“This island does not want us here. Before this beacon was built, she took hundreds of lives. Perhaps she is still hungry.” –Thomas Griffiths

The sea is a harsh and unyielding mistress. Those who work her can testify that she doesn’t give an inch when you make her your home. You can see the proof of that even in a modern reality-TV show like Deadliest Catch. Now think of how hard a sea-bound life was in the days before steel ships, GPS, electric lights and other modern comforts.

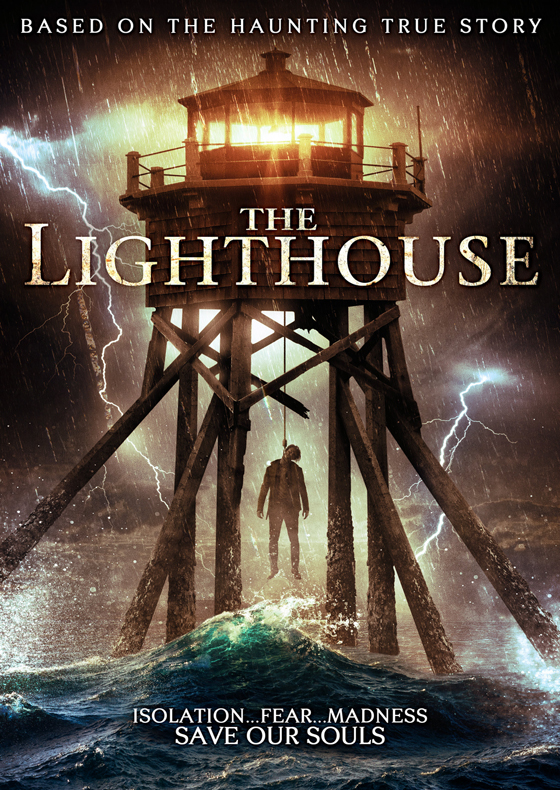

There are many grim tales of the deep waters of the world–tales of ghosts, monsters and devils–but also stories of human madness and despair. Director Chris Crow’s The Lighthouse tells a true story of just how bleak and unforgiving the sea can be. A story of how it can prey on a man’s mind and strip it bare.

Well, by now, you have the idea that The Lighthouse is not exactly the feel-good story of the summer. In my lifetime, I’ve watched an inordinate amount of grim and dark movies. This 2016 story ranks with the most relentless. There’s not one chuckle or smile to be found here, no fuzzy nostalgia for a life on the sea. It is the story of Smalls Island, its lonely lighthouse and the terrible isolation that clung to it like barnacles to the keel of a weathered old sailing ship.

It’s a story as bare and simple as the rocks of Smalls Island itself. I won’t reveal the ultimate spoilers of what happened at the lighthouse, but you can read the details of the real-life incident here. It was something so terrible that the rules governing lighthouses were permanently changed following the occurrence.

The Lighthouse is a Welsh movie and it is full of the dour nature of the Welsh themselves. That’s a culture known for hard work and a grim fatalism. Whether it’s working in the dark bowels of a coal mine or the flat grey expanse of the North Sea, the Welsh have never been afraid to work hard in the most dangerous of professions.

The year is 1801 and a new two-man shift is needed to work the lonely Smalls Island lighthouse. Smalls Island is a tiny, unforgiving outcrop of rock about 25 miles out in the Irish Sea. It is an utterly isolated spot with no sight of land. Just miles of cold grey waves in every direction. It is vital that the beacon keeps shining at all times because the surrounding shoals have taken a terrible toll in lives down through the ages.

The Smalls Island lighthouse is not what we think of today when lighthouses come to mind. We envision sturdy stone structures with steel railings and large glass panels that are strongly reinforced. Nothing like that existed on Smalls in 1801. The lighthouse there is a rickety wooden structure, precariously reinforced against the bare rock. How this thing was able to withstand the rage of ocean storms is a mystery. The ledges around the beacon are small and look utterly unsafe. On the inside, the furnishings are as dour and cheerless as an open grave. This is the environment that the two-man crews had to work in for months at a time.

The latest two men chosen to work a shift at the lighthouse are Thomas Griffiths and Thomas Howell. We get an inkling of just how opposite and unlike each other these men are when we are introduced to them. Our first sight of Griffiths is a bare knuckle brawl in some dingy warehouse. This is a man who has been fighting all his life but not always winning. Some enemies can’t be beaten with fists. In contrast, our first look at Thomas Howell sees him intently praying and reading from his bible. In addition to the usual prayers, he recites the names of six men. Howell is a man desperately trying to find God for reasons which later become clearer.

