Death is an incident producing clay. Use it, mould it, learn from it. ~John Gilling (1912-1985)

When people speak of Hammer Film Productions, they usually speak with a resounding sense of awe. This is done with good reason, for the London-based studio helped to keep traditional and even gothic horror alive during the science fiction-dominated 1950s and the socially turbulent 1960s. With plenty of red plasma and enough heaving breasts to make the inimitable Russ Meyer pant, Hammer helped to cultivate a new vision of terror – a vision that not only embraced technicolor and the postwar trend towards sexual openness, but also a financially prudent and regimented filming schedule. From the late 1950s until the mid-1970s, Hammer was the shinning apex of cinematic horror.

The reasons for this position are many, including the exquisite and recognizable set designs and the praiseworthy color photography. One can also not overlook the enormous amount of talent that worked at the company’s legendary Bray Studios in Berkshire. Terence Fisher, one of the world’s finest horror directors, made his name under the Hammer banner, whilst two actors – the gentlemanly Peter Cushing and the malevolent Christopher Lee – helped Hammer to become synonymous with horror. It is understandable why most people gravitate towards Fisher, Cushing, and Lee whenever the history of Hammer comes up. It is just as understandable why most people (horror film buffs included) don’t immediately recognize the name of John Gilling.

For all intents and purposes, Gilling was a second-tier talent. Throughout his many years with Hammer, Gilling was primarily a journeyman screenwriter and sometime director who was best known for his action-filled costume dramas and his many crime films. Around the back lots of Bray, Gilling was known as a humorless man with a quick temper and a long-held grudge against Anthony “Tony” Hinds, the son of William Hinds, Hammer’s founder. Oliver Reed, the famous “tough guy” actor who was an even more famous drunk, once said of Gilling: “People loathed John, because they said he was a bully. He was brash – gruff…But I liked him.” [1]

Gilling’s crabby disposition often made him a hard director to work with and an even easier screenwriter to “screw over.” Despite this, Gilling somehow managed to be the main creative force behind three of Hammer’s best films from the 1960s – The Gorgon from 1964 and the so-called “Cornish duo” of The Plague of the Zombies and The Reptile (both from 1966). While these three films are often overlooked in favor of Hammer’s more literary films (i.e., those horror films based on already well-known literary monsters), they nevertheless present that unique Hammer feel and quality that so many viewers love. Furthermore, these three films have all entered into that deliciously decadent realm of the cult film. Much of this reality is due in no small part to the guiding hand of Gilling – a creator who favored action and style over loquacious scripts and Hammer’s penchant for melodrama. Gilling deserves to be recognized as one of Hammer’s best stylists, and his name should be far more common in the mouths of horror aficionados than it currently is.

Act I: The Gorgon

By the mid-1960s, Hammer was a worldwide sensation. The popularity of such films as 1958’s Dracula (released in the United States as The Horror of Dracula in order to avoid confusion with Tod Browning’s 1931 expressionist masterpiece) and 1957’s The Curse of Frankenstein had helped Hammer to become a household name for all things macabre. Unfortunately, by the early 1960s, a slew of sub-par films had helped to weaken the studio’s reputation, along with an increasingly shrewd circle of critics who were starting to recognize Hammer’s greatest weakness – repetition.

In 1962, one film managed to succinctly capture Hammer’s decline on celluloid. This film was The Phantom of the Opera, Hammer’s take on Gaston Leroux’s excessively popular novel from 1911. Although it was directed by Fisher and it contained the studio’s trademark gorgeous color photography, The Phantom of the Opera was a commercial failure. The fallout from the film pushed Fisher, Hammer’s best director, away from his typical fare, leading the auteur to film with other studios and in other countries. In the mere two years between The Phantom of the Opera and The Gorgon, the typically prolific Fisher only managed to make two films – Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace and The Horror of It All. While The Horror of It All was a campy production right from the get-go (its star after all was the wholesome American singer Pat Boone), Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace had all the right ingredients for a worthwhile picture. Not only did it star Christopher Lee in the role of the “Great Detective,” but it also featured a script by Curt Sidomak, the novelist responsible for Donovan’s Brain (1942) and the screenwriter behind The Wolf Man (1941).

