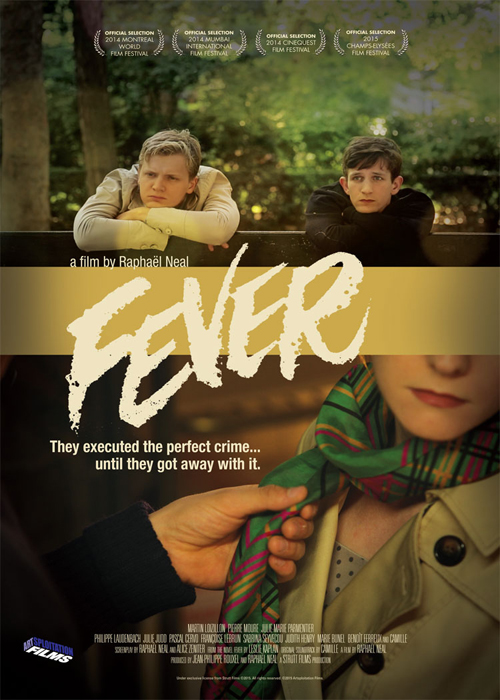

Raphael Neal, the French actor turned auteur, shows admirable restraint and grace with Fever, his film festival darling loosely based on the Leopold and Loeb murder that resulted in a fascinating trial that captivated America in the 1920s.

As with that crime, two well-to-do students commit a murder for nothing more than the thrill of the kill. Unlike that crime and the resulting books and movies that documented it, Fever focuses on a psychological exploration of the murderers. There is no motivation, there is no trial, there is no punishment per se. But that’s not to say there are no consequences.

The film opens dark – no visuals, just a black screen and muffled noises. Then we follow the two students, Damien and Pierre (Martin Loisillon and Pierre Moure) down a set of stairs and onto the street. Pierre bumps into a pedestrian, Zoe (Julie-Marie Parmentier), and drops a glove as they run from the scene. Only later does she begin to suspect the significance of her encounter.

It’s a bloodless crime. A woman was strangled. A police investigation ensues. But viewers move quickly into the teens’ lives – at home, in school, with classmates, and alone together. If you’re looking for scares and gore, you won’t find it here.

What you will find is a suspenseful portrait of our three main characters.

Spurred in part by discussions in a philosophy class and also as a means to tamp down their guilt, Damien and Pierre throw themselves into the study of Nazi Germany’s “Final Solution” and the rationalizations of Maurice Papon, Adolf Eichmann, and others for their roles in the Holocaust.

We also get a glimpse into their home lives which yields possible impetuses in their actions – an Oedipus complex here, stunted maturity there, etc. Director Neal wisely leaves those open to interpretation.

For her part, Zoe, an optician who works in the same neighborhood where the murder occurred, struggles with her suspicions and with her mundane life. She’s been in an unfulfilling relationship for 12 years but doesn’t have an incentive for change. She is, however, intrigued by the murder and the murderers and begins to look for them. It culminates in a grocery store when she sees Damien and Pierre, who attempt to elude her. When she finally finds herself face to face with Damien, she simply returns the glove.

Why not contact the police? Why divorce herself from suspicion? Why ignore the satisfaction of punishing the crime?

We’re left to our own guess as to why, but for whatever reason, Zoe begins to make changes in her life.

More significantly, in a subsequent philosophy classroom scene, a discussion causes Pierre to begin crying uncontrollably, consoled only by Damien. The two are on the verge of a confession, but the teacher mistakes their emotional deluge as stress over an upcoming examination and nothing comes of it.

So, they got away with it? It might seem so, but perhaps we’re merely witness to the years and decades of torment to come.

The performances in Fever are uniformly good, particularly Loisillon as Damien. He waffles chillingly between stoicism and exuberance. Released originally in 2014, the film, which is subtitled, was well received at several festivals, and deservedly so. The North American rights to Fever were acquired by Artsploitation Films, so it’s making the rounds again and deserves an audience.

One final observation: The soundtrack features a performance of the song “Fever,” made famous years ago by Peggy Lee. Here it’s performed by French singer Camille, and the rendition is at once sexy and haunting, worthy of an iTunes search. In keeping with the film, it may not give you fever, but it’ll ratchet up the thermostat a degree or two.