When it comes to spooky tales of witchcraft and deviltry, Russia and surrounding countries like Ukraine and Belarus should never be overlooked. The old Slavic myths that saturate these countries are brimming with stories of ghosts, forest demons and cannibal witches but are not that well-known here in the West. Well, with me being a multicultural sort of ghoul, I plan to correct some of this oversight and focus upon an especially frightening Russian witch story that was made into a quite amazing movie.

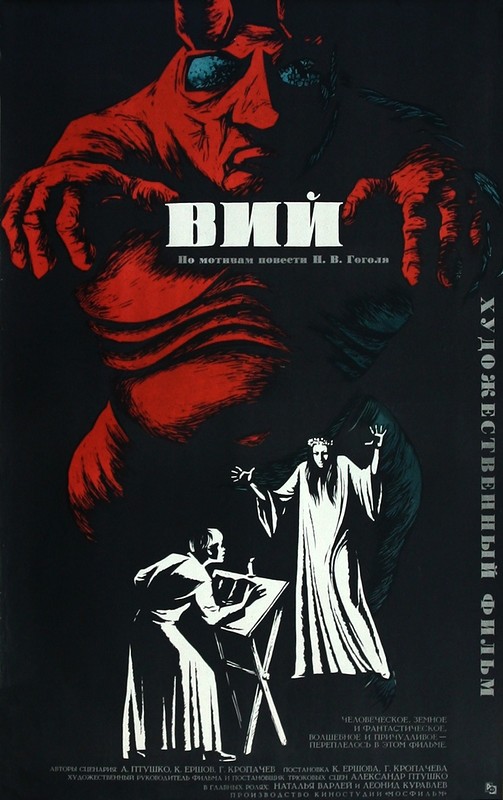

Viy was a novella written in the early 19th century by the celebrated Russian writer Nikolai Gogol. Gogol based the supposedly “true” story upon Ukrainian myths and folklore. “Viy” is a word that means “evil Spirit” in the old Ukrainian tongue. The story was first published in a collection of Gogol’s tales Mirgorod and was easily the most popular of the anthology’s stories. In basic form, it told the story of a young seminary student who is paid a fortune to recite prayers over a dead girl suspected of witchcraft. He must recite the prayers on three consecutive nights, lasting until the sun comes up. He is tormented by the spirit of the dead girl and the demons she summons, the chief of which is the monstrous Viy.

One would think that such an old-fashioned tale would be among the last to be filmed by Soviet filmmakers during the heart of Russia’s communist period. Old myths and ghost stories die hard, though and even the specter of Old Stalin couldn’t keep Gogol’s story from being made into a movie in 1967. The movie Viy was jointly directed by Konstantin Yershov and Georgi Kropachyov. When I saw a brief clip of it used for a video of the Bathory song “Woman of Dark Desires,” I was blown away and knew I had to see this oddity of Russian folk horror.

It’s always a treat to see a movie from an unexpected corner of the world. One becomes so used to the typical Western films that something featuring unfamiliar faces and using unfamiliar locations is a welcome novelty. So it was with the film version of Viy. The movie conjures up the feeling of medieval peasant life in the Ukraine that you feel almost like you have traveled in time. Since none of the stars are recognizable, you see them strictly as the characters they play. This really adds to the experience.

Another strong aspect of Viy are the clever practical effects. No CGI here….the witches and demons are real and physical, including the monstrous Viy itself. The flying sequences are smartly done and very convincing. Lighting and sound are also utilized to maximum effect. In every way, Viy is an immersive experience that really does seem to be a Russian folk tale come to life.

What of Gogol’s tale? Well, let’s look more closely at the simple but effective story…

We begin at a stern Eastern Orthodox seminary where young men learn the ways of God. Some have a harder time with Godliness than others. That’s where our hero Khoma and his two young friends come in. The time has come for a brief vacation from the severe conditions of the seminary, but young Khoma and friends are on the abbot’s watch list due to horseplay and love of vodka. He gives them a stern warning and tells them to leave their rowdy ways behind when they return. The boys are chastened but their piety doesn’t last long. The three proceed to tie one on and carouse through the rural countryside in the dead of the night.

