimera has a lot going for it. It leaves behind the high gloss and glamor often associated with these bio-tech thrillers, the type of stylings that can’t help but make the science seem attractive even as we’re meant to be repulsed by it. Quint’s story is one of isolation and a slow unravelling of sanity. In the opening sequence, we see him carrying his brain-dead wife into his isolated laboratory, hooking her up to life support more from an inability to let go than for any scientific purpose (although she does later find a purpose in one of the film’s most deeply disturbing moments).

From there, we see him grappling with her ghost; his wife is present in every moment of his work, haunting his psyche and acting as a conscience for him to rail against. We see him, too, simultaneously devoted to his children but incapable of providing them with any sense of normalcy or even love; here is a man too concerned with saving his children’s lives to spend any time making them worth living.

For all of its strengths, though, Chimera feels somewhat unfinished. Its aggressively en-media-res opening gives the impression of a sequel to a story that was not released; its tight 84 minute runtime leaves little room to unpack its ambitious story, sometimes feeling more like an extended trailer than a completed film. Many things are left to subtext that would have been more interesting if they were explored on-screen. What little we see of menacing mad-scientist Masterson is fascinating, and I would have happily taken many more scenes to unpack her villainy and the history between her character and Quint’s.

There is an issue, too, with the way Quint’s isolation forces the story to be told. As he spends much of the film alone in his laboratory, communicating only with the psychological specter of his dead wife, a lot of vital plot exposition is crammed into voice-overs. At times, the technique works well to drive home the pitiable depths of Quint’s derangement; other times, it feels like an afterthought tacked on by a script that had left few other opportunities to convey the material. It’s rare that I watch a film that I think would have worked better as a novel, but in this case I wonder if the more intimate storytelling method might have been a more natural choice for the material.

Nevertheless, there is plenty to chew on in this film. A truly Hitchcockian twist ending and a few genuinely unsettling events are guaranteed to be haunting. And perhaps most promising of all is the awareness of just how much Haeems manages to tease out in a single brief film. Given a bit more experience and opportunities to perfect his technique, and this is one writer/director who may be producing absolutely phenomenal things in the future. Keep an eye out for this one.