Inevitably, the film’s West German-French-Italian co-production made things confusing, if not downright impossible. First of all, Artur Brauner, the film’s producer, initially wanted the film to be tied in with the then popular world of the krimi, the West German film genre that was based on the interwar era crime novels of Edgar Wallace. Unfortunately for Brauner, the estate of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle objected to this, thus forcing a reshoot of the entire film. Fisher was ultimately left with a lackluster film, and both he and Lee were unhappy with the finished product.

By 1964, Fisher made his way back to Hammer in order to film The Gorgon. In many ways, The Gorgon is a true rarity in the Hammer oeuvre. Not only is it one of the company’s few films that is not based (however loosely) on a novel, but it is also one of the rare occurrences wherein Lee and Cushing play against their usual typecasting. In The Gorgon, Cushing plays the film’s villain – the secretive and possessive Dr. Namaroff. While Cushing plays a rare villain in The Gorgon (or at least a villain not named Frankenstein), Lee plays the film’s hero – the virile and brave Professor Karl Meister of Leipzig University. The film also breaks with Hammer’s tradition in that its supernatural entity comes from Greek mythology – a cultural well that Hammer rarely tapped.

The Gorgon tells the tale of the haunted village of Vandorf, which, like Klausenberg and Karlsbad, is yet another one of Fisher’s mysterious and fictitious Central European locales. While Klausenberg and Karlsbad have to deal with the nefarious dealings of Count Dracula, the residents of Vandorf are plagued by the spirit of Megaera, one of the three gorgon sisters of Greek legend. How an ancient Greek monster managed to wind up in what seems to be Germany is rather incredible, especially considering that even during the Hellenic age, Germany was a cultural backwater with non-existent ties to the Greek world. The importance of location in The Gorgon has less to do with actual history and more to do with Fisher’s (and Hammer’s) mythologizing of a fabled Mitteleuropa, the dark and enigmatic core of German Romanticism and the breeding ground for such writers as Hanns Heinz Ewers and Franz Kafka. Much like the later “Cornish duo,” The Gorgon has an analogue in Kiss of the Vampire, Don Sharp’s 1963 film for Hammer which is set in Bavaria in 1910 – a same year as the action occurring in The Gorgon.

Besides location, The Gorgon also shares with other Hammer productions the common motif of the prologue opening. In The Gorgon, the story begins with two lovers – the artist Bruno Heitz (played by Jeremy Longhurst) and his model Sascha Cass (played by Toni Gilpin). After Sascha reveals to Bruno that she is carrying his child, Bruno stalks out into the night in order to confront Sascha’s father about the upcoming birth. Sascha soon begins to follow Bruno, but her footfalls are slowed by the shadow of Castle Borski, yet another one of Hammer’s many creepy mountain castles. When she nears a roadside crucifix (which was probably taken from the set of one of Hammer’s many Dracula films), Sascha begins to hear siren-like singing. Just as James Bernard’s music builds, the singing gives way to Sascha’s petrified screams. We, the viewers, cannot see what she is frightened of, but we do get to watch as small, grayish bubbles begin to erupt on her forehead.

After a shot of clouds swarming over a full moon, we are taken to the Vandorf Medical Institution, which is headed by Doctor Namaroff. Namaroff is interrupted in his laboratory by his lovely assistant Carla Hoffman (played by Barbara Shelley), who has come to inform him that Inspector Kanof (played by Patrick Troughton, who was not only the Second Doctor in the Doctor Who franchise, but who was also the haunted Father Brennan in Richard Donner’s The Omen) would like to see him. The Pickelhaube-wearing Kanof brings in the dead body of Sascha, who is the seventh murder victim in the last five years. When Namaroff pulls back the sheet covering Sascha’s body, it is revealed that she has been entirely turned to stone, almost as if a sculpture has been substituted in lieu of a corpse.

From here, the film transitions to a court inquiry wherein Bruno Heitz, who committed suicide after the death of Sascha, is blamed for the murder. His father, Professor Jules Heitz of Leipzig University (played by Michael Goodliffe) does not believe the court’s verdict, and furthermore, he accuses Namaroff of knowingly covering up the unsolved murders. After privately accusing Namaroff and surviving a local gang’s attempt to drive him away from Vandorf, Professor Heitz researches the possibility that the Gorgon Megaera (who in Greek mythology was one of the Furies/Eumenides, not a gorgon) was responsible for the village’s numerous deaths. While working late one night, he hears the same a siren-like call and decides to follow it to the ruined Castle Borski (which has an interior that bears a striking resemblance to Dracula’s castle). While there, Professor Heitz encounters a shadowy horror which slowly begins to turn him to stone. Before succumbing to his horrible death, Professor Heitz writes a three-page letter to his son at Leipzig University.

