“I could tell that I was at the gateway of a region half-bewitched through the piling-up of unbroken time-accumulations; a region where old, strange things have had a chance to grow and linger because they have never been stirred up.”

It is no secret that the works of Howard Phillips Lovecraft are exceedingly hard to capture on film. There has been no lack of creators making the attempt, but in almost every case, the original written word is superior to the filmed version. This is especially true when the adapters make the decision to bring the stories to the modern day. There’s something about modern times that just doesn’t gibe with Lovecraft’s period pieces set in gloomy, early 20th century New England, full of dark, mystery-haunted woods and decrepit backwoods towns.

The most recent version of The Colour Out of Space with Nicolas Cage was a happy exception to the rule. But even so, I’d still love to see a version of that classic tale set in its original milieu. A lot of the modernized HPL films lack the feeling of cosmic dread, of immemorial ancientness that is part and parcel of the HPL experience, substituting gore and sex to fill in the blanks which the creators seem unable to film.

“The Whisperer In Darkness” is a lesser-known Lovecraft novella that would seem to be even harder than most to adequately film. A tale of malevolent aliens infesting the lonely Vermont hills, it unfolds in an awkward way that relies on written letters and correspondence. If you would ask me to make a list of Lovecraft works that would be hardest to film, this story would be near the top.

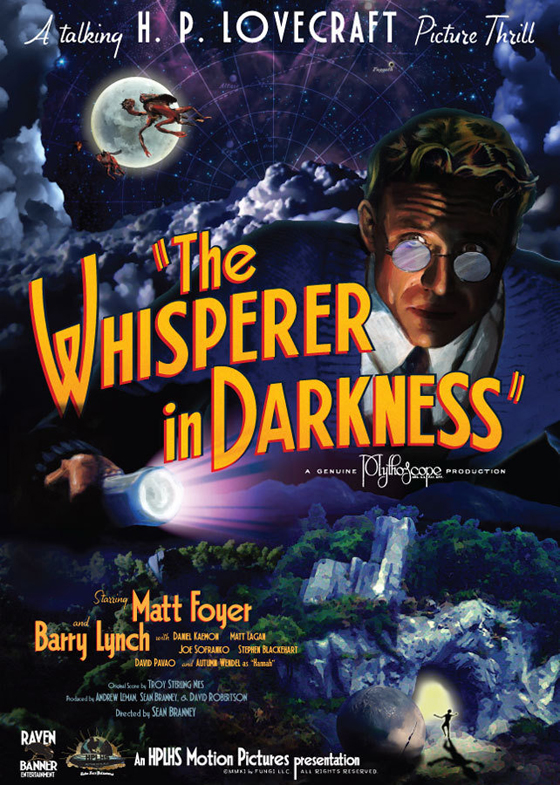

And yet the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society has found a way to do it and do it well. In retrospect, this shouldn’t be a big surprise. After all, these were the same folks responsible for doing the superb 2005 adaptation of The Call of Cthulhu. Instead of trying to modernize the story, the HPLHS completely embraced the period aspects of it. They filmed it as if it were a movie done at the same time Lovecraft wrote it … a silent black and white film, Lovecraft as filmed by a Fritz Lang or F.W. Murnau. The result has been judged as a spectacular success by those who have the imagination and mental ability to accept a 1920s version of the story.

This time the HPLHS applied their considerable talent to doing a similar adaptation of The Whisperer In Darkness. Here, they decided to make the film as if it were the 1940s … the time of Universal horror classics and Val Lewton’s mood pieces. Unlike the silent Call of Cthulhu, this movie uses the full range of sound and dialogue. It’s still shot in glorious black and white. For the most part, it also uses the kind of special effects prevalent in the 40s … although a couple of exceptions were made.

Other necessary changes were made in order to give the movie a cinematic flow. The time element would need to be compressed, as the print story unfolds over a long stretch of months. Mood, of course, would need to be paramount, but an injection of a couple of action sequences would bring a little adrenaline into the tale. The actual “sting” that ends Lovecraft’s story pops up in the middle of everything here (and a very creepy scene, it is, too). A controversial decision would be the choice to show the insectoid Mi-Go aliens in full glory … something Lovecraft’s story only hinted vaguely at.

