Time is running out to save Dee and prevent Christina Braithwhite from completing her dark ritual. Tic, Leti, and Company, with the Book of Names in possession, must return to Ardham for a final confrontation with the evils of the Order of the Ancient Dawn, a confrontation in which all timespace hangs in the balance…

This didn’t work. Not just “Full Circle,” but Lovecraft Country itself. It’s a goddamn shame because at its best it was brilliant, reversing the Lovecraftian idea of the buried evils of the past to confront the real historical evil of racism and the odious slavery that was its nadir. But Lovecraft Country failed and I’m not going to pretend otherwise.

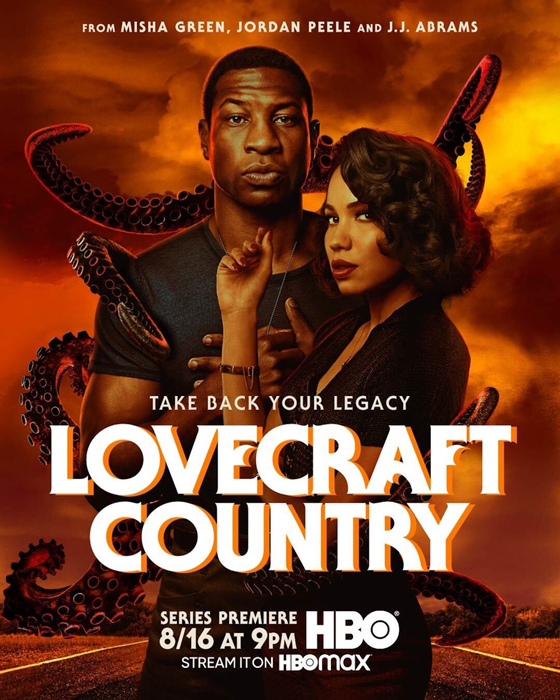

Oh, it had some great ingredients: the menace of the Braithwhite cult with its body horror machinations, Tic’s unhappy position as unwanted heir to the cult’s power, Korean fox spirits, travel through the multiverse, a secret language going back to Eden—not to mention powerful acting from talents like Michael K. Williams, Wunmi Mosaku, Courtney B. Vance, Jurnee Smollett, and Jonathan Majors. But I could take a cake from a five-star Parisian bakery, stuff it with filet mignon and Maine lobster, and slather it in truffle marinara sauce and I doubt you would enjoy eating it.

Much as it disappoints me to say it, Lovecraft Country suffers from American Horror Story Syndrome. Not as badly, mind you. I’d still rather eat that unappealing combination of great foods than slurp down a bowl of shit, but what both share is the mistaken belief that throwing the audience a bunch of tropes is the same as offering a coherent story with a logical plot and understandable character motivations. Lovecraft Country left me with many unanswered questions: why did Montrose slit Yahima’s throat? Where did the “shoggoths” come from? How exactly did Leti become invulnerable? How did Dee get fitted with a robotic arm? And why are white people now unable to use magic? What makes Lovecraftian horror special is that, as Robert Bloch pointed out, it’s logical. There may be fantastic elements, but at the end of the day, there’s a nightmarish rationality to Lovecraft that complements the horror of the unknown. As Lovecraft Country runs on, it loses horror and logic in equal measure.

There will doubtless be those who argue that Lovecraft Country’s failings are second to the conversations it starts and the representation it showcases. I will not countenance the racism inherent in such an argument. To judge work by creators of color on their ethnicity rather than the quality of their art is a monstrous infantilization and a tacit admission of the belief that black artists can’t do better horror than Lovecraft Country. If you are having Important Conversations About Race because of Lovecraft Country, then good for you. As a consumer of horror and dark fantasy, I regret to say I found it a disappointing waste of potential.

Despite that, I want Lovecraft Country to be successful. In fact, I want it to be wildly successful, making enough money that studio execs sit up and take notice, because despite the fact that it doesn’t work, it’s emblematic of a growing black horror renaissance, and that’s something we should all be happy to see.