When Robert Bloch came to Hollywood in the early 1960s, he did so as an already accomplished and acclaimed author. In this regard, Bloch was nothing new. Plenty of writers, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner, had chosen a similar career path. But unlike Fitzgerald, who washed out in Hollywood as an alcoholic mess, and Faulkner, who was just as big of a drunk as Fitzgerald, but more successful in Tinseltown, Bloch primarily worked in his chosen genre (horror) and rarely ventured out of the B-movie ghetto.

By the late 1950s, the pulp magazines, which had provided Bloch with his primary publishing vehicle since the 1930s, were drying up. While still a successful writer of short stories (most of which were being published in slicker genre pieces like The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Ellery Queen), Bloch, urged on by his wife Marion’s ill health, took a job as a writer and sometime guest panelist for the Milwaukee-based quiz show It’s a Draw. Now at aged 41, Bloch felt like a failure. According to both his biography and The Bat is My Brother, an unofficial website dedicated to Bloch, Bloch summed up his achievements up to this point and diagnosed them as severely lacking:

Twenty-four years a professional writer, and what to show for it? A few published books, only two of which appeared in hardcovers a dozen years before. Lots of short stories, most of them sold for one cent a word. A few in men’s markets, some reprinted in anthologies; a bit of critical recognition, but this was sporadic enough and hardly a food substitute in case the money ran out….

Bloch’s bad luck all began to turn around in 1959. In that year alone, Bloch won a Hugo (SciFi’s version of a Bram Stoker or an Edgar Award) for his short story “That Hell-Bound Train,” plus Psycho, his most famous novel, was released. Psycho was based slightly on the real-life crimes of Ed Gein, a native of Plainfield, Wisconsin who became known to authorities in 1957 as a necrophile, murderer, and a self-taught decorator who used bones and human skin as materials. At the time of Gein’s arrest, Bloch was living in nearby Weyauwega, Wisconsin. Despite this close proximity to Gein’s infamous farmhouse, Bloch later claimed to have only been partially inspired by the events, telling interviewer Paula Guran that he was surprised to discover “how closely the imaginary character I’d created resembled the real Ed Gein both in overt act and apparent motivation.”

Besides Gein, other influences on Psycho might well have been Castle of Frankenstein publisher Calvin Beck or just simply the old adage that “a boy’s best friend is his mother.” Whatever the case, Psycho gained the attention of Alfred Hitchcock, and in 1960, Bloch’s novel was adapted for the screen. Hitchcock’s Psycho, with a screenplay by Joseph Stefano, has gone on to become one of the most influential, if not the most influential horror film of all time. Sadly, Bloch had very little to do with the film. In fact, at the time and even now, Bloch’s name either gets lower-tier billing or polite exclusion whenever the film is brought up in conversations or is advertised. As an example of this brush-off, Bloch’s proposed script for Psycho II was rejected and so too were various other screenplays that Bloch pitched around Hollywood.

These dismissals must have hurt, but they did not stop Bloch from moving to Hollywood in 1960. At first, Bloch found work in television, but due to a Writers Guild strike, Bloch spent a few months on the shelf as a writer not allowed to write. After the strike, Bloch managed to churn out great teleplays for such classic shows as Alfred Hitchcock Presents, I Spy, and Bus Stop. At the same time, Bloch was still penning short stories and novels, one of which was co-written with a young editor at Regency Books named Harlan Ellison.

In 1962, Bloch finally got the chance to write for a Hollywood film. His first screenplay was for Owen Crump’s little-known thriller The Couch. Bloch’s next screenplay seemed, at first, like the very project that was going to put his career in full motion forward. Directed by Roger Kay, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari proved to be a thoroughgoing debacle. First of all, despite the title, Kay’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari has almost nothing to do with Robert Wiene’s German Expressionist classic. Second of all, Kay’s abuse of Bloch was legendary, and Bloch’s autobiography, Once Around the Bloch, devotes pages upon pages to Kay’s attempts to rob Bloch of the writing credit he deserved. Ultimately, the 1962 version of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari proved to be a monumental flub.

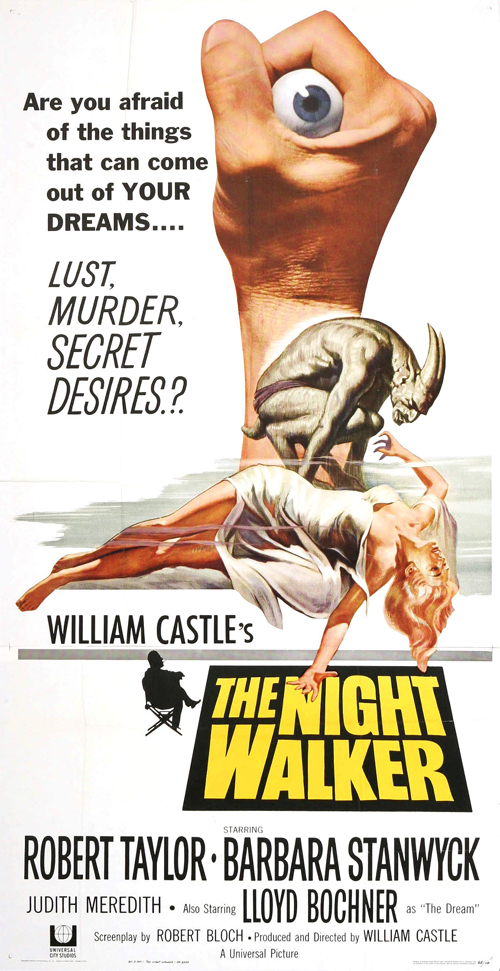

Undeterred, Bloch continued to try and sell his stories in Hollywood despite his horrible experience with Kay. In 1964 alone, Bloch wrote two screenplays for William Castle, the king of gimmicks and the man responsible for such schlock as House on Haunted Hill and 13 Ghosts. Unfortunately for Bloch, Castle was an anemic version of his former self by 1964. As if to signal his declining powers, Castle picked Bloch to write two screenplays for two aging female stars of yesteryear – Joan Crawford and Barbara Stanwyck.

