You watch any pre-George Romero horror movie and you know the monster is going to go after the hot blond. There’s a certain Victorian sensibility to this, the contrast of the innocent maiden with the creature of darkness, though of course the trope was already old when St. George liberated a virgin princess from a predatory dragon. Sometimes the attraction makes a kind of logical sense; King Kong and Fay Wray are both higher primates, right? But what exactly does the Gill Man want with Julie Adams in The Creature from the Black Lagoon? Surely a Devonian monster isn’t lusting after a ‘50s B-movie starlet, is it? Maybe. In The Shape of Water, Guillermo del Toro asks, with characteristic brilliance, how exactly we define “monster.”

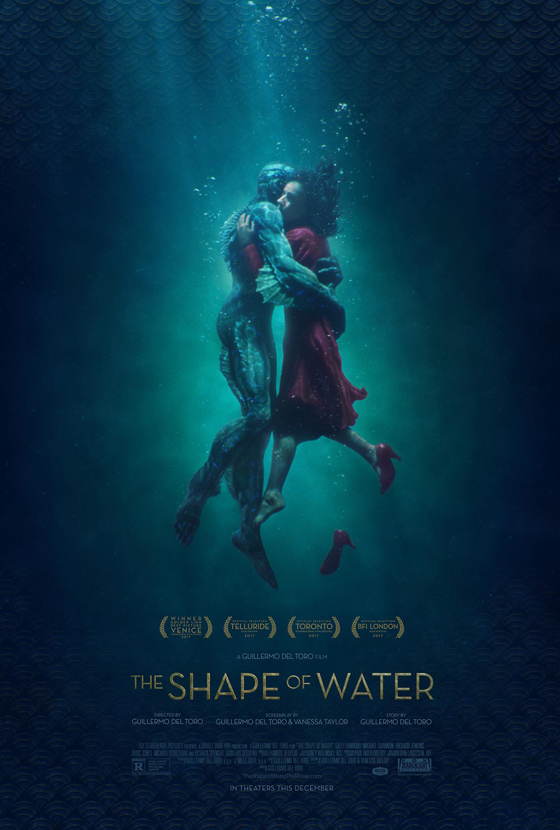

Set in the early 1960s, Shape takes as its protagonist Elisa Esposito (Sally Hawkins), a mute woman who works as a janitor at a military facility. Isolated by her inability to speak, Elisa lives a lonely existence, with only her talkative coworker Zelda (Octavia Spencer) and artist neighbor Giles (Richard Jenkins) as friends. Until one day, when ruthless Colonel Richard Strickland (Michael Shannon) brings a strange aquatic creature (Doug Jones, in all his contorted grace) to the facility for storage, unintentionally sparking an unforeseen romance for Elisa.

The performances in Shape are solid. The fact that Hawkins and Jones are able to generate such chemistry is a testament to the acting chops of both, and Spencer’s comic talents are well on-display as Zelda. Shannon’s role as the brutal Strickland retreads some of the same territory he tackled as fanatical Prohibition agent Nelson Van Alden in Boardwalk Empire, but hey, that’s what character actors are made for and Shannon once again turns out a satisfyingly detestable villain. Fellow Boardwalk Empire alum Michael Stuhlbarg capably portrays Robert Hoffstetler, a conflicted scientist with a dangerous secret.

Shape is probably del Toro’s most thematically complex work, rich with subtext and deconstructions. Hawkins’s atypical beauty is certainly a contrast to pinup girl Julie Adams, but in a film that questions appearances and traditional roles, she’s a perfect fit for the Amphibian Man’s bride. If the romance between an aquatic monster and a human being strikes us as monstrous, we’re invited to consider the plight of Giles, whose homosexuality would have been considered a diseased aberration in the era the film portrays. Just as del Toro contrasted fantastic monsters with human evil in Pan’s Labyrinth and The Devil’s Backbone, The Shape of Water shows us the monstrousness of the amoral Cold War and institutionalized prejudice of the ‘60s.

For all its complexity and beautiful cinematography, Shape has its faults. The ending has a deus ex machina quality that begs some logical questions. Midway through the film, Elisa and the Amphibian Man share a creaky ‘60s-style song and dance interlude that comes off more corny than poignant. The Shape of Water doesn’t quite reach the perfection of Pan’s Labyrinth, but silver medal del Toro is most directors’ rhodium. Check it out, even if you’re not a fan of love stories.