The death of Professor Heitz is what truly begins the film’s action. The term “action” must be applied loosely here, for unlike many Hammer films, The Gorgon is talkative, not overly action-packed, and feels slower than its ninety-plus minutes would lead you to believe. The film is mostly a melodrama parading around as a mystery. There is also a love triangle element involving Namaroff, Carla, and Paul Heitz (played by Richard Pasco). There are only two moments of actual suspense in film: 1) Paul’s near-death at the hands of Megaera; and, 2) Paul and Namaroff’s final duel in the castle. Between these two moments, Paul and Namaroff seek the affections of Carla, while Professor Meister attempts to unravel the mystery of Vandorf. Ultimately, Professor Meister’s theory proves correct, and the amnesiac Carla is revealed to be possessed by the spirit of Megaera after she is decapitated by Professor Meister himself.

This reveal is not an entirely shocking climax, for Carla is the only living female during the film’s last half. The other candidate – the mad woman Martha (played by Joyce Hemson) – is not only barely in the film, but is dead well before the film’s final unveiling. To make matters worse, when the audience is finally allowed to see the entirety of Megaera, the special effects and make-up are shown to be laughable. Roy Ashton’s gorgon mask, which was worn by Prudence Hyman, is only slightly ugly, while Megaera’s serpent-covered hair is obviously fake. In Kine Weekly, effects artist Syd Pearson said: “I’m going to use artificial snakes and they’re going to write, spit, and strike; they will be remotely controlled.” [2] Things could not be further from the truth, for the wig is clearly just a jumble of rubber snakes.

The special effects on The Gorgon were not solely to blame for the film’s mixed quality; the script, which had been originally penned by Gilling, had been drastically altered by John Elder (Tony Hind’s screenwriting pseudonym). Reportedly, Gilling was furious over this, and at one point wanted to have nothing to do with the film. Commercially speaking, The Gorgon represented a low point in Hammer’s history, and it simply could not appeal to the increasingly teenager-driven market.

The Gorgon did however get some good reviews, with Variety praising Fisher’s directing as “Restrained enough to avoid any unintentional yocks.”[3] The Gorgon is also an incredibly bleak film that ends with only one of its main characters (Professor Meister) alive. In Terence Fisher: Horror, Myth and Religion, author Paul Leggett champions the film for its smart use of mythology. Specifically, Leggett, who is also a Presbyterian pastor, claims that The Gorgon blends four mythological beings (The Gorgons, the furies, the sirens, vampires) into one sinister pagan goddess, who in turn is closer to the bloodthirsty and overtly sexualized goddesses of the ancient world.

While Leggett uses The Gorgon as a counter example to the feminist interpretation of the ancient goddesses, the fact remains that The Gorgon is a film more enjoyed by scholars and critics than by audiences. Gilling for one came away from the film angered by his treatment at the hands of Hinds-Elder. Luckily for him, The Gorgon represented Hinds’s last stewardship of Hammer. This allowed Gilling to exercise a little more freedom over his next work for the studio, and, in 1966, Gilling would see to completion his two greatest films.

