“All universal moral principles are idle fancies.” — Marquis de Sade

This is not exactly going to be a shock, but the Marquis de Sade was one strange dude. His very name has come to be a synonym for the love of pain. There are very few men from centuries past who could outrage and scandalize the people of our current ultra-jaded age where violence and pornography are available at the touch of a button. But de Sade was surely one. If you doubt it, take a crack at reading some of his signature works like Justine or 120 Days of Sodom and see how far you get. Breezy beach reads, these are certainly not.

De Sade was more than just a pervert, he was also a moral philosopher and a highly educated guy. At one time he served in the French National Convention following the revolution and had a hand in creating laws. Despite that, he died in an insane asylum in 1814.

The Marquis, whose real name was Donatien Alphonse François, would seem to be an ideal figure to inspire horror films and literature. And indeed, in 1965, de Sade served as the focal point for an exceptional work of horror cinema, one that perhaps he himself would have appreciated.

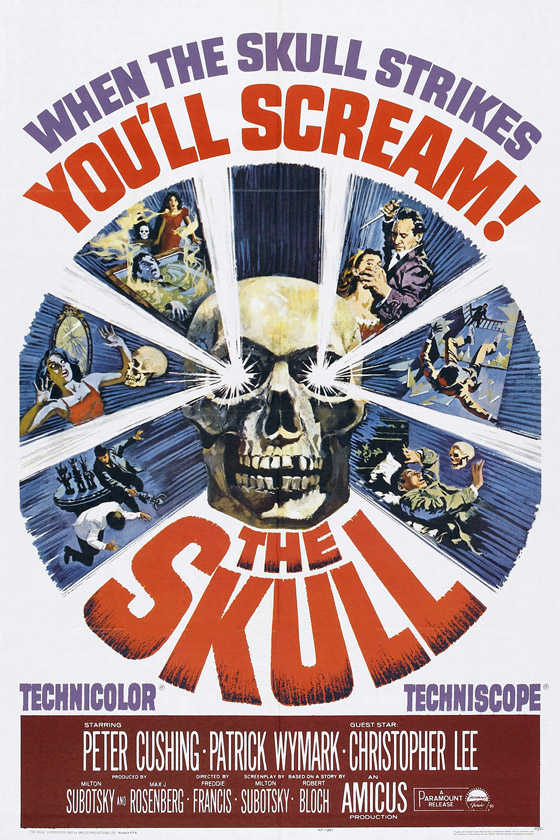

The Skull is a nifty little piece of celluloid that is a perfect storm of various artistic talents coming together. It was a production of Amicus Studio, Hammer’s great rival during the ‘60s and ‘70s and primarily known for their anthology movies. It was based on a story by the infamous Robert Bloch, author of Psycho and many other tales of terror. The cast was dominated by those two titans of British horror, Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, but also featured a phenomenal collection of character actors. Direction was helmed by Freddie Francis, later to become an Oscar winning talent but who cut his teeth on horror movies. Finally, the unique and unnerving musical score was a creation of the avant-garde composer Elisabeth Lutyens. I would defy anyone to find a ‘60s horror film that featured such a cornucopia of creative forces.

Bloch’s original short story was titled “The Skull of the Marquis De Sade”. Bloch toyed with the idea that perhaps the good Marquis was not responsible for his evil thoughts and deeds. What if he was literally demon-possessed and driven by Satanic forces to commit atrocities? What if the power of the demon resided in de Sade’s skull? And what if those who possess the skull become the new receptacle for its evil powers?

The story drew the attention of the ambitious Milton Subotsky, head of Amicus Studios, who was always on the lookout for something that would give him an edge over rival Hammer Studios. He purchased the film rights to the story and put together a team to work on it. And what a team!

For director, he chose the phenomenally talented Freddy Francis, who had already done some great work for Hammer. In the future, he would go on to be the Oscar winning cinematographer of such varied films as Sons and Lovers, Glory, Dune, The Elephant Man, Cape Fear (‘90s remake) and The French Lieutenant’s Woman, among many others. Yet Francis was never ashamed of his earlier low budget horror output and remained a fan of such films until his death in 2007. The Skull would emerge as one of his very best ‘60s films, if not the best.