But in most respects, the major aspects of “The Whisperer In Darkness” remain. It is certainly more faithful to the source material than other Lovecraft films like The Lurking Fear, Dagon and The Dunwich Horror. Would the notoriously crusty Lovecraft approve of the final product? We can only guess …

So, let’s take a closer look at the HPLHS film version of The Whisperer In Darkness …

The central character of our story is Professor Albert N. Wilmarth, an expert in folklore and legends working at Miskatonic University, the New England school of higher education that always seems to be involved in dark cosmic magic. Although Wilmarth deals in the fantastic and the supernatural, he is a strict rationalist and has no actual belief in the subjects he studies. But his most recent case will shatter that rationalism and take Wilmarth into realms of interplanetary horror. Wilmarth is brilliantly played by Matt Foyer, who gives the Professor a feeling of real humanity, mostly missing in Lovecraft’s story.

Massive flooding has struck the secluded Vermont mountains. Among the flood’s debris are found the strange, repulsive remains of creatures that resemble huge crustaceans. These creatures have long been spoken about in old Vermont lore as “them Old Ones”, who lurk in the caves and deepest valleys. Tales of these beings go far back into Indian days and even seem linked to legends from other parts of the world.

Wilmarth of course is an expert on these tales but dismisses the recent reports as superstitious claptrap. His associates at Miskatonic, including Dean Hayes, are not so dismissive. It is suggested that Wilmarth engage in a public debate with none other than the famous Charles Fort (Andrew Leman), who is a collector of facts that science cannot explain. Fort is never mentioned in the original Lovecraft story, but his inclusion here is a genius stroke that links the story with a real personage of the same time. One can only wonder what a real-life conversation between Fort and Lovecraft would have been like.

Wilmarth agrees and the two have a debate in front of a crowd mostly composed of Fort sympathizers. For the most part, Wilmarth comports himself well but falters when Fort confronts him with many known facts science can’t explain. When Wilmarth poo-poos the idea of mysterious creatures in Vermont, Fort challenges him to actually go to the area and see for himself. Wilmarth sheepishly agrees.

Later, when Fort meets Wilmarth and other faculty members privately in the Dean’s office, a young man named George Akeley appears asking to speak to them both. George and his father Henry live in an estate in the most remote part of the Vermont woods. They claim that the Old Ones have been harassing them at night while suspicious human characters are lurking around the estate by day. Shots have been fired and some of Henry’s guard dogs have been killed. George also brought photos of strange inhuman prints in the mud around the house as well.

Related Content:

Interview with Filmmaker Stuart Gordon: Re-Animating a Literary Icon

H.P. Lovecraft’s Witch House Movie Review

Wilmarth is intrigued and begins correspondence with the senior Mr. Akeley, who he finds to be a remarkably intelligent man. When Henry sends Wilmarth a phonograph recording of what sounds like some kind of ceremony, where human voices mix with strange, buzzing insect-like speech. Wilmarth now feels he must visit Akeley. He makes plans to visit and stay at the old man’s estate.

The journey to Akeley’s home is fraught with misadventure from the start. George Akeley never meets Wilmarth at the train station as agreed … he has suddenly “gone to California”. Instead, Wilmarth is greeted by a rather greasy and obsequious character called Mr. Noyes, who claims to be a longtime associate of Henry Akeley. It is Noyes who will convey Albert to the Akeley estate by way of car. The two set out on the journey through the dark and foreboding hills of Vermont.

I’ve always heard the wild spaces of Vermont described as beautiful, but in this movie, they are made to seem as ominous as any English moor. This is one instance where black and white photography helps immeasurably. There’s no way the forests would look so gloomy in their natural green glory.

As rain falls from the sky, Noyes’ car suddenly breaks down as they are within a couple of miles of the Akeley place. A furtive-looking farmer named Walter Brown appears and says the road is out … Wilmarth will have to trudge through the countryside to reach the estate. The professor is suspicious of both Noyes and Brown but takes off across unknown territory as rain patters steadily down.

Eventually Wilmarth reaches a lonely farmhouse … where the owner tells him to halt or be shot. This is Will Masterson, who is Akeley’s next-door neighbor and it is obvious this man is consumed by an agonizing fear. His farmhouse has also been harassed by the Old Ones and he shows Wilmarth fresh prints in the mud that have been made by no human being. Hovering in the background is Masterson’s young daughter, Hannah. Neither of these characters appear in the original Lovecraft story, but both will be very important in the film version.

Wilmarth convinces Masterson of his good intentions, and he is given instructions to reach the Akeley estate … even though he is also warned to stay away. The man of science is starting to feel his convictions crumbling in the face of overwhelming strangeness.