Act II: The Reptile

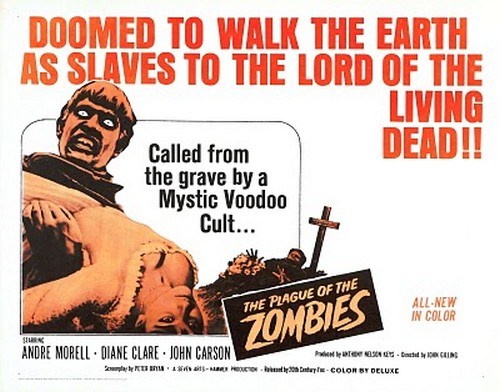

1966 was a big year for Hammer. Not only did Gilling’s “Cornish duo” hit the theaters as second features, but such Hammer classics as Fisher’s Dracula: Prince of Darkness and Don Chaffey’s One Million Years B.C. (which helped to make a star out of Raquel Welch) helped to resurrect the company after a series of questionable films. The first of Gilling’s “Cornish duo,” The Plague of the Zombies, has gone on to become a cult classic, while the other – The Reptile – currently holds some appeal amongst Hammer horror enthusiasts. While The Plague of the Zombies is the better of the two, The Reptile held a special place in Gilling’s heart, for he saw the gutting of Elder’s original screenplay as a bit of justice done in the name of his original treatment for The Gorgon. Indeed, The Gorgon and The Reptile bear much in common, with both films having serpent-friendly women as their supernatural antagonists. In The Reptile, Anna Franklyn (played by Jacqueline Pearce), the daughter of the scholar Dr. Franklyn (played by Noel Willman), suffers from a curse that turns her into a fanged reptilian monster. The Reptile, which is more or less lifts its plot from Bram Stoker’s The Lair of the White Worm (1911), presents a Cornish village turn apart by a foreign evil. This theme was also central to the earlier The Plague of the Zombies, except in that film the evil emanates from Haiti, not Borneo.

Considering that both films in the “Cornish duo” take place during the heyday of the British Empire, a post-colonial reading is certainly available. Both films depict foreign malignancies eating away at the fabric of rural English society, and both films showcase how prolonged exposure to foreign, non-European cultures can lead to the disintegration of the English family. The Reptile begins when Harry and Valerie Spalding (Ray Barrett and Jennifer Daniel) inherit the home of Harry’s brother (played by David Baron), who has only recently passed away under a cloud of mystery. The Spaldings find the local villagers reticent and afraid of the “Black Death” that is lurking in their village. Eventually, the local pub landlord, Tom Bailey (played by Hammer favorite Michael Ripper) befriends the couple and aids their quest to uncover the cause of Charles Spalding’s death.

The cause of this evil of course stems from the couple’s neighbor, Dr. Franklyn. While he was investigating a secretive tribe of snake people in Borneo, a curse was placed on Anna, forcing her to become a hideous snake creature every winter. Roy Ashton’s make-up for The Reptile creature is exceptional, which is made all the more interesting due to the fact that unlike Barbara Shelley in The Gorgon, Jacqueline Pearce played both the attractive Anna Franklyn and the gruesome cobra-woman. As per usual for a Hammer feature, the cinematography of The Reptile, which was done courtesy of Arthur Grant, is stellar. The set for The Reptile, however, is a little contrived. A sharp-eyed viewer can easily discern that Bernard Robinson merely revamped Castle Dracula in order to create the Cornish village. Furthermore, the village in The Reptile looks almost exactly the same as the village in The Plague of the Zombies, and if one were to watch both films back-to-back, then Gilling’s “Cornish duo” becomes a two-part piece about the strange goings-on in an isolated Cornish village.

As a stand-alone piece, The Reptile is a serviceable horror film with a modicum of appeal. Its exciting monster and its above-average scenery more than make up for its barely-there plot. Clearly, The Reptile suffers a little from hasty shots and Hammer’s many money and time constraints. Also, at the time, The Reptile was seen as too much in a year already full of Hammer productions. Most viewers and critics thought of The Reptile as being too similar to its direct antecedent in the “Cornish duo,” as well as inferior.

Frankly, The Reptile is indeed worse than The Plague of the Zombies, but The Reptile does contain some engaging ideas, as well as some beautiful shots. The shots of the sulfur-spring below the Well House (the abode of the Franklyns and their Malay servant [played by Marne Maitland]) offer a feast for the eyes, and the final familial battle between Dr. Franklyn and Anna is more action-packed and only a little less emotionally gripping than Don Alfredo Corledo’s killing of his son Leon Corledo in Fisher’s The Curse of the Werewolf (1961). Still, The Reptile is a pale cousin to The Plague of the Zombies, and time and history have shown that the first part of the “Cornish duo” belongs in the weird pantheon of influential fright films.

