Amazingly, ever since the publication of A Study in Scarlet in 1887, the “Great Detective,” Sherlock Holmes, and his assistant/Boswell-like biographer Dr. John H. Watson have enthralled readers with their tales of ratiocination (to lift a phrase from Edgar Allan Poe – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s inspiration) and physical derring-do. After all, who can forget the ingenious murder device in The Adventure of the Copper Beeches or Holmes’s masterful deduction in The Problem of Thor Bridge.

Of course the other appeal of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s creations is their easy adaptability. Beginning with the American stage actor William Gillette (who changed the literary Holmes’s simple black briar pipe into a curved meerschaum one because it allowed him to deliver his lines more clearly), the figures of Holmes (and Watson) has undergone numerous facelifts and shifts. Famously, Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce played the detective duo in fourteen films produced between 1939 and 1946. Rather than use Rathbone’s hawkish and aristocratic Holmes and Bruce’s buffoonish and ineffectual Watson for period piece cases set in the Victorian era, Universal Studios (which oversaw the production and release of the last twelve films) placed Holmes and Watson in the contemporary milieu of the Second War World. As such, films like Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror (1942) and Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (1943) pit the bulldog-ish Brits, Holmes and Watson, against the nefarious machinations of secret Nazi organizations, one of which is headed by Professor Moriarty, the arch villain who first made his appearance in 1893’s The Final Problem.

Even more recently, the BBC’s Sherlock series, which stars Benedict Cumberbatch in the title role and Martin Freeman as Dr. Watson, has brought Conan Doyle’s creations to the twenty-first century. Accordingly, Holmes and Watson must duke it out with serial killers, international terrorists, and information thieves who criminally navigate and hack into the web. Added to this new cast of antagonists are discussions about the chemical imbalances of Holmes (does he have ADHD? or is he autistic?) and the sexual implications of two adult men sharing a flat together (it’s hard to find an episode that does not have other characters questioning whether or not Holmes and Watson are lovers).

While all of these periodic changes seem unique to the non-literary Holmes, the original canon of the Holmes and Watson tales, which ran from 1887 to 1927, contains plenty of re-imaginings and huge shifts. After his “death” at the Reichenbach Falls in The Final Problem, Holmes would not return to the world’s readers until 1902’s brilliant The Hound of the Baskervilles. Even then, Conan Doyle (who hated the character because it took all the attention away from his historical novels) made sure that the events at Baskerville Hall occurred before Holmes and Moriarty plunged into the cold Swiss waters.

Then, in 1903, Holmes returned for good in The Adventure of the Empty House. Still, the twentieth century Holmes was a different man – no longer a bohemian, no longer a recreational drug user, and no longer a “consulting detective” with a superior attitude towards British authorities. As the world built up to the “Guns of August,” Holmes and Watson took on cases with international importance, from the various espionage intrigues of The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans and His Last Bow to the highly political thrillers of The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge and The Adventure of the Red Circle. Typically, the Holmes that many in Hollywood like to reuse is the latter Holmes – the gentleman spy who is willing to become the entirety of British Intelligence in order to halt foreign-born and domestic threats to the crown and country.

