I tried to build a golem. I was in fifth grade and I had read way too much Dungeons & Dragons and heard the Judah Lowe story.[1] My sister and I were bored and we had some modeling clay. The confluence of all these factors made me think, “You know, this probably won’t work, but how awesome would it be if it did?”

I use the term golem, of course, as a stand-in for any kind of fantasy automaton. The word literally means “clump of earth” in Hebrew, and classically the golem is a man made from clay and animated through the inscription of the term emet (“life”) on his forehead. Traditional stories revolve around the golem as either a protector of the Jews (like Lowe’s guardian) or a warning against lightly taking up powers rightly reserved only for God (rabbi animates golem, golem goes crazy, rabbi has to scratch a letter off the golem’s forehead so it says met [“dead”] and deanimates). In modern interpretations (as China Mieville pointed out in an interview) the golem concept has expanded to include everything from Frankensteinian monsters to steam-powered robots. Anything that can’t justifiably be called a replicant, a cyborg, or a droid gets lumped under the category “golem.”

Kabbalistically, of course (the real kind, not the Madonna kind), the fact that a golem is made from clay is important. In the Bible, God forms Adam from earth, so the creation of a golem is a mortal attempt to attain Godly nature. Jewish folklore provided for different types of created life: one story has the philosopher Maimonides creating a homunculus from the body parts of an apprentice. But these weren’t golems. I think Mieville is quite right when he states that we owe the concept of golems made from different materials to none other than Dungeons & Dragons.

D&D took the concept of the clay man and expanded it radically. In various sources, the game depicts golems made of flesh, iron, stone, wood, straw, gelatin, blood, dolls, bones, brains, coral, sand, obsidian, salt, maggots, snow, wax, mist, hangman’s nooses, and zombie parts.[2] The golem became a genus of monsters, some unmistakably associated with evil rather than just the powerful but plodding and sometimes uncontrollable creature depicted in the original Jewish stories. This was an intriguing development with wide implications, which I’ll discuss momentarily.

But my sister and I didn’t have hangman’s nooses or obsidian; we had Play-Doh. Reasoning that we should probably start small and work our way up, we made a little humanoid figure about the height of an action figure. If a six-inch Play-Doh homunculus proved a tractable servant, we could then move on to creating bigger and bigger golems with the ultimate aim of crafting something like a Sumerian battle mech. There were some problems, though. I didn’t speak or write any Hebrew aside from a prayer thanking God for bread, which would probably win me divine bonus points, but no golem. Clearly, I had to improvise.

At that point, I had a pet lizard that ate crickets. The crickets lived their brief lives in a stinking terrarium with a dried-out apple core for food. Thinking quickly, I reasoned that maybe if I mashed up some crickets and put them in the hollowed-out “brain cavity” of the golem, the “transfer of life force” might do what the total lack of spirituality and rabbinic learning couldn’t. I mixed in some cloves, mustard, and pepper for good measure and waited with my sister to see what would happen. After a good ten minutes of our golem showing absolutely no sign of animation, it hit home that I was not going to be the next Judah Lowe, and moreover that I had just wasted a can of Play-Doh by smearing it full of mashed crickets. Yet another corner of childhood wonder dog-eared into adult disillusion.

But I love golems. I love the fact that since their advent as a part of nerd culture (arguably going back to the silent German Expressionist movie Der Golem), the definition of golem has expanded to include any magically-animated artificial creature, from the laser-shooting robots in Final Fantasy games to the hysterically vast list of D&D “constructs.” To me, this isn’t an offense or a theft, but a neat permutation on an already neat idea. It appeals to my sense of the cross-cultural. Doesn’t it stand to reason that if rabbis make golems out of clay then Aztec priests might build them out of flint or obsidian, and Viking seidr women might carve them from driftwood and engrave runes on their brows, and Aboriginal shamans might animate human-like figures from swarms of honeypot ants or funnelweb spiders? To me, this is awesome stuff. I like the fact that people were intrigued enough by the idea of golems to take the idea and run with it. Calling something a golem gifts it with a mystic and mysterious atmosphere that “robot,” “automaton,” “artificial man,” etc., don’t carry.