Drunk and lost, they wind up at a lone farmhouse where they beg the old hag who lives there to stay in her barn for the night. She agrees on the condition that each of them must sleep in a different part of the farm than the others. They agree and Khoma winds up in the horse barn. It is not long before the old woman pays him a visit and blatantly tries to seduce him. Horrified by the old hag, Khoma attempts to flee but the old woman jumps on his back and tightly embraces him, cackling as he runs across the countryside. To the young man’s horror, he finds himself flying through the air with the old woman still clinging to him. The woman is a witch and is riding him like a broom!

Khoma pretends to agree to her advances, but as soon as he is back upon the ground, he grabs a stout branch and furiously beats her. The witch collapses and says she is dying. As she breathes her last, she is transformed into a beautiful girl. Terrified beyond reason, Khoma runs all the way back to the seminary, where he collapses in exhaustion.

When he awakens, he is summoned immediately by the abbot, who seems to know of his adventures. The abbot orders Khoma to travel to a remote village where he must read prayers for the dying daughter of a rich merchant. If he refuses, he will be beaten and expelled from the seminary. The dying girl asked for Khoma to attend to her by name, but how she knew of him is a mystery.

A reluctant Khoma accompanies a band of rough and drunken Cossacks to the village, where Khoma meets the rich merchant. He is already too late…the girl has died. The merchant then demands that Khoma spend three consecutive nights reading prayers over her body in the local church. He must read from sundown to when the rooster crows in the morning and he will be by himself. Cossacks will be watching the building to make sure he stays inside. If Khoma completes the assignment, he will be richly rewarded. But if he fails, his punishment will be severe.

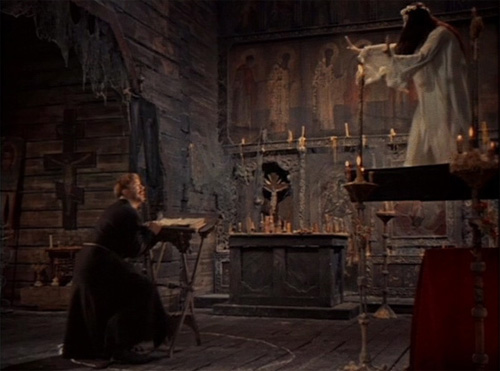

Reserved to his fate, Khoma agrees and spends the next day drinking with the Cossacks to work up his courage. As twilight nears, he is led into the cavernous church, where the pale and beautiful body of the dead girl lies in an open casket. The doors are locked and closed behind him…he is alone with the body until dawn.

The atmosphere of the movie now intensifies to a fever pitch. The church and the village are absolutely authentic in their portrayal…it’s like we are looking through a window into a medieval age. Cats run yowling across the floor of the church….in a dusty corner, birds screech and crow. The crudely painted faces of saints watch as Khoma nervously lights candles. He begins to read prayers…

Suddenly the eyes of the dead girl snap open. Still dressed in her white burial shroud, she sits up in her coffin. Khoma is overcome with horror. The revenant stiffly gets out of her coffin and shuffles forward. Khoma notices despite his terror that she seems to be blind as she gropes forward in an attempt to find him. The young priest remembers his training and uses a piece of chalk to draw a sacred circle around the lectern where the bible is located. The desperate gamble works…an invisible field of force now protects him from the dead girl’s clutching hands.

Here I have to comment on the dark and spectral beauty of Natalya Varley as the living dead girl. With her raven dark hair and intense eyes, she’s every Goth guy’s dream. Her stiff movements, which gradually loosen the more she is awake, are striking. Natalya really steals the show as the creepy witch from beyond the grave.

Khoma now babbles prayers with the intensity of a man confronting the damned. The dead girl continues to try and find a break in the field which surrounds the young priest but is unable to do so. For the rest of the night, Khoma continues to read psalms and trust in the magic circle to protect him. Finally, the cock crows. Dawn has arrived. With robotic suddenness, the girl returns to her coffin and resumes the sleep of death. But this is just the first night…

Khoma spends most of the next day drinking furiously to keep from running away. Evening approaches and he is again escorted to the church and locked in. The second night begins. Wasting no time, he immediately draws a sacred circle around the lectern to protect him.