If you’re going to do a British horror movie in the 1960s, there’s no mystery about who to put on the top of the marquee (not the Marquis!)…Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. The two lifelong friends and costars easily were able to jump from Hammer to Amicus and back again. The Skull was one among many such films for the pair but was a curious outing for them in many ways. Cushing had the lion’s share of the screen time, but a good deal of his part was without dialogue and relied on his physical acting abilities for its impact. Lee had a very low-key role as a kind-hearted collector of occult memorabilia…a rare part in a time when Lee’s roles were overwhelmingly villainous.

Lee and Cushing were no surprise, but Amicus pulled out the stops and loaded The Skull with many of the best British supporting actors, even in small roles. For example, Michael Gough, already well known for his horror work, played the part of the auctioneer here. He probably could have played either Cushing’s or Lee’s characters just as well. That could also be said for the dour Patrick Magee, who appears here as the police coroner. With his somewhat cadaverous looks and richly macabre voice, Magee would have surely been a horror icon if he’d wanted to go that route. Also along for the ride were Nigel Green, Peter Woodthorpe and the excellent Patrick Wymark. Wymark had a pretty meaty part here as the unscrupulous antiquities dealer Anthony Marco.

The last piece of the puzzle was musical director Elisabeth Luytens. She was an eccentric composer who was deeply steeped in the 20th-century avant-garde and no stranger to the world of horror movies. She created the soundtrack to movies such as Never Take Sweets from A Stranger, Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors and The Earth Dies Screaming, among others. For The Skull, she created a subtly nervous and uneasy score that kept the listener in a state of dread, especially the scenes where the skull itself was involved. She was an inspired choice for the film and created a completely different sound than what Hammer’s bombastic “house” composer James Bernard would have come up with.

With so much talent in play, The Skull emerges as a low budget horror movie that punches well beyond its weight class. Let’s take a look at the plot and action of the movie…

The action opens in the early 1800s and what better place to start the story than a spooky, fogbound graveyard in France? Grave robbers are up to no good and have disinterred and opened the coffin of none other than the Marquis De Sade, who makes for a very unpleasant looking corpse. In a harsh scene, the well-to-do Pierre orders that de Sade’s head be removed with the stroke of a spade. Pierre wraps his gruesome prize in sacking and heads back to his Parisian abode.

We see Pierre has got something well worth waiting for there…a curvy and lascivious young woman whom he has obviously dallied with before. But tonight, bedroom games will have to wait. Pierre sets about removing all flesh and tissue from de Sade’s skull with an acid bath. When the girl hears nothing from Pierre, she forces her way into his work chamber…and screams in horror when his body rises from the steaming bath. Next to her, the skull leers ghoulishly.

This is a good place to mention that in real life the actual remains of de Sade were stolen and never recovered. He left very strict instructions on how and where his body was to be buried…instructions which were never carried out. It is believed that his skull was stolen by a band of phrenologists…men who believed they could predict behavior by the shape of a person’s head. Phrenology was quite the fad in the 1800s and indeed, Pierre is described as a phrenologist in the script. So, in this case, the movie follows real life. I certainly hope the real skull didn’t act up like the one in the movie!

We move to the 1960s, where the wealthy collector Christopher Maitland (Peter Cushing) is attending an auction of unwholesome occult objects. He gets in a bidding war with his friendly rival Sir Matthew Phillips (Christopher Lee) over a set of demonic statues. Phillips wins the battle with a huge bid that is more than the statues are actually worth. Maitland is intrigued by Phillips’ obsessive behavior regarding the statues.

Later, Maitland is paid a visit at his luxurious apartment by Anthony Marco (Patrick Wymark), an unsavory dealer in occult rarities whom he has had dealings with before. Marco has two items of great interest to offer: a grotesque book that is bound in human flesh and a grinning skull that Marco claims belongs to de Sade himself. Maitland is skeptical about the skull but is already becoming fascinated by it….