Writer Pam Noles, in the wake of the SyFy channel’s (by all accounts atrocious) adaptation of Ursula Le Guin’s classic A Wizard of Earthsea wrote an excellent essay entitled “Shame” that dissects the experience of being a black speculative fiction fan, and particularly the ultimate meaninglessness of attempting to find a correlation between race and culture in this global earth on which we live. Noles concludes ultimately that in this world of white rap listeners, black manga fans and Asian classical pianists, trying to parse out culture and ethnicity as a packaged entity is limiting and non-applicable. I approach all this not as a partisan or academician, but instead as a writer and a fan. Charles Saunders’s Imaro stories weren’t just great because they took the whole Conan idea and applied it to a Maasai warrior in a world based off Africa, but because this was new territory, utterly unmined. New monsters (Isikukumdevu, the water demon, stands out in particular), new worlds, new stories.

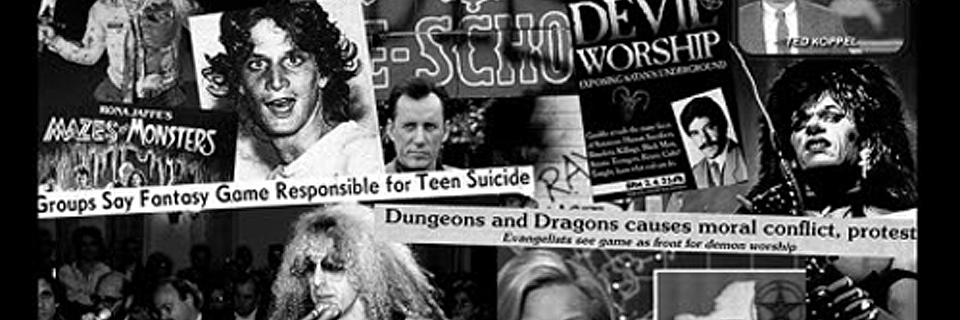

Speculative fiction—yes, even horror, for all its vaunted pushing of the envelope—has often enough been a pretty staid, conservative set of genres; all those cheesy pulp stories about Voodoo witch doctors[3] and Indian burial grounds, the innumerable “good girls live, sluts die” slasher films. But horror and other fantastic genres can also serve to bridge worlds of difference far vaster than skin color or ethnicity. I guess you could accuse me, half-Jewish, agnostic, and growing up under circumstances generally tolerant to both, of not being able to speak to the deep hurt that a real Jew would feel to see an idea as sacred as that of the golem violated by crass game designers. But as a member of one of the first widely intermarried generations of Jews, these new golems hold a special freight–part Hebrew and part something else. If ethnicity is still the rigid division it was in the past, where do I fall? Where, indeed, do most of us, constructed golems of international genes that we increasingly are? If experience is a teacher, I’ll probably have to smash some more crickets to find out.

[1] Judah Lowe was a legendary rabbi from sixteenth century Prague who created a golem to defend the city’s Jewish Quarter from anti-Semitic riots.

[2] Not just any body parts—that would be a flesh golem. These had to come from zombies.

[3] Fun fact: the journalist who gave us most of our ideas about what voodoo looks like—pins in dolls and all that—actually knew nothing about it. In the beginning of the twentieth century, there were few sources on actual Voodoo practice, so he took European ideas of witchcraft and transplanted them into the Caribbean. This is a shame not only because it’s ignorant, sloppy, and racist, but because actual Voodoo lore is awesomely poetic and picturesque: cults of bokors (witches) turning into python-men and elephant-men (all under the general rubric of “werewolf”), zombies who realize only when they taste salt that they’re actually dead, black Sabbaths of toxic plants in the jungles at midnight—these stories Voodoo pracitioners tell are far cooler than any of the stories we’ve made up about them.