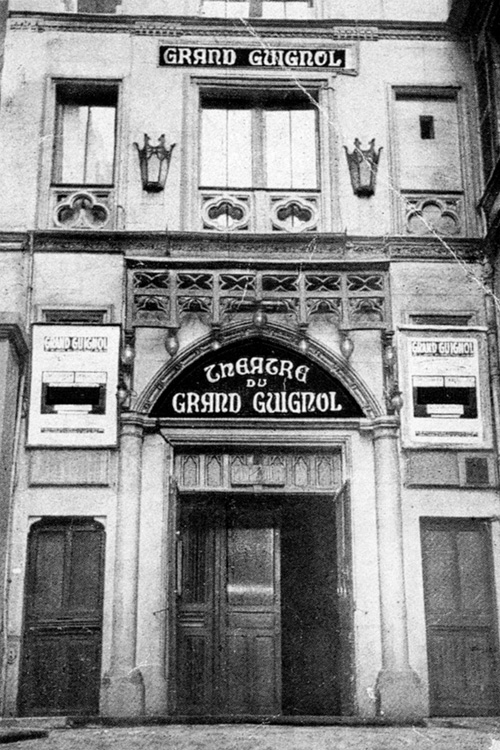

Grand Guignol is a byword for shockingly grisly horror. Blood, guts, vomit, and other secretions—these were the trademarks of the dirty, little theatre in the Pigalle section of Paris. From 1897 until 1962, Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol ran millions of plays, most of which were one-act productions that emphasized cruelty. Although performances of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, John Webster’s The White Devil, and other Elizabethan and Jacobean revenge dramas did occur, most Grand Guignol productions were in-house originals. The most prolific of these scribes was Andre de Lorde, a librarian at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal whose 150 plays earned him the nickname the “Prince of Fear.” De Lorde’s plays tended to emphasize psychosis, madness, and extreme perversions. Brutal death scenes inside of madhouses became his stock and trade, and for most, de Lorde’s version of realistic terror is the defining characteristic of Grand Guignol.

Maurice Level, real name Jeanne Mareteux-Level, was de Lorde’s chief competitor. Like de Lorde, Level’s plays are naturalistic and typically avoid supernatural elements. Unlike de Lorde, Level’s work is notable for its excessive use of irony. Sick, twisted irony would be more appropriate to say. Also, rather than exclusively write plays, Level actually constructed short and claustrophobic stories that would eventually leave France and wind up in the pages of Weird Tales. This is where Lovecraft found him, and notably, Level is the only Grand Guignol writer explicitly named in Lovecraft’s “Supernatural Horror in Literature.” Although Lovecraft declares that “the French genius is more naturally suited to this dark realism than to the suggestion of the unseen,” he nevertheless applauds Level and the other scribes of the Grand Guignol.

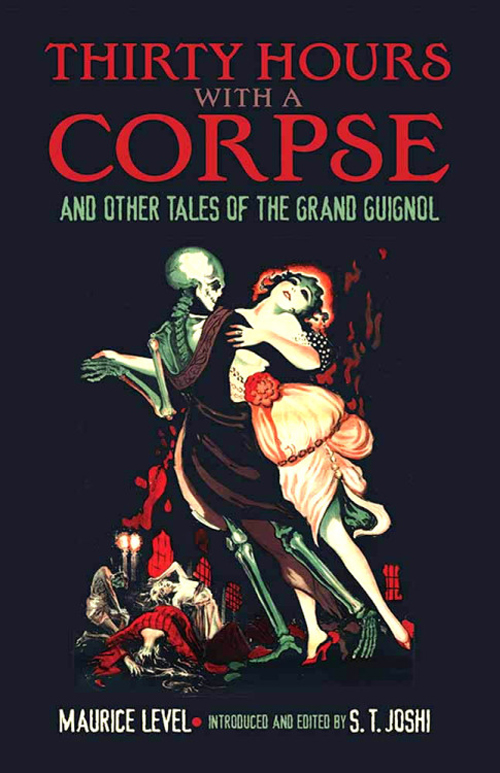

Today, a new appreciation for Level may be emerging. Just this month, Dover Publications, who are also in the middle of rereleasing the work of William Seabrook, the adventure journalist who helped to popularize zombies in the United States, released Thirty Hours With a Corpse, a collection of Level’s best short stories. Edited and introduced by the world’s foremost Lovecraft scholar, S.T. Joshi, Thirty Hours With a Corpse asserts that Level’s oeuvre, with its “relentless emphasis on crime, hate, vengeance and their psychological effects,” is a “distinctive contribution to literature.” This isn’t just hyperbole on Joshi’s part, either. After consuming Thirty Hours With a Corpse, it’s now possible to see the distinct imprint of Level on some strains of contemporary horror fiction. Furthermore, much of the work produced by E.C. Comics during the early 1950s bears the unmistakable influence of Level. (Indeed, Joshi points out in the introduction that Level’s play Le Baiser dans la nuit was made into an uncredited adaptation by the infamous comic book publisher.)

This is not to say that every story in Thirty Hours with a Corpse is a winner. Some of the later entries, especially those composed during the First World War, are neither frightening nor particularly good. Although it’s clear that Level was an ardent patriot, one has to wonder why such stories as “The Spirit of Alsace” (a sort of espionage tale), “At the Movies” (which contains Level’s trademark irony, but without grotesque horror), and the touching “The Little Soldier” were even included at all.

Elsewhere, Level does provide the type of horror one would expect from the Grand Guignol. In “The Last Kiss,” a blind man with a face scared by vitriol (sulfuric acid) decides to turn the tables on his lover and make her like him. In “A Maniac,” Level produces a ravenous flaneur who walks around Paris looking for different forms of death. When he learns that a stunt rider uses his body as a fixed point in order to steady himself during his dangerous performances, the maniac decides to shift his body at the worst time. The titular story, which is the collection’s longest at almost twenty pages, is a precursor to Patrick Hamilton’s Grand Guignol-inspired play Rope and follows the machinations of two broke university students as they try to escape Paris with a woman’s corpse in a large trunk.

Besides irony and gritty depictions of human depravity, certain other themes populate this book. For one, illegitimate children usually exist as either murderers or as the reason for murders. Adultery is also common. But above all else, Thirty Hours With a Corpse exposes Level’s discomfort with sedation, for stories like “Under Chloroform” and “Under Ether” take the Grand Guignol interest in highly-personal horror to the extreme.

All told, Thirty Hours With a Corpse offers not only a fine introduction to the Grand Guignol style, but it also gives readers a chance to praise the idiosyncratic style of one of the theatre’s foremost stylists. Level’s stories are taut thrillers that balance the line between crime and horror. As a writer, Level produces an economy of style that is stripped of horror’s usual garishness. Modern readers will certainly enjoy this workman approach, while most horror fans should value this collection overall.

Thirty Hours With a Corpse is currently available from Dover Publications.