Imagine if you will the Massachusetts wilderness. Although today pockmarked by small towns and industrial cities, Massachusetts was once a vast forest. In the 1630s, the Puritans, those somber-faced people in felt hats and white coifs, mostly kept to the coast, for outside of the plantation walls was the forest—a vast, lightless land of trees, rocks, and mountains. Painted Native Americans carrying instruments of war also roamed those woods. But worse than them, indeed worse than anything imaginable, made that wilderness its kingdom.

Satan. The Devil. Old Scratch. The Puritans knew the chief architect of evil by many names. For them, Satan was everywhere, and everywhere his minions, those men and women they called “witches,” needed to be snuffed out. Most of the time, the Puritans prayed the monster away. Theirs was a society completely enveloped by faith, therefore faith was the first panacea against evil. When that didn’t work the land turned sour and the children turned sleepless, the Puritans called upon religious judges in order to hunt down the cause of the affliction. Thus the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 and 1693 happened, along with other, lesser known witch trials in colonial New England.

People today tend to blame the Puritans for this hysteria. After all, only religious cuckoos would hang women and stone men based on flimsy evidence purporting to show the machinations of the devil’s favorite worshippers here on earth. Keep in mind though, when the Puritans came to the Massachusetts coast in order to build a “city upon a hill,” Europe was centuries into its own witchcraft craze. Starting in the 14th century, the witchcraft trials in pre-modern Europe really picked up speed between the 15th and 17th centuries. In that time, Catholic and Protestant judges managed to condemn somewhere between 30,000 and 60,000 witches to death (modern wiccans, neo-pagans, and the like tend to inflate the figures in order to turn this period into their own Holocaust). Most of the victims were women, but plenty of men suffered the wrath of righteous justice as well. So, the truth is that the Puritans didn’t invent this fear; they just brought it to the New World. The fear of witchcraft didn’t stop with them either. In 1928, Nelson Rehmeyer, a suspected “powwow” doctor in Pennsylvania, was murdered by local men who were convinced that he had put a hex on their farms.

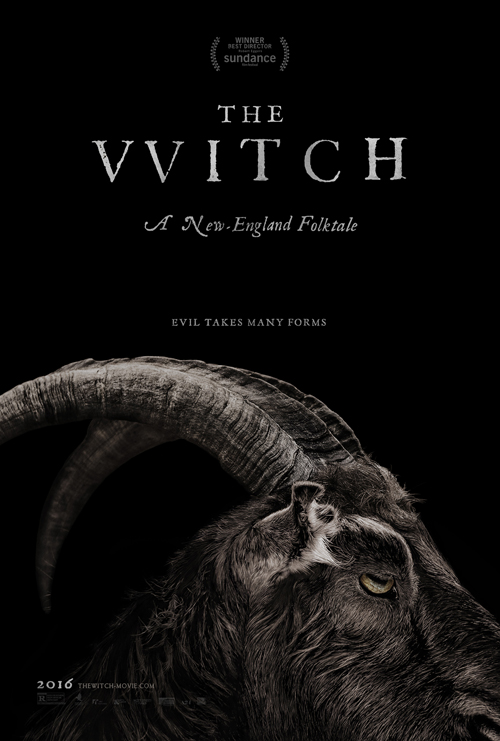

Puritans still reign in American culture as the preeminent demonologists; however, and writer/director Robert Eggers’ The Witch only serves to solidify that position. Subtitled “A New England Folktale,” The Witch expertly recreates the cultural gloom of 17th century Massachusetts. This is a place where the sun rarely shined and the harvests rarely made enough to last all winter.

Centered around a deeply religious family headed by the proud patriarch William (played by Ralph Ineson), The Witch tells a classic Puritan horror story about people in the godless wilderness. After being banished from a walled plantation (presumably Salem or Plymouth) for preaching the Gospel without the consent of the colonial authorities, William, his wife Katherine (played Kate Dickie), and their children Thomasin (played by Anya Taylor-Joy), Caleb (played by Harvey Scrimshaw), Mercy (played by Ellie Grainger), and Jonas (played by Lucas Dawson) head out into the foreboding wilderness in order to remake their pious lives. Within no time, fissures in their familial fabric start to show, as Katherine speaks of her desire to return to England, while Thomasin grapples with puberty.

The real catalyst for conflict comes when the infant Samuel is snatched away while under Thomasin’s supervision. The viewers know his horrible fate (I won’t reveal it, but suffice it to say that the sequence is the best in the film, with startling and disturbing images), but the family does not. The mystery tears them apart, so when Caleb and Thomasin get lost in the woods after trying to find food for the starving family, things fall apart even more when Thomasin finds Caleb naked and bewitched.

Like the historical records show, the afflictions of Samuel and Caleb, along with odd occurrences at the farm, such as goat’s milk turning to blood and the existence of a black and devilishly horned goat on the farm named Black Phillip, lead to suspicions of witchcraft. Mercy and Jonas blame their older sister. Katherine, who doesn’t seem to like Thomasin very much, readily accepts. William does not. Later on, he begins to suspect Mercy and Jonas after Thomasin tells him that the young pair regularly talk to Black Phillip. Eventually, all three children are boarded up inside of a small barn along with Black Phillip. Unbeknownst to Katherine, William, and the others, this will be their last night alive.

Frankly, The Witch is one of the best American horror movies of the last ten years or so. Along with other indie giants like It Follows, The House of the Devil, You’re Next, and We Are Still Here, The Witch forgoes stock jump scares in favor of mood and quiet terror. It’s a slow burn, but at no point does the audience feel completely secure. After all, the woods are always right there, hiding the unspeakable. Robert Eggers, the screenwriter and first-time director who has already been tapped to remake Nosferatu, should be commended for making such a thoroughly believable period piece. Indeed, not only does the language feel accurate, but the devilry described in the film is taken straight from the court documents of the time. The only anachronism in the entire film is Mark Korven’s music, which is reminiscent of the loud-to-loudest technique used by Dario Argento in Suspiria (which is another witch film, I might add).

On a narrative level, Eggers succeeds in making the audience question who is the real witch after all. Such mystery essentially disappears in the film’s final, campy moments, but post-film discussions between friends are sure to offer up multiple explanations. Overall, The Witch is a visual treat that is both style and substance. Most surprisingly, for a film dealing with the religious ramifications of Puritan thought, William, his family, and the Puritans in general do not come off looking like intolerant fools in The Witch. This may disturb some, but those are people who have no clue how terrifying America must have been to the inhabitants of early New England. The Witch does their paranoia justice.