When Griffiths and Howell are rowed out to Smalls to begin their lonely shift, they say as little as possible to each other. There’s no polite camaraderie or attempt at levity. Howell seems to be widely disliked. When they reach the island, the previous two lighthouse keepers react to their replacements with scorn. One spits at Howell’s feet. You can sense these men have been ground down by their chores and are relieved that their time on the island is done.

During the entire movie, we never really get a good look at the sun. Days are at best flat and grey. At worst, during the frequent terrible storms, they are almost indistinguishable from night. The film-makers capture this monochrome limbo well. Nothing breaks up the horizon…no sign of land, no ships, nothing. Such a purgatory virtually demands grimness and stillness from those exposed to it.

The men are not there long when storms roll in. At first they are squalls, which are frequent and expected. But they increase in fury and intensity. Soon it becomes evident that the island is dead center of a monstrous, unceasing storm. “I’ve never seen its like, never,” mutters Griffiths. No ship passes their sight, but the beacon must continue to be lit, no matter how bad the weather is. The work is dangerous and brutal and the isolation is total.

Weeks roll by and the storm does not lessen its grip. Inside the lighthouse, the men are at each other’s throats. Griffiths is full of contempt for Howell’s praying and bible reading, which seem as endless as the storm. “He does not hear you!” he rages. “He does not care!” We learn the reason for Griffiths’ fatalism and hatred of God. Consumption took his wife and young daughter. His life since then has been bleak.

We also find out more of Howell’s past. It seems that during a previous sea assignment, he fell asleep during a critical watch, leading to the deaths of six men. It is the names of these men that come up during his constant prayers. Guilt has consumed Howell’s life. He considers his current stint on Smalls as part of his punishment.

It’s pretty obvious that in the time the movie takes place, the lighthouse employers couldn’t care less about the psychological well-being of their workers. Nor do they care to profile the men they choose. Otherwise, they would have easily discovered what a bad match Griffiths and Howell are for each other. Just how bad only becomes evident by the end of the movie.

At one point, Griffiths finds a dusty old box that has been hidden in the lighthouse since the very first days it was open. It contains bottles of liquor and a gun. “What is it for?” asks Howell. “Mercy,” replies Griffiths grimly.

The liquor loosens all inhibitions in the men. At first they come to blows but eventually a kind of hopeless acceptance sinks in and they begin to reveal the darkness of their pasts. But the storm is relentless. And then, while working outside on the beacon during the raging gale, something awful happens. And what had already been a grim movie now turns into unbearable madness and morbidity.

Exactly what happens, you will need to watch the film to find out. Or read about the actual Smalls Island incident, which the movie very faithfully records. Eventually, help does arrive at the island, but what they find is unnerving and helps to rewrite all rules and regulations regarding lighthouses in the British Isles. Construction of stone lighthouses begins and three-man crews are assigned to them and checked with more regularity. Those regulations stay in place until 1980, when the lighthouses finally become fully automated.

The Lighthouse is a movie at odds with all aspects of modern filmmaking. You would never see something like this at the multiplex. It starts very quietly, almost motionlessly, and gradually picks up steam until it becomes the definition of horror and madness. Is there a real haunting or all the ghosts in the mind? That’s for the viewer to decide.

At no point did I feel I was watching actors in a movie. The settings, the costumes and the ambience are all so much like Wales circa 1801 that you feel like you are looking through a window in time to witness something terrible. One downfall is that the lighting is also faithful to the period. The interior of the lighthouse is so dimly lit by a few candles that the interior scenes are often muddy and hard to make out. The storm scenes are breathtakingly real and you wonder how many of them were done without taking place in an actual hurricane.

The success of a claustrophobic film like this lies heavily on the shoulders of the principal actors. Two characters dominate the movie and so the actors in those parts must be excellent. As Thomas Griffiths, Mark Lewis Jones is gruff, hard bitten and real…the very picture of a tough Welsh seafaring man. In many ways, Griffiths has given up on life, but he is such a natural fighter that it seems he is ready to brawl with the storm itself. As Howell, Michael Jibson takes a much different approach. Meek and reserved, he does his fighting through endless prayer. But we sense something is not quite right with Howell and in the last third of the picture, Jibson transforms the character into a man battling insanity…and losing. Incidentally, Jibson co-wrote the movie and had a hand in producing it.

The Lighthouse is a welcome deviation from most modern horrors, one rooted in a dark reality. If you’re looking for something different than just entertainment and distraction, I highly recommend it. But you won’t be whistling a happy tune and dancing a jig when this one is done.