It’s become commonplace to identify Japan with all things weird. From tentacle porn to wearable robotic cat tails for humans, the Land of the Rising Sun has birthed some seriously strange cultural artifacts. Whether or not Japan has always been like this is a question for someone better equipped than I am, but as a dabbler in all things Japanese culture, I do appreciate that country’s emphasis on the bizarre and grotesque. But sometimes there’s too much saturation, and even though I do enjoy Hideshi Hino and Takashi Miike, sometimes even I need a break.

Mystery and suggestion are always good counterweights to extreme gore, and as such the cozy company of Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers provide a nice respite. Then again, the traditional British novel from the interwar years verges on the saccharine, and we all know what too much sugar does to our blood.

This then is the point where I start looking for a middle ground. On the one hand, blood and violence are always welcomed house guests (but they always leave a stinking mess on my carpet), but on the other hand a little bit of artistry, shadow, and light never hurt anyone. Enter Edogawa Rampo—the Japanese Poe. This isn’t mere hyperbole either, for Tarō Hirai (or Hirai Tarō in the Japanese formation) chose the pseudonym “Edogawa Rampo” because, if said quickly enough, it sounds like “Edgar Allan Poe.” Beyond that, Rampo’s short stories, the best of which were written and published in the 1920s and 1930s, followed the shadow of Poe in that they focused on the themes of unreliability, madness, and sadomasochism. Or, to put it in Japanese, ero guro nansensu—eroticism, grotesquerie, and the nonsensical.

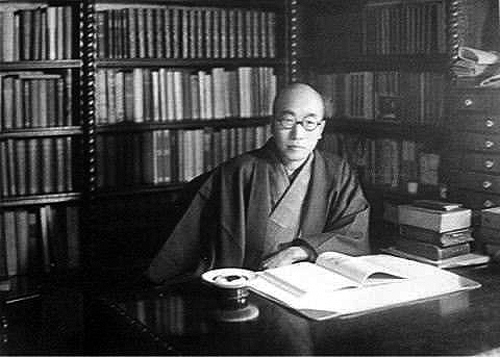

In order to understand Rampo’s darkness, we must first understand the man and his times. Born in the Mie Prefecture city of Nabari in 1894, Rampo’s illustrious family could boast of samurai elders and other members of the Edo period nobility. This tradition of success touched Rampo as well, and at age seventeen he enrolled at the private Waseda University in Tokyo. While there he majored in economics before graduating in 1916. After that, Rampo worked six years as a “clerk, accountant, salesman, and editor, sometimes also pulling a cart as an itinerant soba vendor.”[1] Even though Rampo was a ravenous consumer of foreign detective and mystery stories, he did not publish his first short story until 1923—a year he spent mostly unemployed in Osaka.

Rampo’s first short story, “The Two-Sen Copper Coin” (“Ni-sen dōka”), appeared alongside such luminaries as G.K. Chesterton and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in the pages of Shin Seinen (New Youth)—a popular magazine aimed at a young audience. In light of Rampo’s later work, his debut in an adolescent magazine would seem like some kind of twisted joke, but at this point in his career Rampo wrote straightforward mysteries in the vein of Sherlock Holmes and M. Dupin, and in fact his story “One Ticket” (“Ichimai no kippu”) has often been compared to Poe’s “The Purloined Letter.”

Then, after publishing his first collection of short stories in 1925, Rampo founded the Association of Lovers of Detectives, which, after World War II, would become the highly influential Mystery Writers of Japan. 1925 would also prove to be a vanguard year for Rampo in other aspects as well, for in that year he published “Case of the Murder on D-Slope” (“D-zaka no satsujin jiken”). “Case of the Murder on D-Slope” deals with the murder of a woman in the course of vicious and sadistic extramarital affair—a subject matter that was far from mainstream in Japanese society at the time. Rampo’s willingness to stretch the bounds of decency was further evidenced by two other stories from 1925: “The Stalker in the Attic” (“Yane-ura no Sanposha”), which at one point has a man pouring poison into a neighbor’s throat from the floor above, and “The Human Chair” (“Ningen Isu”), which is undoubtedly Rampo’s most famous story outside of Japan.

