Try to resist the impulse though we might, we define our eras by their crimes. You think of sooty, oppressive, desperately poor Victorian London and you think of Jack the Ripper. Get as dewy-eyed as you want about Woodstock and the Summer of Love, but a dark corner of the ‘60s will always belong to Charles Manson and the Family. And while he doesn’t command quite the same recognition, Ricky Kasso, the Acid King, became an icon of the 1980s.

Even in a decade filled with Satanic ritual sacrifice, the 1984 murder of Gary Lauwers stands out—probably because unlike every other alleged Satanic crime, it actually happened. Kasso, a homeless seventeen-year-old obsessed with the occult, survived on the streets of Northport, New York by selling LSD, and killed Lauwers, a former friend, under the influence of his product. But when Kasso commanded Lauwers to say he loved Satan while carving his eyes out with a knife, his legend was sealed.

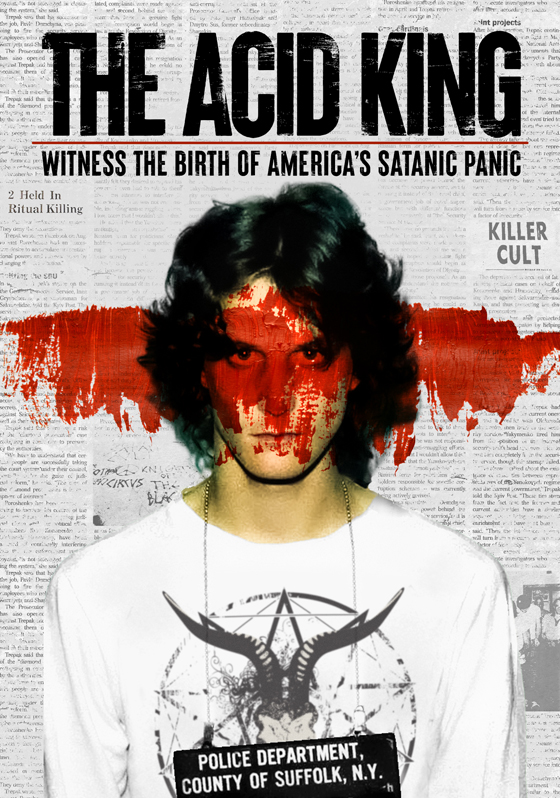

It’s a legend that Jesse P. Pollack and Dan Jones studiously avoid in their new documentary, The Acid King. Told largely through interviews with friends, classmates, and others who knew Kasso on a personal level, as well as a few directors and musicians who created work inspired by the case, The Acid King forgoes sensationalism in favor of a far more tragic reality. Rather than a teen Satanist rebel, Pollack and Jones paint a picture of a lost soul: homeless, angry, rejected, and lost in drug addiction. Kasso’s Northport isn’t a secret hub of devil-worship, but a town full of aimless, alienated kids who found solace in drugs and the ‘80s metal ethos of rebellion.

It’s a wise narrative choice that makes The Acid King a far more engaging film. By painting such a vivid portrait of the world that Kasso inhabited, The Acid King deftly shows that if he was a monster, he wasn’t a self-created one. The film discusses the cultural fallout of Lauwers’s murder only as an epilogue, instead posing a tougher and more haunting question: if the moral guardians of the time cared more about poverty, abuse, and mental illness than Ozzy Osbourne’s lyrics, would there have been a Ricky Kasso case? In an era of school shooter drills, it’s a question that remains all too relevant.

The Acid King dissects its subject with such skill, restraint, and sensitivity that it’s hard to find much to criticize. Certain segments replaying taped police and witness testimony could have benefitted from subtitles, but that’s a minor complaint. Pollack and Jones have created a powerful, nuanced, and at times difficult film. Here’s hoping it gets the attention it deserves—and needs.