Prolific filmmaker and horror legend Wes Craven passed away from brain cancer on August 30th, 2015—what was yesterday as I type these words. I had no idea he was sick so his death comes as quite a shock. The malevolent “C-Word” snatches another one from our midst and leaves a hole in horror cinema that’s deep and wide. More importantly, though, is that by all accounts we lost one of the good guys in this business.

Unlike some of the other people who will inevitably write about his passing and eulogize him over the coming days, I never got to meet Wes Craven. But I feel that in some ways I knew him quite well. So here’s the story of Wes and me, the short version.

I was eight years old in 1984. My mother taught theater at a liberal arts college and my dad was a mailman, someone who worked hard all day then came home and watched movies. Despite the fact that we were broke, my parents’ proclivities assured that one of our 10 or so television channels was HBO, and trips to the movie theater were frequent. The two of them—my mom and dad—in their unique ways, bestowed upon me and my older brother a love for cinema, performance, storytelling and art. But they didn’t get along and that year they began what was a long, painful process that inevitably ended in divorce. Soon my mom moved out and my brother followed her.

It could have been a coincidence, or it could have been because the turmoil at home made me gravitate toward dark things, but 1984 was also the year that I discovered slasher flicks. I had been a monster-kid and I loved movies and TV like Jaws, Poltergeist, and Scooby Doo, but at eight years old it had been difficult to get my hands on the hard stuff. Then one of the first things my mom did when she got her own place was buy a VCR. It changed everything.

I stayed with my mom a few nights per week and the ritual was always the same. She’d pick me up at my dad’s place and we’d drive across town to one of two—the first two—movie rental places in my hometown of Beloit, Wisconsin. She’d peruse the “boring old movies” while I’d scrutinize every single display box for what quickly became the easily identifiable artwork indicating a horror movie, an exploitation flick, or something weird, gross, and terrifying lurking inside. I loved it. I saw everything.

The first slasher flicks I watched were Friday the 13th and its first two sequels followed by Halloween and its first two sequels. I was hooked on this gory, violent style of horror—a style I knew was meant to be consumed by people much older than I was. I’d caught up with the genre over the first year of my VCR access and then in early-1985 I rented A Nightmare on Elm Street. It was immediately apparent that this slasher flick wasn’t like the others. Somehow, some way, it transcended the formula and took horror to a new place, both literally and figuratively and it blew my not-quite-nine-year-old mind.

