Author Harlan Ellison died in his sleep on June 28th at the age of 84. I’ve written and deleted that sentence about two-hundred times over the past 48 hours. I have no idea what to follow it with, because I have no idea how to sum him up. There’s no clever literary trick to summarize Harlan Ellison. You can’t carve out a neat little three-paragraph obit from a life as grand and messy and elemental as his. It’s like trying to sum up the Pacific Ocean by saying how many cups of water it contains. So I’m left with that basic fact: Two days ago, Harlan Ellison died. What happens next, for me, is time travel.

It’s 2000, and I’ve just moved from suburban Baltimore to small-town Iowa. I’m a tightly-wound, neurotic, rigidly well-behaved kid bubbling over with an anger so hot and violent and all-encompassing that I’m barely conscious of it, like the proverbial frog in boiling water. I want to be a writer but I forgot what it is to enjoy writing; I write to impress English teachers and my parents with my bon mots and silly, pretentious attempts to be a Great Writer as a high school senior. I hate high school, I hate Iowa, and I hate this art that I’m supposed to love, that I’ve already begun to stake my life’s worth on, that I can’t bring myself to walk away from.

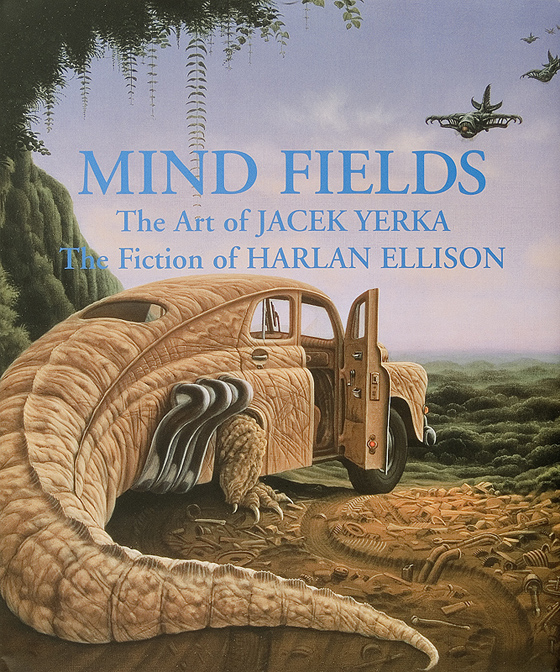

Somewhere in this maelstrom, a teacher asks me if I’ve ever read somebody named Harlan Ellison. I tell him I haven’t. He lends me a science-fiction anthology with a story called “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” in it. I finish that, and he lends me a book called Mind Fields, which pairs this Harlan Ellison’s flash fiction with beautiful paintings by the Polish surrealist Jacek Yerka. Then I read everything by him I can get my hands on, because what I’ve found isn’t just a good writer, but something like a trash-talking bodhisattva. He shows me the way out. I fall in love with words again. He’s my Virgil, leading me through a corn-choked circle of hell.

Ellison bristled at being called a horror writer, insisting that he wrote “fiction of the macabre.” Whatever. Fuck it. What matters more than labels is the stories so weird and deep and original that even now, nobody’s quite managed to imitate them. “The Prowler on the City at the Edge of the World” sends Jack the Ripper into the distant future. The innocently-titled “A Boy and His Dog” pairs a post-apocalyptic thug with a telepathic dog in a twisted adventure that somehow manages to be both touching and horrifying. “The Deathbird” is a Gnostic fantasy which proposes that the Serpent was the real hero of the Book of Genesis, but God had better PR. “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” is pure nightmare, the story of the last six human beings in existence, kept alive for centuries just so an omnipotent supercomputer can torture them.

The truth is, Ellison wasn’t a horror writer—not just a horror writer, at least. He did science fiction. He did realism. He did comedy. He did memoirs and essays so entertaining that I came to love them as much as I loved his stories. He did investigative reporting, going undercover to run with a street gang in New York City.

He wasn’t an easy man to get along with, by all accounts. His list of enemies included everyone from Roy Disney (who fired him for joking about making a porn film starring Minnie Mouse) to Barbara Streisand (with whom he evidently performed when Babs was young) to William Shatner and Gene Roddenberry. Through the sandpaper alchemy of his personality, he transmuted friends into lifelong enemies. He raged against meaningless classifications: science-fiction is a noble genre, but “sci-fi” is hackwork, with a name that “sounds like crickets fucking.” He hated TV and computers and video games on principle. Let’s be honest—he was an asshole.

But he was usually an asshole for all the right reasons, a volcano of selfless self-righteousness whose sympathies unfailingly rested with the downtrodden and the voiceless. He marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma and came out as a strong, early voice for women’s lib. His work exudes foul-mouthed, pugnacious, sincere humanity. His rage spoke to my rage, as his bravery spoke to the bravery I wanted to manifest and his prose spoke to the prose I wish I could write.

I hadn’t thought much about Harlan Ellison for a number of years. I haven’t read anything by him since my early twenties, and since the 2000s he seems to have more or less coasted on his reputation. His health grew worse: a heart attack in 1994 and a stroke in 2014. In the increasingly priggish world of modern speculative fiction, he was like a prehistoric monster, a bloody-jawed and majestic thing we all knew would die out, but that improved the world with its wrathful existence anyhow. And then, on June 28th, 2018, author Harlan Ellison died in his sleep at the age of 84.

I never met him, and he probably wouldn’t have liked me if I had. I regret it anyway. I wish I could have shaken his hand, told him what he meant to me, and basked for a few minutes in the atomic glow of his rabid genius.

Goodbye, Mr. Ellison. May your memory be a haunting and inescapable blessing.