I have to mention here how wonderful Maitland’s apartment is and how beautifully Freddie Francis and his cinematographer John Wilcox film it. The apartment is filled to the brim with wonderful and very authentic looking occult rarities and trinkets. The camera in this movie is obsessed with evil objects and every shot seems composed to lovingly focus on statues of gargoyles, odd paintings, ancient books and esoteric machines. The film is a pleasure to look at.

Maitland does research on Marco’s objects and also rustles up the considerable sum necessary to purchase them. He learns more of the history of de Sade’s skull and the movie segues to a scene back in Paris of the 1800s, immediately following the death of Pierre the phrenologist. It doesn’t take long for the skull’s malevolent influence to assert itself. Mild-mannered Dr. Londe (George Coulouris), an associate of Pierre’s, brutally stabs Pierre’s female friend to death.

There’s also a great dream sequence where Maitland imagines he has been virtually kidnapped by two thuggish “policemen” who seem to have no respect for the law. These corrupt gendarmes escort Maitland to a strange location where he is brought before a judge in full English regalia. The judge sentences Maitland to play a round of Russian roulette with a pistol, which the terrified man does until with a bang he wakens from the dreadful nightmare. This whole scene is a surreal, Kafka-eseque ordeal that is one of the best sequences in the film. The power of the skull is already beginning to warp Maitland’s mind…

Maitland pays a visit to his friend Sir Matthew and plays a sociable game of snooker with him while trying to find out more about the skull and the book. Phillips’ abode is another terrific example of upper-class British décor with a diabolical touch. Phillips confirms that both skull and book are absolutely authentic. When Maitland asks how he knows, Sir Matthew informs him that both items belonged to him before Marco stole them. He further says that he is glad both items are no longer his because they had been causing him to think unhealthy thoughts. He begs Maitland to get rid of the skull and speculates that it may contain the spirit of the demon Baalberith, one of the four demonic figures he bought at the auction. Baalberith is a spirit known for causing murder.

It is already becoming too late for Maitland. He breaks down and buys the items, using money he really doesn’t have. Before long, murder erupts and the police are involved. Maitland’s wife notices the change in her husband but cannot wrench him away from the skull.

In the last third of the movie, there is little to no dialogue as Maitland finds himself descending further into madness. The skull seems able to float through the air and pursue him. These scenes are super memorable because they are shot from within the skull and seem to be from the skull’s point of view. Maitland and the skull are now in a death duel for control of his mind.

In addition to the “Skull-O-Vision,” we also get a lot of shots of the skull floating in air and flying after Maitland. One unfortunate thing that almost every critic went out of their way to mention is that if you look hard, you can see wires holding the skull up during the flying scenes. I think that in days gone by viewers would be so into the movie by this point that they would be unlikely to notice. But in this day and age, people live to nitpick and so The Skull has become the movie with the skull on wires.

In the movie’s climactic wordless scenes, everything has the feverish feeling of a drug-induced nightmare. The ending is predictable, but Cushing is so great in scenes that require only physical acting and the direction of Francis is so sure that the viewer is propelled along to inevitable doom with a sure hand. The score of Elisabeth Luytens also needs to be appreciated … the creepy, almost minimalist score provides perfect accompaniment.

When the movie was released in France, the descendants of Marquis de Sade strongly opposed the movie using the title The Skull of de Sade, resulting in the movie hastily being retitled The Evil Skull there. In England and America, it was simply The Skull.

The film certainly did not break any box office records, but it did attract the attention of horror fans with its unique direction and musical score (look out for the skylight scene for another example of great cinematography). And over time, it has gathered quite a bit of favorable opinion. Some consider it Amicus’ best directed film, which is saying something considering that the studio put out the highly regarded Tales from The Crypt, also directed by Francis.

The movie remains a favorite of classic horror fans. If you should ever happen to see a grinning cranium arrive without explanation on your doorstep, RUN, don’t walk, as far as you can!!!