That proves to be very prudent, as the witch again rises from her coffin and again blindly gropes for the terrified young man. This time, though, the coffin itself levitates and floats in the air. Standing astride the coffin almost like it was a surfboard, the dead girl flies around the inside of the church and aims the coffin to ram against the mystical forcefield protecting Khoma. The photography and effects work in this sequence is frankly fantastic. And also very disorienting for the viewer.

Khoma frantically continues to read prayers inside the circle even as the coffin bangs relentlessly against the protective barrier. The girl seems stronger than the previous night and less stiff. After a harrowing, sleepless night, the cock crows again, but as the girl returns to her coffin, she speaks for the first time and curses Khoma to go blind and have his hair turn white.

The experience seems to have warped Khoma’s mind. He can still see but his hair has indeed turned white. He drinks heavily, plays a flute and dances clumsily in front of the bemused villagers. But he finally begs to see the merchant. He pleads to be released from his duties, but the merchant does not relent. He swears that Khoma will be lashed a thousand times if he runs away. Despite that threat, Khoma does indeed try to flee the village but is captured by the Cossacks.

He is locked in the church for the final night. Khoma wastes no time drawing the sacred circle and this again proves to be a wise precaution, as the dead girl swiftly rises from her coffin. Tonight she is no longer blind and seems much more energetic and less stiff than before. She tells the trembling Khoma that tonight she will summon up the demons of hell to destroy him.

If you ever saw the ‘70s occult film The Sentinel, you’ll remember at the end when the devilish Burgess Meredith called up an army of freaks from the underworld to help his cause. That scene is quite similar to what appears now in Viy. A demonic platoon of dancing skeletons, sinister imps and grotesque gargoyles materializes out of the very walls of the church to throw themselves at the invisible field of protection surrounding Khoma. Much like in The Sentinel, real dwarves and people with deformities are used to portray the fiends, which makes the scene all the more disturbing. The makeup on these monsters is top notch and matches the best of anything coming out of Hollywood in the same period.

With the undead witch muttering and laughing, the demons try to break through to Khoma. But the shield stands strong and the young student continues to read his prayers. Frustrated, the witch now summons up VIY…one of the mightiest of the evil spirits. Just the mention of his name causes the other demons to cringe. Soon Viy lumbers into sight…a massive monster with huge drooping eyelids.

The witch gloats and tells Khoma that when Viy’s eyelids are opened and he turns his gaze upon Khoma, he will be made helpless. The monsters do manage to open Viy’s eyes and the archdemon’s glowing gaze is turned upon his prey…

The rest you will have to find out for yourself. Suffice to say, the ending to the film is rather ambiguous and can support a number of interpretations. I managed to find a whole uncut version on Youtube.

Viy takes a while to get going in the beginning, but the feel of authenticity regarding the medieval Ukrainian setting really sucks you in. The buildings, the clothing, even the very appearance of the actors seem to be right out of the period. There’s no Hollywood polish or pageantry. The village where Khoma performs his exorcisms really does look like a dumpy Dark Ages village.

When Khoma is locked inside the church, Viy begins to take off. It’s a masterpiece of sound, lighting and mood, spiced with some visually arresting affects. Squawking birds and squealing cats seem to play a heavy symbolic role in the proceedings. And the cadaverous beauty of Natalya Varley is also striking. I got the impression that the spirit of the old hag Khoma beat to death may have taken possession of the merchant’s daughter just before her death and made a request for Khoma to read prayers as part of a sinister plot of sorcerous revenge. There’s also a possibility that the hag and the girl may have been in the same coven.

I am still amazed that a picture that revolves so much around religious imagery was produced by the Soviet state film company. If there is any communist or socialist propaganda in Viy, it’s buried too deep for me to detect. Sometimes, a good ghost story is just a good ghost story, no matter which society or culture is producing it.

I understand that another version of Viy was filmed in 2014 but since I haven’t seen it, I can’t comment on it. It would have to go quite a way to surpass the macabre charm of the 1967 offering. If you are interested in a demonic tale from an unlikely source and without any of the familiar actors or trappings of Western film, I urge you to seek out this version of Viy.