The first film, Strait-Jacket, is the superior of the two. Starring Crawford, an actress who got one of her earliest starring roles in a silent Tod Browning-Lon Chaney horror collaboration called The Unknown, and Diane Baker as a murderous mother-daughter tandem, Strait-Jacket presents the story of the recently released axe murderer Lucy Harbin (Crawford) and her attempts to reconnect with the daughter (Baker) who saw the killings so many years before. As one of the earliest “psycho-biddy” movies about a deranged mother on a killing spree, Strait-Jacket didn’t fair too badly upon release (which was in no doubt helped by Castle’s trademark promoting, which included putting Crawford on tour and handing out cardboard axes to audience members), even though it was called “dreck” (Films in Review) and a murder-and-madness B movie (New York Herald Tribune) by the self-appointed tastemakers.

A more cynical eye could call Strait-Jacket a knock-off Psycho with a twist (Spoiler Alert: the killer is a mother-obsessed female, not a mother-obsessed male). Still, Strait-Jacket is arguably Bloch’s best American film, and besides being one of the earliest on-screen appearances of Lee Majors, everyone’s favorite second favorite Steve Austin, Strait-Jacket did a lot to help revitalize the career of Crawford. Although Variety correctly calls Castle’s directing “stiff and mechanical,” the film does have some dazzling murder scenes, plus the Freudian symbol of Lucy’s obnoxiously loud wrist bracelets is a fitting precursor to the calling cards of later cinematic axe murderers.

As for Bloch, Strait-Jacket (and screenplays in general) limited his capabilities, and for the most part the film’s dialogue is straightforward communication, if not a little hysterical at times. The one moment of typical Bloch ghoulishness comes when Lucy and Carol Harbin go shopping. Outside of the department store, Lucy sees a bunch of young girls playing and reciting a murderous nursing rhyme that has her as the main subject:

Lucy Harbin took an axe, gave her husband forty whacks, when she saw what she had done, she gave his girlfriend forty one. Take the key and lock her up, lock her up, lock her up, take the key and lock her up, my fair lady.

The second Castle-Bloch undertaking was The Night Walker, a confusing psychological thriller that stars Stanwyck in her last motion picture performance. Stanwyck, who is best known for playing film noir’s most vile temptress in Double Indemnity, plays Irene Trent, the wife of the blind millionaire Howard Trent (played by Hayden Rorke). Howard is made easily jealous, and the wealthy inventor is convinced that his wife is having an affair with Barry Moreland (played by Robert Taylor), the only person who ever bothers to come to the Trent mansion. While Irene remains faithful, she does have reoccurring dreams involving a handsome mystery man and lover. After an explosion in Howard’s upstairs laboratory suddenly leaves Irene a widow, the man from her dreams (played by Lloyd Bochner) begins paying her visits in the flesh. Although this sounds like the ideal, Irene’s world swiftly becomes a nightmare full of ghostly visitations (the ugly face of Howard pops up everywhere), suspicious dinner dates and elaborate weddings with her dream lover, and even more suggestions that Irene’s interior and exterior worlds are colliding together.

The second Castle-Bloch undertaking was The Night Walker, a confusing psychological thriller that stars Stanwyck in her last motion picture performance. Stanwyck, who is best known for playing film noir’s most vile temptress in Double Indemnity, plays Irene Trent, the wife of the blind millionaire Howard Trent (played by Hayden Rorke). Howard is made easily jealous, and the wealthy inventor is convinced that his wife is having an affair with Barry Moreland (played by Robert Taylor), the only person who ever bothers to come to the Trent mansion. While Irene remains faithful, she does have reoccurring dreams involving a handsome mystery man and lover. After an explosion in Howard’s upstairs laboratory suddenly leaves Irene a widow, the man from her dreams (played by Lloyd Bochner) begins paying her visits in the flesh. Although this sounds like the ideal, Irene’s world swiftly becomes a nightmare full of ghostly visitations (the ugly face of Howard pops up everywhere), suspicious dinner dates and elaborate weddings with her dream lover, and even more suggestions that Irene’s interior and exterior worlds are colliding together.

A consumable Jungian tale of shadows, The Night Walker is in actuality an intricate tale of extortion, murder, and betrayal. By the film’s climax, Irene is the only one left standing with any credibility as it becomes apparent that those around her are simply out to get her fabulous riches. If you need any reassurances that The Night Walker, which was filmed in a mere thirteen days, is far from Castle’s best film, then look no further from the fact that it still has not yet been released on DVD (but is free on YouTube). Adding insult to injury, the novelization of The Night Walker was done by another writer (Sidney Sheldon, an alias used by Michael Avallone), although Bloch’s name and his novel Psycho got top billing.

Bloch’s work in early-‘60s Hollywood is uneven, while his television scripts were typically tremendous. While Kay had done everything to bury Bloch, Castle was a much more convivial sort. Strait-Jacket is their masterstroke of B-grade murder, while The Night Walker is the very definition of “forgettable.” Luckily for Bloch, his best movie work lay ahead him. In the unlikely locale of rural Shepperton, Surrey, England, Bloch would find the right studio (Amicus Productions) and the right people for his macabre imagination. Bloch’s Amicus screenplays of the ‘60s and ‘70s are classic horror, and will be the subject of “Bloch in the Movies Part 2.”