Act III: The Plague of the Zombies

Although it was only filmed in an amazing twenty-eight days (The Reptile took only four days more to complete), The Plague of the Zombies remains one of Hammer’s most inventive and original films, and it has gone on to earn a position as one of the best horror films of the 1960s. In particular, The Plague of the Zombies, which again features Roy Ashton’s fantastically ghoulish make-up, has a strong showing in the heavy metal community, with bands such as the Swedish death metal outfit Death Breath (which features former Entombed member Nicke Andersson on drums) featuring one of the film’s zombies on the cover of their debut album. Even more notably, Phil Anselmo, the former singer for Pantera and the current frontman for Down and Phil Anselmo and the Illegals, has one of the film’s zombies tattooed on his bicep.

The influence of The Plague of the Zombies extends beyond music into its own world of film. Even though it lacks Fisher, Cushing, and Lee – Hammer’s unholy trinity – The Plague of the Zombies managed to infect a later round of horror films, especially since it was one of the few films at the time that used the figure of the zombie as its supernatural center. It’s not crazy to say that Gilling’s film anticipates George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, and it is also not absurd to claim that the film improves upon Roger Corman’s technique of the “nightmare-sequence” in order to create its most famous scene (which, while part of Peter Bryan’s script, was greatly embellished by Gilling).

Some of the success of The Plague of the Zombies can be credited to Gilling’s improvisational directing style. Although the film’s dialogue is taken almost word-for-word Peter Bryan’s screenplay, there is a free-flowing quality to The Plague of the Zombies. Much like the recordings of punk rock and extreme metal bands, Gilling’s film manages to somehow make its cheap and rushed production (which was done entirely on the back lot at Bray) its greatest attraction. The film’s new spin on a previously hackneyed subject matter also gives The Plague of the Zombies an extra allure, along with (again) its pristine coloring and excellent cinematography.

The film opens with an exotic drum circle that soon shifts to an occult ceremony. The participants in this ceremony are both white and black, thus suggesting a ghastly type of miscegenation. Also, considering that this film was released in the same year that Time magazine popularized the term “Swinging London,” the evil in The Plague of the Zombies can be seen as an early commentary on the New Age practices and beliefs of the era’s counterculture. Either way, the film opens with sensational suggestions of voodoo curses and blood rituals.

From there, the audience is introduced to the crotchety Sir James Forbes (played by the well-respected André Morell) and his daughter Sylvia (Diane Clare). Forbes, who is looking forward to spending his holiday fishing, receives a letter from his friend and former pupil Dr. Peter Thompson (Brook Williams) in Cornwall. Dr. Thompson claims that an unknown malady is tearing apart his village, and that he alone is unable to either contain it or defeat it. Although he’d rather not go all the way out to Cornwall, Sylvia convinces her father to visit Dr. Thompson and his wife Alice (played by Jacqueline Pearce). While on the road to the plagued Cornish village, Sir James and Sylvia come across some red-coated fox hunters whom Sylvia purposely throws off-track in order to save the fox. Unfortunately, Sylvia’s misdirection puts the hunters in the very same village as the ongoing sickness, and their zest to find the fox causes them to interrupt a funeral. One of the riders causes the pallbearers to fumble the casket, thus uncovering the pained face of the corpse. This is Sylvia and Sir James’s first taste of this bizarre village, and the theme of class division is only further emphasized as the film progresses.

The strangeness of the village only deepens when Sylvia and Sir James are greeted by an anemic-looking Alice, who was shown in the film’s opening as being tortured by the voodoo-like ritual. Alice’s declining health and eventual death, along with the numerous deaths in the village, help to further increase Dr. Thompson’s desire to perform autopsies on the village’s recently dead. He is prevented from doing this by the superstitions of the villagers, as well by the iron rule of the menacing Squire Clive Hamilton (played by John Carson). In his first moment on screen, the camera focuses on Squire Hamilton’s strange ring – a ring that looks eerily similar to the one worn by the masked occultist during the opening credits.