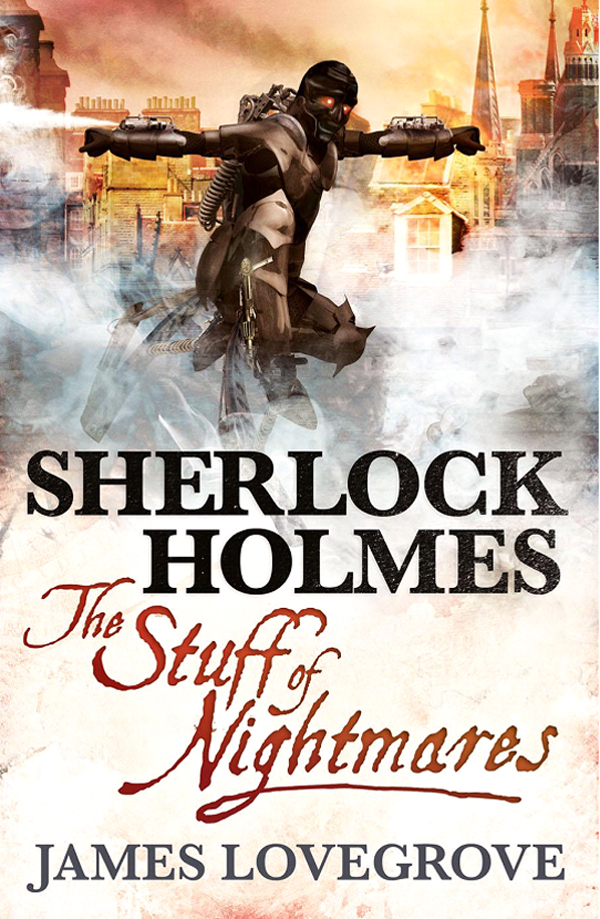

This version of Holmes is the Sherlock Holmes one finds in James Lovegrove’s Sherlock Holmes – The Stuff of Nightmares. Set in 1890 but written by an older Dr. Watson reflecting back from the vantage point of the tattered post-World War I world, Sherlock Holmes – The Stuff of Nightmares deals with a series of bombing outrages that eventually threaten Queen Victoria. The book opens with one such bombing occurring at Waterloo Station. Dr. Watson just so happens to be returning from a brief holiday with his wife when all hell breaks loose. This bombing not only sets the novel’s action and narrative trajectory in motion, but it lets you know right away that Sherlock Holmes – The Stuff of Nightmares will not be a cozy, locked room mystery.

Along with these anarchistic, possibly Fenian-organized dynamite attacks, London’s East End is haunted by a mysterious figure named Baron Cauchemar. One part Spring-heeled Jack and one part Jack the Ripper, Baron Cauchemar initially looks like the man responsible for the bombings. Suspicions turn however after Holmes and Watson are privy to witnessing Baron Cauchemar’s destruction of a sex slave ring involving women imported from China. Astoundingly, Baron Cauchemar is described as a mechanical man, or rather a sort of steampunk Batman. Rather than an evil monster, Baron Cauchemar is a masked vigilante who becomes an ally to Holmes and Watson.

Their target is one Vicomte de Villegrand, a debauched French aristocrat who heads Les Hériteurs de Chauvin, a Bonapartist organization of right-wing radicals who want to see the map painted a French blue. Named after the semi-mythical French solider Nicolas Chauvin who fought honorably for both the First Republic and Emperor Napoleon, Les Hériteurs de Chauvin seem like the fellows who just a few years later will help to send Captain Alfred Dreyfus to Devil’s Island, plus their ideology is eerily reminiscent of the still later National Socialists (Hitler is alluded to at the novel’s end) and their ideological brethren in the Organisation de l’armée secrète.

Besides seeking the end of this political terrorism, Baron Cauchemar has a personal reason for interrupting the Vicomte’s plans. While they both lived in Paris as part of the Les Hériteurs de Chauvin, Baron Cauchemar (or rather the Englishman Fred Tilling) was a Jules Verne-inspired creator of mechanical wonders and advanced machinery. Tilling was also smitten with a young Frenchwoman named Delphine. Unfortunately for Tilling, the Vicomte fancied Delphine too, and during a passage that would have been too sexually explicit for the Victorian era, the Vicomte forcibly deflowers Delphine, and as a result kills her. The gratuity of this scene is certainly modern, and it reveals the fact that Sherlock Holmes – The Stuff of Nightmares was not written during the age of gaslight and hansom cabs.

Other moments of twenty-first century entertainment are present during the book’s climax, which pits two steampunk adversaries against each other. In one corner there is Baron Cauchemar, and in the other is the Duc En Fer, the Vicomte’s train which, with the pull of a lever, can become a hulking, Transformers-like fighting engine. This big battle is the kookiest moment in the entire novel, and its orchestration seems ripped from fanboy imaginations.

Despite this moment, Sherlock Holmes – The Stuff of Nightmares is an excellent read that constantly refers back to the original stories and novels, as well as to other Conan Doyle creations (Professor Challenger, for instance). James Lovegrove, the New York Times best-selling author behind The Age of Odin, writes science fiction and historical adventures with a deep sense of literary acumen and élan. Sherlock Holmes – The Stuff of Nightmares is a fast read with many short chapters, but it is also a very intelligent, well-crafted novel that does justice to the characters, both Conan Doyle’s and Lovegrove’s own. More importantly, Lovegrove’s latest novel showcases the timelessness of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson by placing them in a case that would have mattered in the late nineteenth century, and one that also has ramifications in our current global climate.

Sherlock Holmes – The Stuff of Nightmares is currently available as an ebook and paperback from Titan Books.