At last, Albert reaches the Akeley place … where the slippery Noyes has already preceded him. Noyes tells Wilmarth that Henry is ill and confined to his easy chair. He is apparently dealing with some kind of “respiratory problem”. Despite the illness, he is eager to speak to his long-distance friend and tell him some astounding news. After Wilmarth has a meal and is shown his room, he meets the old man he has been corresponding with the last few months.

It is an uneasy meeting. Henry is covered with thick clothes, including heavy blankets. The room is deliberately kept dark, as strong light seems to hurt his eyes. When Akeley speaks, it is in a weird, rattling cadence that is really creepy to hear. Yet he is cordial and glad to see Wilmarth. What he has to tell him is a complete reversal of everything he has written about before.

Akeley says he has made contact with the alien Old Ones and has learned that their intentions are not as menacing as he once thought. In fact, they are ready to usher the world into a new age of scientific discovery. Wilmarth himself will become a vital part of this age and may even venture mentally to Yuggoth, the home world of the Mi-Go, which corresponds to the planet Pluto.

Wilmarth is in disbelief. What Akeley is telling him is a direct contradiction to not only what’s been expressed strongly by him before, but it also goes against what Albert learned at the Masterson farm. He is very uncomfortable in the presence of Akeley yet is compelled to stay and learn further what’s actually going on.

The worst revelations are to come. Akeley reveals a hidden chamber full of strange equipment. There are many metal cylinders the size of a hatbox that can be hooked up to some kind of transmitter. Wilmarth is told that these cylinders each contain the brain of a human being … the mental essence of each person’s brain can be sent anywhere in the universe, including Yuggoth. One of the empty cylinders is meant for Wilmarth. Once he is free of his body, he can join Akeley on a great celestial journey of discovery.

Wilmarth is now absolutely horrified, but when he hooks up one of the cylinders to a transmitter, a disembodied face and voice appear. This is B-67, a human scientist whose brain is in the cylinder. He tells Wilmarth of the great joys yet to come when his mind travels unfettered through the universe. Nothing will be forced on him, but it is a great opportunity for any scientist.

It sounds too good to be true and it is. Unable to sleep, Wilmarth hears strange voices in the dead of the night and he creeps downstairs to get a better idea of what’s being said. Akeley is speaking and his voice is even more distorted than usual. Noyes is also there, and he speaks of beings like the dreaded Shub-Niggurath and of the “coming conjunction”. It’s the final voice that finally breaks Wilmarth’s courage … an electronic rasping of something that was never a human being. One of the half-crustacean/half-fungal Mi-Go is in the house!

The once skeptical scientist has stumbled onto a hellish extraterrestrial conspiracy to bring the repulsive Mi-Go to Earth, along with their god, Shub-Niggurath. His only duty now is to escape and warn the world before his brain is removed from his skull and put in one of the metal cylinders. The Mi-Go have many human collaborators and servants helping them in their unholy work. Wilmarth’s only real ally will be the spunky young girl, Hannah Masterson.

The last 20 minutes or so are a radical departure from the original story, involving Albert and Hannah’s madcap escape attempt. A vintage prop plane plays a large part in the escape, and we get to see plenty of the weird Mi-Go creatures. I think perhaps we see too much of them. And although most of the movie is done with old school practical effects, the Mi-Go … looking somewhat like flying crayfish … are obviously computer-generated. I think Lovecraft himself would not be pleased with the emphasis on the alien monsters.

I won’t reveal the actual ending of The Whisperer In Darkness but it’s pretty odd and much different than what old H.P. wrote. Because of this, it will be a surprise even to those familiar with the source material.

Despite minor misgivings, the movie is admirable in how it sticks to its vintage 1940s look. Even the faces of the actors seem to come from that elder time, 80 years or more in the past. Despite the authentic look, we don’t get the sugary ending that many 40s horror films had, with the romantic couple heading off into the sunset. The servants of the Old Ones are not so easily vanquished, and the movie is true to Lovecraft in this regard.

I also want to mention again the outstanding performances. Matt Foyer shines as Albert Wilmarth, making him a very human character. There’s a great scene late in the movie where he reveals the tragedies of his own past to Hannah Masterson, which adds depth to the rather cookie-cutter personality of H.P.’s original concept. I also have to hand it to young Autumn Wendel as Hannah. This could have been a cloying character, but she makes the most of it. Barry Lynch excels as “Henry Akeley” … you will definitely get chills listening to the strange speech of the old scholar … or what seems to be the old scholar.

All in all, The Whisperer In Darkness proves that Lovecraft on film works best when it varies the least from its original source. It has moodiness in abundance, a good look and the aura of the vast unknown. All of which were essential parts of the Lovecraft experience.