After my last article about haunted attractions, I got bit by the Halloween bug pretty hard. Combined with the chilly weather, I quickly found myself loading up my Netflix queue with horror movies. Subsequently, I’ve watched a lot of them over the last week, ranging from the downright terrible to the surprisingly competent. I knew better than to really expect “great,” though, which is why I was so pleasantly surprised to stumble across Dread.

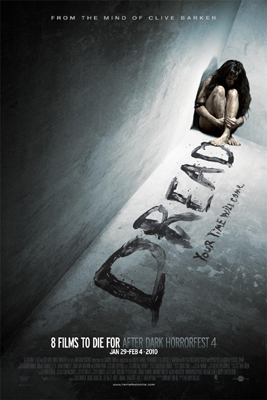

Dread was released in 2009 as part of After Dark’s 8 Films to Die For series. Written and directed by Anthony DiBlasi, the movie is adapted from a little-known Clive Barker short story of the same name. The only actor in it that you’ll probably recognize is Jackson Rathbone, better known for his role as Jasper in the Twilight films. While Rathbone holds his own, the best performance is provided by little-known actor Shaun Evans, who plays the film’s antagonist.

Truthfully, I almost removed the film from my queue without even watching it. It had a three-star rating on Netflix, and the description makes it sound very derivative and potentially ridiculous: “For a college study, a student interviews people about their darkest fears, then uses the data to methodically torment his hapless subjects.” While this is undoubtedly what the story is about, the plot is deeper, richer and much more nuanced than the description would let on. I turned it on expecting something like The Final meets Saw. What I found instead was an oddly cerebral, deeply troubling film that breaks down and reinvents the genre in surprising ways.

The film begins with Rathbone’s character, Stephen, meeting Evans’ character Quaid. We quickly learn that Stephen is a film student and Quaid is a psychology major with a somewhat obsessive interest in Nietzschian philosophy and a desire to “touch the beast” – discover the root of fear and confront it to heal those fears through catharsis. This leads to a collaborative film project where fellow students are interviewed about their fears. Not just the surface phobias, but the deep psychological scars rooted in childhood trauma.

Quaid, we realize, is carrying some deep scars of his own. As a young child, he witnessed the murder of his parents by an axe-wielding stranger, and we catch glimpses of this through flashbacks, night terrors and hallucinations. Ultimately, unsatisfied with the results of his experiment – feeling that he had not yet really gotten to touch the beast – Quaid takes it to the next level by systematically forcing people to relive their fears in progressively more sadistic ways.

There are a few things that make this film stand out from others of its genre:

– It builds momentum slowly and spends time fleshing out the characters. This is seen as a weakness by many of the people who viewed it, which explains many of the lackluster reviews on Netflix and IMDB. Every character is exquisitely crafted, making them simultaneously sympathetic and damaged – in other words, real. For once, we have a story about college students who actually act like real college students, not Hollister models.

– For a “torture porn” film, it has a very low body count and relatively little gore. This, too, is a disappointment for some fans who are accustomed to the buckets of blood from Hostel or body-horror gross-outs like The Human Centipede. Most of the really bloody scenes are reserved for Quaid’s flashbacks, while the torture scenes themselves are much more subtle and psychological. This is, for me, one of the film’s greatest strengths. Instead of blasting us with gross-out images, the filmmaker carefully and precisely chooses only a few powerful and genuinely disturbing moments.

– The film recognizes, as so few American horror movies do, that some things are worse than death. The torture implemented in the film has less to do with physical harm than with invoking genuine horror. Some of the victims essentially torture themselves after crossing a “fear event horizon” set in motion by Quaid.

Far and away, though, the most fascinating element of the plot is Quaid’s character. In torture porn movies, there’s rarely much rationale for why the sadistic killer is behaving the way he does. After all, understanding something is the first step to dealing with it, and motives and psychology have a humanizing effect on killers. Human brains are quick to find patterns or cause-and-effect in events, and few things are as unsettling for us as people who act without a rational explanation. Unfortunately, this is difficult to pull off in film, as human antagonists with no clear motive or psychological explanation often come off as fake. Creating a character that is simultaneously irrational while maintaining a sense of internally consistent motive is extremely difficult, and that’s precisely what Dread accomplishes.

While some killers are given motives – like Jigsaw in the Saw franchise – these motives often make essentially no sense or feel like a mere afterthought to hold together a string of creatively sadistic gore scenes. Quaid, on the other hand, is crafted in a way that’s much more believable.

We’re treated early on to a flashback showing the death of his parents, and images from this play and replay throughout the film in a series of nightmares and hallucinations that grow more frequent and disturbing as he stops taking his medication and pursues his darker obsessions. Interestingly, the images change in subtle ways each time we see them, and the timing of the remembered attack also shifts as his memories and hallucinations start to interact with his perceptions of the real world. This suggests that Quaid may not be an entirely reliable narrator, and it leads the perceptive viewer to wonder if there might be more to the story than ever makes it onto the screen.

Many of the negative reviewers complained about Shaun Evans’ performance, but I found it to be spot-on. We’ve come to expect certain things from our television psychopaths, and Evans sidesteps these predictable behaviors to deliver a portrait of a mentally unstable killer that seems more real and genuine than any I’ve seen in a horror film. He’s precisely the kind of mentally disturbed, baggage-toting psychology student who you can and do actually meet if you spend enough time on a college campus. By turns charming and short-tempered, manipulative and vulnerable, he’s clearly damaged and seeking to solve that inner torment; when psychology doesn’t work, he turns to nihilism.

Indeed, much of the discomfort from viewers seems rooted in the film’s realism, from the unexpectedly swift and brutal violence to the subdued performances from its characters. We often watch the so-called torture porn movies with an almost gleeful attitude, deriving a twisted sort of pleasure from the blood as it’s spilled on the screen. You won’t get that sort of titillation from Dread. The film is dark, relentless and bleak, and it crawls under your skin and haunts you with its troubling realism.