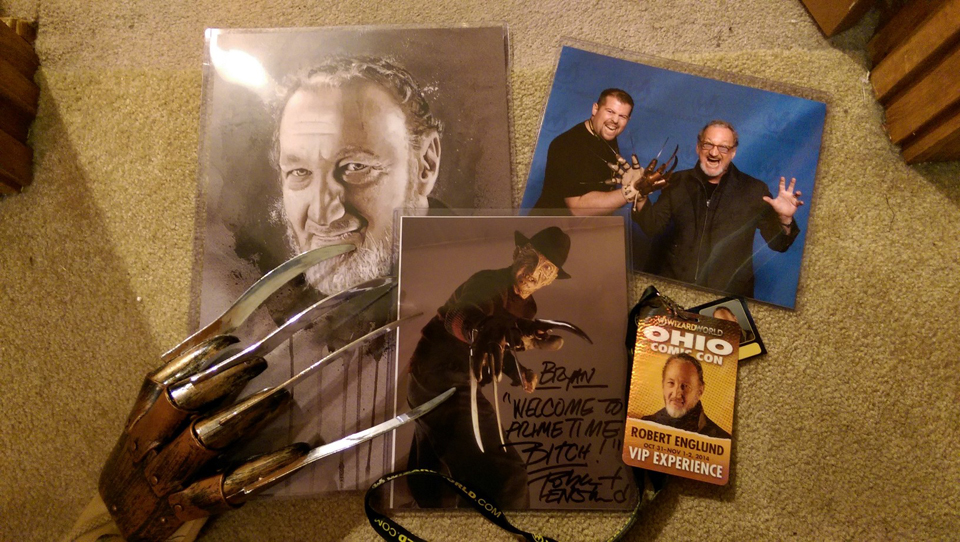

Wes Craven’s boogieman leapt over his peers in a multitude of ways. Freddy Krueger—his burnt flesh, the fedora, the dirty Christmas sweater, and the glove…THE GLOVE, redefined the term “horror antagonist.” And this maniac wasn’t a mere mute killing machine. He was a chatter box and a malicious, lecherous one at that. It was high-concept terror to which we were all susceptible; everyone sleeps and we’ve all had nightmares. Craven’s masterpiece wasn’t just scary and immediately iconic, but through the lens of retrospection it’s also arguably one of the top ten horror films of all time. To the eight-year-old me, watching A Nightmare on Elm Street was a profoundly wicked time akin to experiencing the entire month of October if it had been pumped up with steroids and compressed into a svelte 90 minutes.

Most importantly, Nightmare was one of the first movies that compelled me to seek out other movies by the same filmmaker. Craven’s sleazy and disturbing earlier works, The Last House on the Left and The Hills have Eyes, soon became part of my heavy VHS rotation and they cracked open the door to the previous decade’s macabre cinematic exploits. To my absolute delight I learned that Swamp Thing—a movie my brother and I had watched on HBO a gazillion times together in our basement—was also a gift from Mr. Craven. And, of course, his subsequent movies—Deadly Friend, The Serpent and the Rainbow, Shocker, and The People Under the Stairs—were movies that I saw on the big screen almost entirely because of the name “Wes Craven.”

Craven’s influence over me didn’t stop at the video store or the movie theater. I dressed as Freddy the last two times I went out trick-or-treating, probably in 1987 and ’88. When I ran for Sixth-Grade Class President at Gaston Elementary School, I cut up what had been the current issue of Fangoria—it featured A Nightmare on Elm Street 4–and I used the guts to make posters essentially blackmailing kids into voting for me or facing the wrath of the king of nightmares. I lost to a kid named Peter, but my ad campaign lives on in infamy. And being that I’m the quintessential horror nerd, I still own the aforementioned gutted issue of Fango. I may have even yelled, “Up yours with a twirling lawnmower,” to those kids unfortunate enough to have been caught in my political crosshairs back then, but I can’t say for sure.

I was an adult by the time New Nightmare came out and later Scream. I saw those in the theater, too, and had been disappointed, largely because as an angry, somewhat crazy young adult I had been chasing Freddy’s ghost and failing to catch it. In the context of the mid-90s, which was an awful time for horror movies, I rejected the meta-fictional experience of New Nightmare and I was outraged at the great Wes Craven for winking at me instead of trying to scare me in earnest with the Scream movies. But unlike other pop cultural phenomena that wowed me early and later broke my heart (hello, Metallica), those perceived missteps didn’t diminish my love for Craven’s earlier work.

It would’ve been foolish to hold a grudge against Wes Craven for failing to re-ignite the experience A Nightmare on Elm Street gave me. With Scream, he tapped into the monster-kids of the next generation—the ones who hadn’t seen Friday the 13th and Halloween—and he laid out the tropes and then made those kids go find those movies and watch them just like he did to me with Nightmare. Last House led me to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre which led me to Deranged and on and on. I imagine that for many of my younger peers who cover the horror genre, Scream led them to the movies with the garish, nasty artwork on their cases that I had so coveted a decade earlier.

My copies of A Nightmare on Elm Street, The Hills Have Eyes, Swamp Thing, The Serpent and the Rainbow, and The Last House on the Left are among the things I carry. I carry them with me from place to place, from apartment to apartment, and from house to house because they are among the items I own that make a place my home. And I carry them in my heart and in my imagination so that some semblance of that excited monster-kid lives and breathes—the one who was sad that his parents didn’t love each other and afraid of what life was going to be like without his mom and brother at home…the one who found solace at Camp Crystal Lake, in Haddonfield, and most certainly on Elm Street. Things worked out and that kid is alive and well no matter how old I am otherwise.

Thank you, Wes Craven. You didn’t know me, but I certainly knew you.

3 thoughts on “Wes Craven and Me: A Eulogy from Generation-X”

Comments are closed.

That Wes Craven was able to rip a film from the headlines (with echoes of the mass hysteria surrounding the infamous McMartin case) and create a solid gold horror premise that is surreal and ambitious even within it s limited budget, was a masterstroke.