And thus the film the reveals its antagonist. Unlike The Gorgon, The Plague of the Zombies does not rely on the trappings of a mystery (how could it, given its title?) and from the very moment when Dr. Thompson spits out Squire Hamilton’s name, the audience knows that the soon-to-come zombies have something to do with the village’s small-time dictator. Indeed, Squire Hamilton’s many years spent in Haiti introduced him not only to voodoo rituals, but black magic more generally. Now, in Cornwall, Squire Hamilton busies himself with turning the locals into the living dead. He eventually sets his sights on Sylvia, and after collecting a sample of her blood after an accident involving a wine glass, Squire Hamilton uses the dark arts to lure Sylvia to the abandoned tin mine that he uses for his blasphemous deeds. As in Bram Stoker’s most famous novel, The Plague of the Zombies forces its men of science to face the supernatural in order to rescue a female caught in the clutches of evil. Sir James and Dr. Thompson are successful in the end, and like most things in horror, the zombie plague is destroyed by an all-cleansing fire.

While its plot is not terribly unique, the visuals of The Plague of the Zombies are. From the psychedelic “nightmare-sequence” to the first on-screen appearance of a zombie, Gilling’s film is a Smörgåsbord of eye-catching images. In The Plague of the Zombies, Gilling, who was fifty-three at the time, seemed to have his eyes tuned towards the new generation, what with their acid rock aesthetics and their semi-mystical interests. It’s no wonder that some many metalheads find inspiration in Gilling’s film, for it, along with the other innovative European and American horror films of the mid-1960s, gave the burgeoning metal sound a visual analogue in the image of lurking zombies in the mist.

Act IV: Curtains

The “Cornish duo” represent Gilling’s artistic sunset. After The Reptile, Gilling would make only one more film for Hammer – the forgettable The Mummy’s Shroud (1967). By the early ‘70s, Gilling was living in semi-retirement in Spain. His final film – 1975’s La cruz del diablo (Cross of the Devil) – was directed and written by Gilling himself, and starred a Spanish cast. The film, which involves a British novelist traveling in Spain, is partially an allegory about Gilling himself, while at the same time a horror film of its time. La cruz del diablo is in the same vein as the other Satanic horror films of the mid-1970s, and its devil-worshipping bandits speaks volumes about the West’s backlash against the sputtering counterculture. La cruz del diablo is not Gilling’s finest film, and it lacks the idiosyncrasies of his “Cornish duo.”

At the very least, The Gorgon, The Plague of the Zombies, and The Reptile, should be lauded for their unusual subjects matters, especially considering that they were made under the banner of a company that had become famous due its re-imaginings of the old Universal monsters from the 1930s. While The Gorgon belongs more to Fisher, the “Cornish duo” are undeniably the property of Gilling. The Plague of the Zombies and The Reptile are the two of the best Hammer films from the 1960s, and considering that Hammer reached its pinnacle in that decade, Gilling deserves some credit for at least helping to improve an already beloved brand. Further evidence of Gilling’s inextricable role in the creation of Hammer’s halcyon era can also be found in the studio’s popular nickname – “The House of Horror.” This handle made its first appearance in the advertisements for the Rasputin, the Mad Monk/The Reptile double feature. Whether or not he was a better-than-average housekeeper or a small-time genius, Gilling is in the DNA of Hammer in much the same ways as Fisher, Cushing, and Lee. Without Gilling, Hammer would have slouched through the 1960s on the increasingly tired legs of Fisher. Without Gilling, the Hammer catalog would be missing some of its most exclusive titles.

[1]Quote is taken from page 194 in Denis Meikle’s A History of Horrors: The Rise and Fall of the House of Hammer. The Scarecrow Press: Lanham, MD and London, 2001.

[2] qtd. in Meikle, 179

[3] Quote taken from page 71 of Howard Maxford’s Hammer, House of Horror: Behind the Screams (Overlook Press: Woodstock, NY, 1996).

3 thoughts on “Hammer’s Forgotten Horrors: John Gilling’s Three Horror Classics from the 1960s”

Comments are closed.

All three are favorites of mine. Took me years to find “The Reptile”. I didn’t like “The Gorgon” as a kid, but now I appreciate its eerie atmosphere. And I absolutely love Andre Morell…he holds his own with Lee and Cushing.

“The Gorgon” is hard to swallow for youngsters – it’s just so slow and melodramatic in parts. But, in terms of atmosphere, it’s the best of the three. “Plague of the Zombies” is my personal favorite of the three. I feel bad for “The Reptile” – it’s not a bad Hammer flick, but it’s no so great that it’s either memorable or praiseworthy.

Are you aware of which snake stands out as the longest?