“The Human Chair” tells of a beautiful young author named Yoshiko. Yoshiko is quite popular, and as a result she receives quite a lot of daily correspondence from admirers and aspiring authors looking for advice. One such letter arrives on a day when Yoshiko’s husband has left her alone in the house. The letter writer claims to be a master chair maker who suffers from a hideously disfigured face. Due to his ugliness, the unnamed chair maker not only has poorly developed social skills, but his idea of sexual intimacy revolves almost solely around voyeurism.

One day, after completing a large and luxurious chair for a newly built hotel, the chair maker, realizing that he cannot part with his masterpiece, realigns the chair’s insides in order to allow him to live inside of the chair without detection. He does not have much room and because of the heat he must sit naked inside of the chair.

When the chair is transported to the hotel’s lobby, the chair maker realizes that the chair gives him the perfect means to commit robbery. During the night, the chair maker slinks out and robs the many foreign guests, and then when the morning comes he retreats back to his unsuspecting hiding place. This plan works well for a while, but it is ultimately curtailed because the chair maker begins to fall in love with the various women who sit on him. His close proximity to them means that he can all but caress them, and in certain passages, the chair maker’s descriptions of the women verges on softcore smut.

Then, when the hotel changes management, the large and expensive chair is eventually auctioned off to a Japanese political official. This official has a lovely young wife who likes to read for hours at a time whilst sitting on the chair and because of this the chair maker has developed a strong infatuation with the official’s wife. His love is so strong that he slips out one night and writes her a letter that desperately asks her to look upon his ugly face. Realizing that she is holding the very same letter, Yoshiko starts to hear someone else in the house with her.

I won’t reveal the ending, but I will tell you that when I taught this story to my students last year, their faces collectively took on the visage of Butt-head—lips pulled back, eyes squinted inwards in horror, and open mouths that breathed heavily. It was a sight and it spoke to the power that Rampo’s words and images still had despite the many decades between 1925 and 2013.

Shamefully, few American students get this type of experience and even more have never heard of Edogawa Rampo. The Japanese Poe has always been more popular in Asia than in North America, and despite the globalization of the Internet, English language translations of Rampo’s works and dubbed versions of filmed Rampo adaptations are hard to come by. As such Rampo remains a collector’s item for many, and of those collectors, most are mystery enthusiasts with no hope for a cure. I am one of those sick legion, and from the depths of illness I can tell you where it all went wrong.

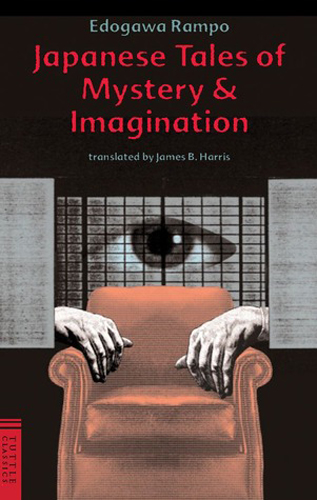

For those interested in tasting Rampo’s poison, Japanese Tales of Mystery and Imagination is a good place to start. That particular book, which contains nine of Rampo’s best stories, perfectly captures the young Rampo and the Tokyo of the 1920s, which writer Ian Buruma compares to the wanton, hedonistic, and artistically active Weimar Berlin in Inventing Japan, 1853-1964. In Japanese Tales of Mystery and Imagination, be on the lookout not only for “The Human Chair,” but also “The Caterpillar”–a story so demoralizing in its depiction of a quadriplegic army lieutenant that the Japanese government banned the story not long after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident caused the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. This brush with the censors partially weakened Rampo’s artistic daring, and during the Second World War he primarily focused his energies on creating patriotic stories set against the backdrop of the Japanese home front.

After the war, Rampo spent most of his time promoting other Japanese mystery writers, as well as promoting mystery literature in general with his many scholarly studies. When he died in 1965, Rampo was celebrated as one of the greatest stylists to ever come out of Japan. That’s high praise, but Rampo was and continues to be worth every syllable.

[1] Marling, William. “Vision and Putrescence: Edogawa Rampo Rereading Edgar Allan Poe.” Poe Studies/Dark Romanticism, Winter 2003.